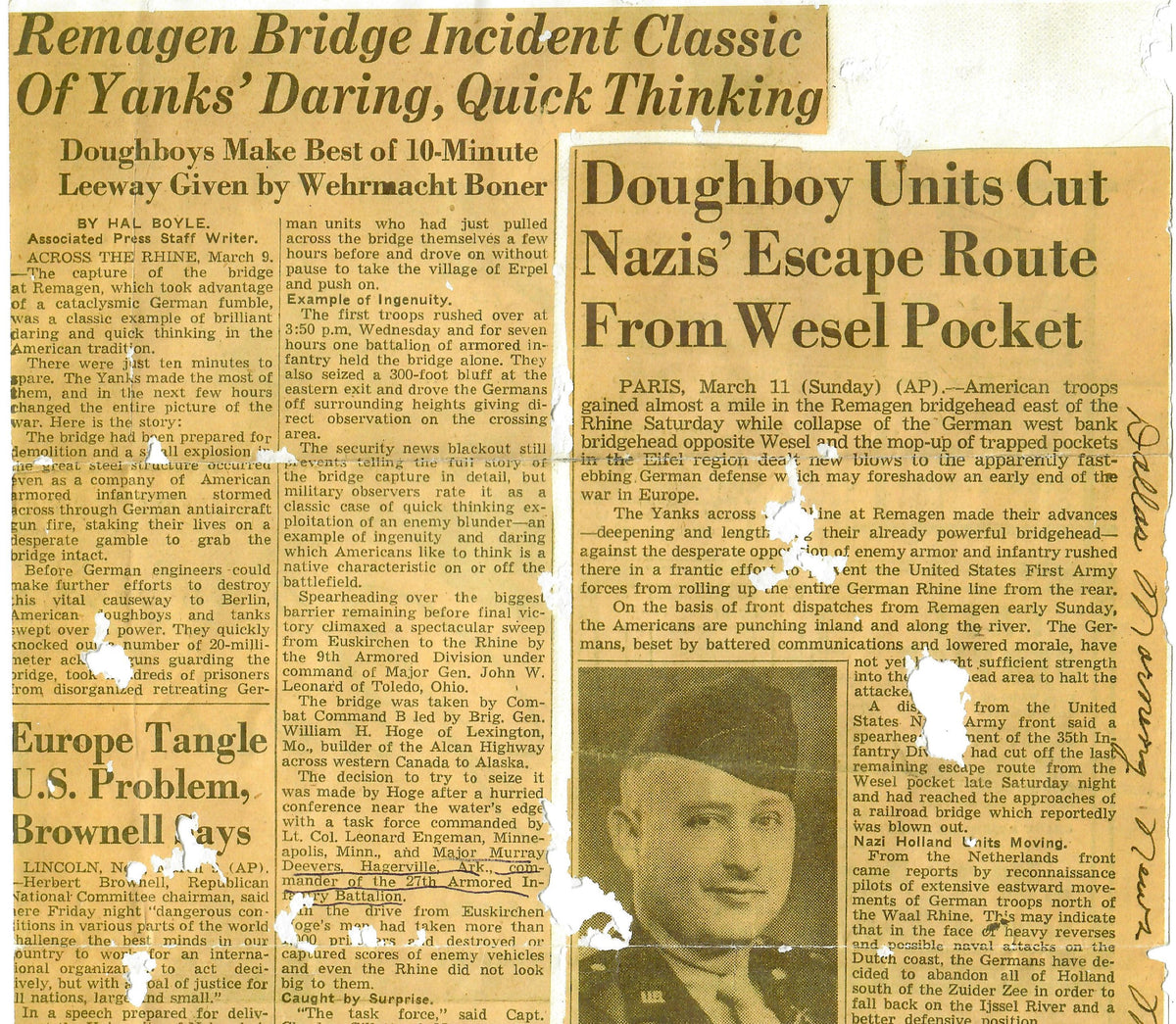

Original German WWII Luftwaffe Fallschirmjäger Paratrooper RZ20 Camouflage Parachute Brought Home by U.S. 27th AIB Commander Major Murray Deevers – Battle of Remagen Original Items

$ 1.295,00 $ 323,75

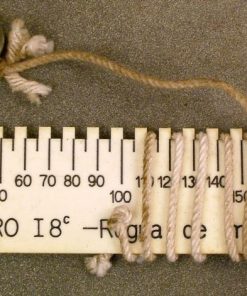

Original Item: Only One Available. This is a totally original German WWII Rz20 Paratrooper parachute that includes a 28 panel camouflage silk canopy. This is kept inside an original canopy bag which was sent home from Europe during or directly after WWII.

The silk canopy is still packed and we do not want to unpack it to inspect any stampings present. Overall condition is very good but unfortunately the harness was removed, leaving only the canvas bag.

The parachute was brought or sent home by the 27th Armored Infantry Battalion Commander, Major John Murray Deevers. Murray was born August 28, 1909 in Arkansas, a son of William Fred Deevers (1876-1953) and Floy Murray Deevers (1882-1961). He was married to Wilma Bartley Deevers (1911-1992). His siblings were Charles Deevers (1900-1961), L.E. Devers (1903-1978), and Sallie Deevers Henderson (Mrs. Ertle Ray Henderson 1906-1988). Lt. Colonel Deevers was the commander of the 27th Armored Infantry Battalion that participated in the capture of the Bridge of Remagen during World War II. In his local community of Pocahontas, Mississippi, he was a scout master.

Murray Deevers served in the United States Army during WWII and the Korean War up until his untimely death in 1954 while flying over Japan.

On February 1, 1954, a US Air Force Curtiss C-46D-15-CU Commando (tail number 44-78027) had an in-flight fire in the main cabin while flying over Japan. Thirty minutes prior to that it had taken off at Misawa AFB. The pilot tried to ditch the aircraft in the Tsugaru Strait between Honshu and Hokkaido. He lost control of the plane and it crashed into the sea, killing all 35 onboard. After reporting the fire in the cargo hold and that a ditching was imminent, the last message from the aircraft was, “I’ve lost control of the aircraft. We’re going in.” The plane crashed 30 km south of Tomakomai. Japanese on a nearby shore said that they saw the plane’s distress signal and some open parachutes as the aircraft lost altitude.

According to an Air Force spokesman, some open parachutes and an oil slick were spotted by search planes, but a big blizzard had hit Hokkaido just a couple of days before and the water was very cold. There was also light snow. The spokesman said that a man could stay alive only a few minutes in the frigid water. The disaster occurred in a very short time, and reports stated that the occupants were probably trapped in the aircraft, thus preventing escape.

Five crew members were missing in action, twenty-eight passengers were missing in action, and two passengers’ bodies were recovered. Then a Lieutenant Colonel, John Murray Deevers, was one of the 28 passengers that went missing in action and declared dead. He was serving with the 1st Cavalry Division at the time.

This is a wonderful and Genuine WWII German Paratroopers’ Parachute Canopy and comes with a copy of a newspaper article from 1945. The article features Murray Deevers and talks about the battle of Remagen Bridge. A wonderful item that comes ready to display!

Battle of Remagen

On the afternoon of 7 March 1945, Lt. Col. Leonard Engemann led Task Force Engemann towards Remagen, a small village of about 5,000 residents on the Rhine with the objective of capturing the town. The task force, part of Combat Command B, consisted of C Troop of the 89th Reconnaissance Squadron manning M8 Light Armored Cars and M3 Half-tracks; Company A of 27th Armored Infantry Battalion (27th AIB) equipped with M3 Half-tracks, commanded by Major Murray Deevers; one platoon of Company B, 9th Armored Engineer Battalion (9th AEB) led by Lt. Hugh Mott; and three companies of the 14th Tank Battalion (14th TB): Company A (led by 22-year-old Lt. Karl H. Timmermann); Company B (led by Lt. Jack Liedke); and Company C (led by Lt. William E. McMaster).

The three tank companies of the 14th TB each consisted of three platoons. 1st Platoon of Company A, 14th TB, led by Lt. John Grimball, had been assigned five of the newest heavy-duty T26E3 Pershing tanks, although only four were operational on 7 March. The other platoons were each equipped with five M4A3 Sherman tanks, and the company also had a command unit of three more Sherman tanks. Their orders were to capture the town of Remagen, and then continue south to link up with Patton’s Third Army, but were not given any specific instructions regarding the Ludendorff Bridge.

At 12:56, scouts from 89th Reconnaissance Squadron arrived on a hill on the north side of Remagen overlooking the village and were astonished to see that the Ludendorff Bridge was still standing. It was one of three remaining bridges across the Rhine that the Germans had not yet blown up in advance of the Allied armies’ advance. Lt. Timmermann and Grimball followed the scouts on the rise to see for themselves and radioed the surprising news to Task Force Commander Engemann. Arriving on the rise, Engemann could see retreating German vehicles and forces filling Remagen’s streets, all heading over the bridge, which was full of soldiers, civilians, vehicles and even livestock. Previous attacks by Allied aircraft had destroyed the vessels used to ferry civilians and workers across the Rhine. All were now forced to use the bridge.

Captain Bratge was in Remagen on the western approach to the bridge directing traffic onto the bridge. Timmermann called for artillery to fire on the bridge using proximity fuses to slow down the German retreat, but the artillery commander refused because he could not be sure that U.S. troops would not be hit by the shells.

When Operations Officer of Combat Command B Maj. Ben Cothran arrived and saw that the bridge was still standing, he radioed Brig. General William M. Hoge, commanding officer of the Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division. Hoge joined them as quickly as he could. Engemann was cautiously considering his options when Hoge ordered him to immediately move into town and to capture the bridge as quickly as possible.

Timmermann had been promoted only the night before to commander of Company A, and Engemann ordered him and his company of dismounted infantry into Remagen supported by A Company/14th Tank Battalion. Hoge had no intelligence on the number and size of German forces on the east bank. The standing bridge could have been a trap. Hoge risked losing men if the Germans allowed U.S. forces to cross before destroying it and isolating the American troops on the east bank. But the opportunity was too great to pass up.

Battalion Commander Major Murray Deevers asked Timmermann, “Do you think you can get your company across the bridge?” Timmermann replied, “Well, we can try it, sir.” Deevers answered, “Go ahead.” “What if the bridge blows up in my face?” Timmermann asked, but Deevers did not answer.

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Australian WWII Owen MK1 Machine Carbine SMG Custom Fabricated Replica with Sling Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armored Burgonet Helmet & Polearm from Scottish Castle Leith Hall Circa 1700 Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized