Original German WWII Fritz Sauckel Silverware Set Original Items

$ 495,00 $ 148,50

Original Items: One-of-a-kind Set. Fritz Sauckel as Gauleiter of the Thuringen and member of the Reichstag was an important leader in NSDAP Germany, based in Weimar. In 1939, AH made Sauckel Plenipotentiary of Allocation for Labor. Sauckel ran what turned out to be the largest slave trade industry in history. Although he claimed he was only supplying people for jobs, he used the example at Nuremberg, “It was like a seaman’s agency. If I supply hands for a ship, I am not responsible for cruelty that may be exercised aboard the ship without my knowledge”…

His judges didn’t buy it and Fritz Sauckel was hung at Nuremberg as a war criminal on October 6, 1946. A man this powerful had great need for entertaining as there were large numbers of Party officials around his presence, so he had an adequate silver service using the unique Thuringen eagle for the pattern. Sauckel’s silver is pattern is considered quite striking by collectors and is a very popular collectible.

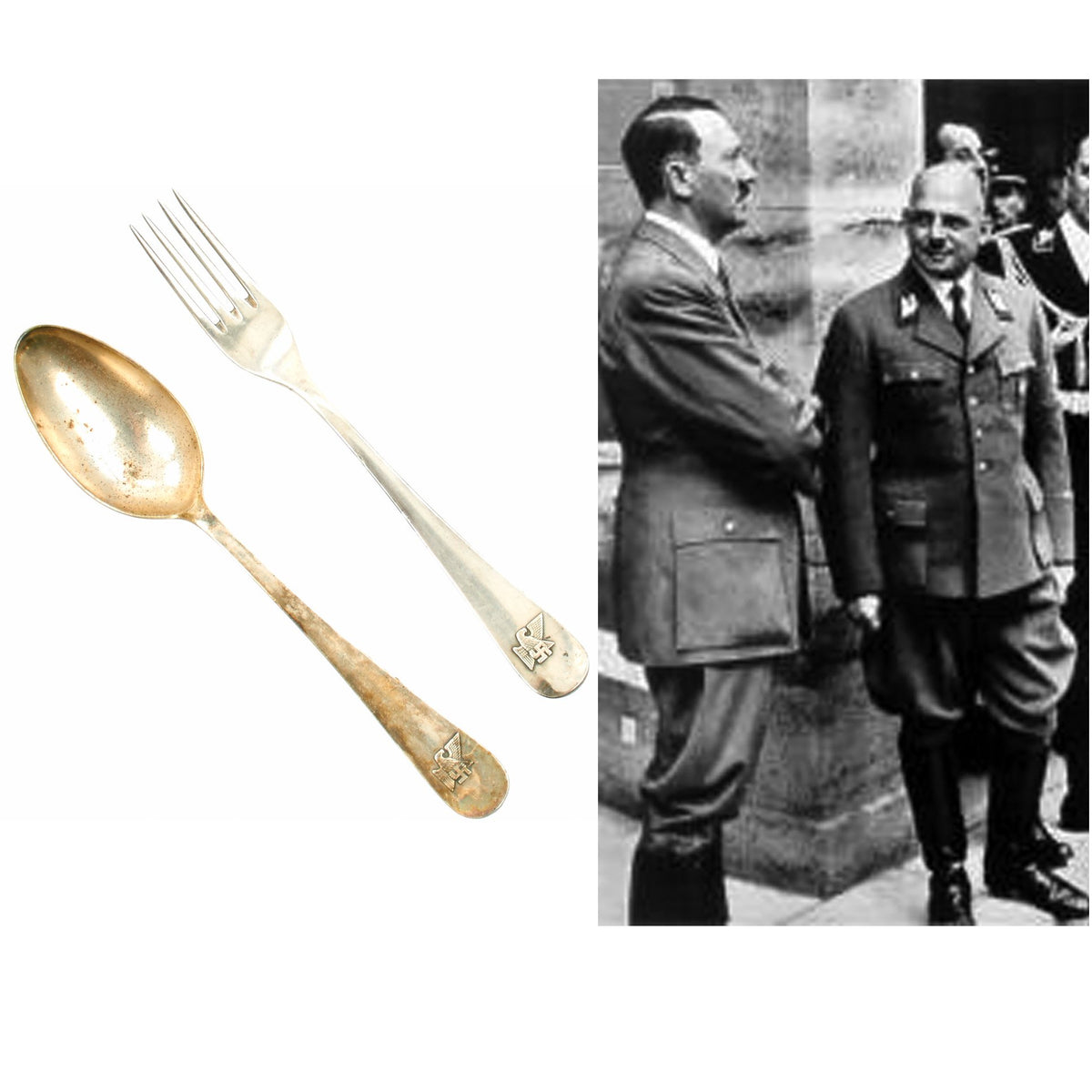

This set consists of the following items:

– Serving Spoon measures just over 8 inches long. The bowl of the spoon remains in very good condition with a fine rim. The handle of the spoon is smooth. At the bottom is the raised out Thuringen eagle, which is probably one of the best looking birds used during the Third Reich. The reverse of the spoon is marked “Bruckmann 90”, indicating silver plate. A very rare piece, given the size.

– Table Fork measures just over 8 inches long. On the lower handle is a beautiful Thuringen eagle. This very stylized bird is highly detailed and one of the best looking (if not the best) eagle designs used by the Germans. The reverse is marked “Bruckmann 90”, indicating silver plate.. A fine, rarely seen Sauckel Thuringen example.

Ernst Friedrich Christoph “Fritz” Sauckel (27 October 1894 – 16 October 1946) was a German NSDAP politician, Gauleiter of Thuringia and the General Plenipotentiary for Labour Deployment from March 1942 until the end of the Second World War.

Sauckel was among the 24 persons accused in the Nuremberg Trial of the Major War Criminals before the International Military Tribunal. He was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity, and was sentenced to death by hanging.

During World War II, he was Reich defense commissioner for the Kassel district (Reichsverteidigungskommissar Wehrkreis IX) before being appointed General Plenipotentiary for Labour Deployment (Generalbevollmächtigter für den Arbeitseinsatz) on 21 March 1942, on the recommendation of Martin Bormann.

Slave and forced labor

Sauckel worked directly under Göring through the Four-Year Plan Office, directing and controlling German labour. In response to increased demands, he met the requirement for manpower with people from the occupied territories. Voluntary numbers were insufficient and forced recruitment was introduced within a few months. Of the five million foreign workers brought to Germany, around 200,000 came voluntarily, according to Sauckel’s testimony at Nuremberg. The majority of the acquired workers originated from the Eastern territories, especially in Poland and the Soviet Union where the methods used to gain workers were very harsh. The Wehrmacht was used to pressgang local people and most were taken by force to the Reich. Conditions of work were extremely poor and discipline severe, especially for prison camp prisoners. All the latter were unpaid and provided with starvation rations, barely keeping those workers alive. Such slave labour was widely used in many German industries, including coal mining, steel making, and armaments manufacture. The use of forced and slave labour increased throughout the war, especially after Albert Speer came to replace Fritz Todt in charge of armaments production in February 1942 and demanded much more labour from Sauckel.

Trial and execution

At the Nuremberg trials, Fritz Sauckel was accused of conspiracy to commit crimes against peace; planning, initiating and waging wars of aggression; war crimes and crimes against humanity. He defended the Arbeitseinsatz as “nothing to do with exploitation. It is an economic process for supplying labour”. He denied that it was slave labour or that it was common to deliberately work people to death (extermination by labour) or to mistreat them.

All the men [prisoners of war and foreign civilian workers] must be fed, sheltered, and treated in such a way as to exploit them to the highest possible extent at the lowest conceivable degree of expenditure.

Robert Servatius, Sauckel’s counsel, portrayed Sauckel as a representative of the labour classes of Germany; an earnest and unpretentious party man assiduously committed to promoting the collective utility of the working class. This portrait was contrary to that of Speer, whom Servatius juxtaposed against Sauckel as a technical genius and entrepreneurial administrator. Sauckel surmised that Speer bore greater legal and moral responsibility by virtue of the fact that the former merely met the demands of the latter, in accordance with protocol. This strategy did not yield to his favour, however, as the ratio in the final judgement against the respective defendants outlined that Speer’s tasks were numerous, with the forced labour program comprising only one facet of his ministerial responsibilities, while Sauckel was singularly responsible for his office as General Plenipotentiary.

After a defense led by Robert Servatius, Sauckel was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity, and together with a number of colleagues was hanged at Nuremberg Prison on 16 October 1946, 11 days before his 52nd birthday. His last words were recorded as “Ich sterbe unschuldig, mein Urteil ist ungerecht. Gott beschütze Deutschland. Möge es leben und eines Tages wieder groß werden. Gott beschütze meine Familie.”[3] (“I die an innocent man, my sentence is unjust. God protect Germany! May it live and one day become great again! God protect my family.”). Albert Speer escaped the death sentence, but served 20 years at Spandau prison.

Sauckel’s body, as were those of the other nine executed men and the corpse of Hermann Göring, was cremated at Ostfriedhof (Munich) and the ashes were scattered in the river Isar.

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Band of Brothers ORIGINAL GERMAN WWII Le. F.H. 18 10.5cm ARTILLERY PIECE Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Angolan Rebel 1970s era 60mm Inert Display Mortar from Angolan Civil War Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized