Original German WWII Bronze Signed Bust of General Erich Ludendorff with Plaque Commemorating His Involvement in the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch Failed Coup Original Items

$ 895,00 $ 223,75

Original Item. Only One Available. General Erich Ludendorff was one of the most famous general officers of the First World War, most well known at the time for his central role in the German victories at Liège and Tannenberg in 1914. During the interwar period, however, he became famous again for his presence at the Beer Hall Putsch alongside AH in 1923, which became an instrumental event in the history of the NSDAP.

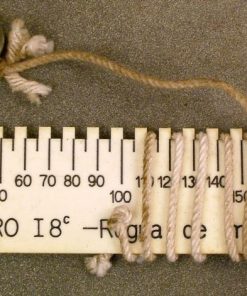

The bronze bust is signed along the back “fec. Oswald Schimmelplenning Berlin” (1872 – 1939), a well known maker of the time. The bust has been mounted onto wood with green cushioning on the bottom. A plaque is attached to the front of the wood base reading “Held der N.S.D.A.P. vom 8.11.1923”, which translates to “Hero of the N.S.D.A.P. dated November 8, 1923”. The base of the bust measures 7 ¾” x4 ½”, and the bust in total is about 9” tall. It is in phenomenal condition with almost no flaws.

Ludendorff was a well known figure in Germany in the years leading up to World War II, being made a member of the Reichstag and serving from 1920-1928. He would pass away on December 20th, 1937, almost 2 years prior to the beginning of World War II.

The Beer Hall Putsch, also known as the Munich Putsch, and, in German, as the AHputsch, AH-Ludendorff-Putsch, Bürgerbräu-Putsch or Marsch auf die Feldherrnhalle (“March on the general’s hall”), was a failed coup d’état by the NSDAP Party leader AH—along with Generalquartiermeister Erich Ludendorff and other Kampfbund leaders—to seize power in Munich, Bavaria, which took place from 8 November to 9 November 1923. Approximately two thousand NSDAPs were marching to the Feldherrnhalle, in the city center, when they were confronted by a police cordon, which resulted in the death of 16 NSDAPs and four police officers. AH, who was wounded during the clash, escaped immediate arrest and was spirited off to safety in the countryside. After two days, he was arrested and charged with treason.

The putsch brought AH to the attention of the German nation and generated front-page headlines in newspapers around the world. His arrest was followed by a 24-day trial, which was widely publicised and gave him a platform to publicise his nationalist sentiment to the nation. AH was found guilty of treason and sentenced to five years in Landsberg Prison, where he dictated Mein Kampf to his fellow prisoners Emil Maurice and Rudolf Hess. On 20 December 1924, having served only nine months, AH was released. AH now saw that the path to power was through legal means rather than revolution or force, and accordingly changed his tactics, further developing NSDAP propaganda.

Background

In the early 20th century, many of the larger cities of southern Germany had beer halls where hundreds or even thousands of people would socialise in the evenings, drink beer and participate in political and social debates. Such beer halls also became the host of occasional political rallies. One of Munich’s largest beer halls was the Bürgerbräukeller. This was the location of the Putsch.

The Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I, sounded the death knell of German power and prestige. Like many Germans of the period, AH (who still held Austrian citizenship at the time) believed that the treaty was a betrayal, with the country having been “stabbed in the back” by its own government, particularly as the German Army was popularly thought to have been undefeated in the field. Germany, it was felt, had been betrayed by civilian leaders and Marxists, who were later called the “November Criminals”.

AH remained in the army, in Munich, after World War I. He participated in various “national thinking” courses. These had been organized by the Education and Propaganda Department of the Bavarian Army, under Captain Karl Mayr, of which AH became an agent. Captain Mayr ordered AH, then an army lance corporal, to infiltrate the tiny Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, abbreviated DAP (German Workers’ Party). AH joined the DAP on 12 September 1919. He soon realized that he was in agreement with many of the underlying tenets of the DAP, and he rose to its top post in the ensuing chaotic political atmosphere of postwar Munich. By agreement, AH assumed the political leadership of a number of Bavarian “patriotic associations” (revanchist), called the Kampfbund. This political base extended to include about 15,000 Sturmabteilung (SA, lit. “Storm Detachment”), the paramilitary wing of the NSDAP.

On 26 September 1923, following a period of turmoil and political violence, Bavarian Prime Minister Eugen von Knilling declared a state of emergency, and Gustav von Kahr was appointed Staatskomissar, or state commissioner, with dictatorial powers to govern the state. In addition to von Kahr, Bavarian state police chief Colonel Hans Ritter von Seisser and Reichswehr General Otto von Lossow formed a ruling triumvirate. AH announced that he would hold 14 mass meetings beginning on 27 September 1923. Afraid of the potential disruption, one of Kahr’s first actions was to ban the announced meetings. AH was under pressure to act. The NSDAPs, with other leaders in the Kampfbund, felt they had to march upon Berlin and seize power or their followers would turn to the Communists. AH enlisted the help of World War I general Erich Ludendorff in an attempt to gain the support of Kahr and his triumvirate. However, Kahr had his own plan with Seisser and Lossow to install a nationalist dictatorship without AH.

The Putsch

The attempted putsch was inspired by Benito Mussolini’s successful March on Rome, from 22 to 29 October 1922. AH and his associates planned to use Munich as a base for a march against Germany’s Weimar Republic government. But the circumstances were different from those in Italy. AH came to the realisation that Kahr sought to control him and was not ready to act against the government in Berlin. AH wanted to seize a critical moment for successful popular agitation and support. He decided to take matters into his own hands. AH, along with a large detachment of SA, marched on the Bürgerbräukeller, where Kahr was making a speech in front of 3,000 people.

In the cold, dark evening, 603 SA surrounded the beer hall and a machine gun was set up in the auditorium. AH, surrounded by his associates Hermann Göring, Alfred Rosenberg, Rudolf Hess, Ernst Hanfstaengl, Ulrich Graf, Johann Aigner, Adolf Lenk, Max Amann, Max Erwin von Scheubner-Richter, Wilhelm Adam, and others (some 20 in all), advanced through the crowded auditorium. Unable to be heard above the crowd, AH fired a shot into the ceiling and jumped on a chair yelling: “The national revolution has broken out! The hall is filled with six hundred men. Nobody is allowed to leave.” He went on to state the Bavarian government was deposed and declared the formation of a new government with Ludendorff.

AH, accompanied by Hess, Lenk, and Graf, ordered the triumvirate of Kahr, Seisser, and Lossow into an adjoining room at gunpoint and demanded they support the putsch. AH demanded they accept government positions he assigned them. AH had promised Lossow a few days earlier that he would not attempt a coup, but now thought that he would get an immediate response of affirmation from them, imploring Kahr to accept the position of Regent of Bavaria. Kahr replied that he could not be expected to collaborate, especially as he had been taken out of the auditorium under heavy guard.

Heinz Pernet, Johann Aigne and Scheubner-Richter were dispatched to pick up Ludendorff, whose personal prestige was being harnessed to give the NSDAPs credibility. A telephone call was made from the kitchen by Hermann Kriebel to Ernst Röhm, who was waiting with his Bund Reichskriegsflagge in the Löwenbräukeller, another beer hall, and he was ordered to seize key buildings throughout the city. At the same time, co-conspirators under Gerhard Rossbach mobilised the students of a nearby Officers Infantry school to seize other objectives.

AH became irritated by Kahr and summoned Ernst Pöhner, Friedrich Weber and Hermann Kriebel to stand in for him while he returned to the auditorium flanked by Rudolf Hess and Adolf Lenk. He followed up on Göring’s speech and stated that the action was not directed at the police and Reichswehr, but against “…the Berlin Jew government and the November criminals of 1918”. Dr. Karl Alexander von Mueller, a professor of modern history and political science at the University of Munich and a supporter of Kahr, was an eyewitness. He reported:

I cannot remember in my entire life such a change in the attitude of a crowd in a few minutes, almost a few seconds … AH had turned them inside out, as one turns a glove inside out, with a few sentences. It had almost something of hocus-pocus, or magic about it.

AH ended his speech with: “Outside are Kahr, Lossow and Seisser. They are struggling hard to reach a decision. May I say to them that you will stand behind them?”

The crowd in the hall backed AH with a roar of approval. He finished triumphantly:

You can see that what motivates us is neither self-conceit or self-interest, but only a burning desire to join the battle in this grave eleventh hour for our German Fatherland … One last thing I can tell you. Either the German revolution begins tonight or we will all be dead by dawn!

AH returned to the anteroom, where the triumvirs remained, to ear-shattering acclaim, which the triumvirs could not have failed to notice. On his way back, AH ordered Göring and Hess to take Eugen von Knilling and seven other members of the Bavarian government into custody.

During AH’s speech, Pöhner, Weber, and Kriebel had been trying in a conciliatory fashion to bring the triumvirate round to their point of view. The atmosphere in the room had become lighter but Kahr continued to dig in his heels. Ludendorff showed up a little before 21:00 (9 p.m.) and, being shown into the ante-room, concentrated on Lossow and Seisser, appealing to their sense of duty. Eventually, the triumvirate reluctantly gave in.

AH, Ludendorff et al. returned to the main hall’s podium, where they gave speeches and shook hands. The crowd was then allowed to leave the hall.[23] In a tactical mistake, AH decided to leave the Bürgerbräukeller shortly thereafter to deal with a crisis elsewhere. Around 22:30 (10:30 p.m.), Ludendorff released Kahr and his associates.

The night was marked by confusion and unrest among government officials, armed forces, police units, and individuals deciding where their loyalties lay. Units of the Kampfbund were scurrying around to arm themselves from secret caches, and seizing buildings. At around 3 a.m., the first casualties of the putsch occurred when the local garrison of the Reichswehr spotted Röhm’s men coming out of the beer hall. They were ambushed while trying to reach the Reichswehr barracks by soldiers and state police; shots were fired, but there were no fatalities on either side. Encountering heavy resistance, Röhm and his men were forced to fall back. In the meantime, the Reichswehr officers put the whole garrison on alert and called for reinforcements. Foreign attachés were seized in their hotel rooms and put under house arrest.

In the early morning, AH ordered the seizure of the Munich city council as hostages. He further sent the communications officer of the Kampfbund, Max Neunzert, to enlist the aid of Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria to mediate between Kahr and the putschists. Neunzert failed in the mission.

By midmorning on 9 November, AH realized that the putsch was going nowhere. The Putschists did not know what to do and were about to give up. At this moment, Ludendorff cried out, “Wir marschieren!” (We will march!). Röhm’s force together with AH’s (a total of approximately 2000 men) marched out—but with no specific plan of where to go. On the spur of the moment, Ludendorff led them to the Bavarian Defense Ministry. However, at the Odeonsplatz in front of the Feldherrnhalle, they met a force of 130 soldiers blocking the way under the command of State Police Senior Lieutenant Baron Michael von Godin. The two groups exchanged fire, killing four state police officers and 16 NSDAPs.

This was the origin of the Blutfahne (blood-flag), which became stained with the blood of two SA members who were shot: the flagbearer Heinrich Trambauer, who was badly wounded, and Andreas Bauriedl, who fell dead onto the fallen flag. A bullet killed Scheubner-Richter. Göring was shot in the leg, but escaped. The rest of the NSDAPs scattered or were arrested. AH was arrested two days later.

In a description of Ludendorff’s funeral at the Feldherrnhalle in 1937 (which AH attended but without speaking) William L. Shirer wrote: “The World War [One] hero [Ludendorff] had refused to have anything to do with him [AH] ever since he had fled from in front of the Feldherrnhalle after the volley of bullets during the Beer Hall Putsch.” However, when a consignment of papers relating to Landsberg prison (including the visitor book) were later sold at auction, it was noted that Ludendorff had visited AH a number of times. The case of the resurfacing papers was reported in Der Spiegel (“The Mirror”, German news magazine) on 23 June 2006; the new information (which came out more than 30 years after Shirer wrote his book, and which Shirer did not have access to) nullifies Shirer’s statement.

Counterattack

State Police and Police units were first notified of trouble by three police detectives stationed at the Löwenbräukeller. These reports reached Major Sigmund von Imhoff of the State police. He immediately called all his green police units and had them seize the central telegraph office and the telephone exchange, although his most important act was to notify Major-General Jakob von Danner, the Reichswehr city commandant of Munich. As a staunch aristocrat, Danner loathed the “little corporal” and those “Freikorps bands of rowdies”. He also did not much like his commanding officer, Generalleutnant Otto von Lossow, “a sorry figure of a man”. He was determined to put down the putsch with or without Lossow. Danner set up a command post at the 19th Infantry Regiment barracks and alerted all military units.

Meanwhile, Captain Karl Wild, learning of the putsch from marchers, mobilised his command to guard Kahr’s government building, the Commissariat, with orders to shoot.

Around 23:00 (11 p.m.), Major-General von Danner, along with fellow generals Adolf Ritter von Ruith [de] and Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein, compelled Lossow to repudiate the putsch.

There was one member of the cabinet who was not at the Bürgerbräukeller: Franz Matt, the vice-premier and minister of education and culture. A staunchly conservative Roman Catholic, he was having dinner with the Archbishop of Munich, Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber and with the Nuncio to Bavaria, Archbishop Eugenio Pacelli (who would later become Pope Pius XII), when he learned of the putsch. He immediately telephoned Kahr. When he found the man vacillating and unsure, Matt decisively began plans to set up a rump government-in-exile in Regensburg and composed a proclamation calling upon all police officers, members of the armed forces, and civil servants to remain loyal to the government. The action of these few men spelled doom for those attempting the putsch.

On Wednesday, 3,000 students from the University of Munich rioted and marched to the Feldherrnhalle to lay wreaths. They continued to riot until Friday, when they learned of AH’s arrest. Kahr and Lossow were called Judases and traitors.

Trial and prison

Two days after the putsch, AH was arrested and charged with high treason in the special People’s Court. Some of his fellow conspirators, including Rudolf Hess, were also arrested, while others, including Hermann Göring and Ernst Hanfstaengl, escaped to Austria. The NSDAP Party’s headquarters was raided, and its newspaper, the Völkischer Beobachter (“The People’s Observer”), was banned. In January 1924, the Emminger Reform, an emergency decree, abolished the jury as trier of fact and replaced it with a mixed system of judges and lay judges in Germany’s judiciary, which still exists.

This was not the first time AH had been in trouble with the law. In an incident in September 1921, he and some men of the SA had disrupted a meeting of the Bayernbund (“Bavaria Union”) which Otto Ballerstedt, a Bavarian federalist, was to have addressed, and the NSDAPs who had gone there to cause trouble were arrested as a result. AH ended up serving a little over a month of a three-month jail sentence. Judge Georg Neithardt (de) was the presiding judge at both of AH’s trials.

AH’s trial began on 26 February 1924 and lasted until 1 April 1924. Lossow acted as chief witness for the prosecution. AH moderated his tone for the trial, centering his defence on his selfless devotion to the good of the people and the need for bold action to save them; dropping his usual anti-Semitism.[36] He claimed the putsch had been his sole responsibility, inspiring the title “Führer” or “Leader”. The lay judges were fanatically pro-NSDAP and had to be dissuaded by the presiding Judge, Georg Neithardt (de), from acquitting AH.[38] AH and Hess were both sentenced to five years in Festungshaft [de] (literally fortress confinement) for treason. Festungshaft was the mildest of the three types of jail sentence available in German law at the time; it excluded forced labour, provided reasonably comfortable cells, and allowed the prisoner to receive visitors almost daily for many hours. This was the customary sentence for those whom the judge believed to have had honorable but misguided motives, and it did not carry the stigma of a sentence of Gefängnis or Zuchthaus. In the end, AH served only a little over eight months of this sentence before his early release for good behaviour.

However, AH used the trial as an opportunity to spread his ideas by giving speeches to the court room. The event was extensively covered in the newspapers the next day. The judges were impressed (Presiding Judge Neithardt was inclined to favoritism towards the defendants prior to the trial), and as a result, AH served a little over eight months and was fined 500 Reichsmark. Due to his story that he was present by accident, an explanation he had also used in the Kapp Putsch, along with his war service and connections, Ludendorff was acquitted. Both Röhm and Wilhelm Frick, though found guilty, were released. Göring, meanwhile, had fled after suffering a bullet wound to his leg, which led him to become increasingly dependent on morphine and other painkilling drugs. This addiction continued throughout his life.

One of AH’s greatest worries at the trial was that he was at risk of being deported back to his native Austria by the Bavarian government. The trial judge, Neithardt, was very sympathetic towards AH and held that the relevant laws of the Weimar Republic could not be applied to a man “who thinks and feels like a German, as AH does.” The result was that the NSDAP leader remained in Germany.

Though AH failed to achieve his immediate stated goal, the putsch did give the NSDAPs their first exposure to national attention and a propaganda victory. While serving their “fortress confinement” sentences at Landsberg am Lech, AH, Emil Maurice and Rudolf Hess wrote Mein Kampf. Also, the putsch changed AH’s outlook on violent revolution to effect change. From then on he thought that, in order to win the German heart, he must do everything by the book, “strictly legal”.

The process of combination, where the conservative-nationalist-monarchist group thought that its members could piggyback onto, and control, the National Socialist movement to garner the seats of power, was to repeat itself ten years later in 1933 when Franz von Papen legally asked AH to form a coalition government.

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armored Burgonet Helmet & Polearm from Scottish Castle Leith Hall Circa 1700 Original Items

Uncategorized

Band of Brothers ORIGINAL GERMAN WWII Le. F.H. 18 10.5cm ARTILLERY PIECE Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Angolan Rebel 1970s era 60mm Inert Display Mortar from Angolan Civil War Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armoured Fighting Vehicles of the World: AFVs of World War One (Hardcover Book) New Made Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized