Original German WWII 1941 Dated Luftwaffe Navigator Soft Laminate “Half” Map For The Arctic Ocean / Norway – 36 ½” x 23” Original Items

$ 175,00 $ 70,00

Original Item: Only One Available. The occupation of Norway by Germany during the Second World War began on 9 April 1940 after Operation Weserübung. Conventional armed resistance to the German invasion ended on 10 June 1940, and NSDAP Germany controlled Norway until the capitulation of German forces in Europe on 8/9 May 1945. Throughout this period, a pro-German government named Den nasjonale regjering ruled Norway, while the Norwegian king Haakon VII and the prewar government escaped to London, where they formed a government in exile. Civil rule was effectively assumed by the Reichskommissariat Norwegen (Reich Commissariat of Norway), which acted in collaboration with the pro-German puppet government. This period of military occupation is, in Norway, referred to as the “war years”, “occupation period” or simply “the war”.

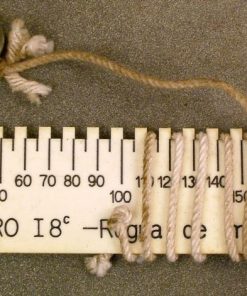

The map does have a 1941 date visible but not much of any other stamps visible. This map has roads, towns/cities, major highways, mountain ranges, bodies of water and other land identifiers featured on the map. The reverse side has a small 1:000 000 aeronautical map of the world.

Comes more than ready for further research and display.

On the pretext that Norway needed protection from British and French interference, Germany invaded Norway for several reasons:

-strategically, to secure ice-free harbors from which its naval forces could seek to control the North Atlantic;

-to secure the availability of iron ore from mines in Sweden, going through Narvik;

-to pre-empt a British and French invasion with the same purpose; and

-to reinforce the propaganda of a “Germanic empire”.

Through neglect both on the part of the Norwegian foreign minister Halvdan Koht and minister of defense Birger Ljungberg, Norway was largely unprepared for the German military invasion when it came on the night of 8–9 April 1940. A major storm on 7 April resulted in the British Navy failing to make material contact with the German shipping. Consistent with Blitzkrieg warfare, German forces attacked Norway by sea and air as Operation Weserübung was put into action. The first wave of German attackers counted only about 10,000 men. German ships came into the Oslofjord, but were stopped when the Krupp-built artillery and torpedoes of Oscarsborg Fortress sank the German flagship Blücher and sank or damaged the other ships in the German task force. Blücher transported the forces that would ensure control of the political apparatus in Norway, and the sinking and death of over 1,000 soldiers and crew delayed the Germans, so that the King and government had the chance to escape from Oslo. In the other cities that were attacked, the Germans faced only weak or no resistance. The surprise and the lack of preparedness of Norway for a large-scale invasion of this kind gave the German forces their initial success.

The major Norwegian ports from Oslo northward to Narvik (more than 1,200 mi (1,900 km) away from Germany’s naval bases) were occupied by advance detachments of German troops, transported on destroyers. At the same time, a single parachute battalion took the Oslo and Stavanger airfields, and 800 operational aircraft overwhelmed the Norwegian population. Norwegian resistance at Narvik, Trondheim (Norway’s second city and the strategic key to Norway), Bergen, Stavanger, and Kristiansand was overcome very quickly, and Oslo’s effective resistance to the seaborne forces was nullified when German troops from the airfield entered the city. The first troops to occupy Oslo entered the city brazenly, marching behind a German military brass band.

On establishing footholds in Oslo and Trondheim, the Germans launched a ground offensive against scattered resistance inland in Norway. Allied forces attempted several counterattacks, but all failed. While resistance in Norway had little military success, it had the significant political effect of allowing the Norwegian government, including the royal family, to escape. The Blücher, which carried the main forces to occupy the capital, was sunk in the Oslofjord on the first day of the invasion. An improvised defense at Midtskogen also prevented a German raid from capturing the king and government.

Norwegian mobilization was hampered by the loss of much of the best equipment to the Germans in the first 24 hours of the invasion, the unclear mobilization order by the government, and the general confusion caused by the tremendous psychological shock of the German surprise attack. The Norwegian Army rallied after the initial confusion and on several occasions managed to put up a stiff fight, delaying the German advance. However, the Germans, quickly reinforced by Panzer and motorized machine gun battalions, proved unstoppable due to their superior numbers, training, and equipment. The Norwegian Army therefore planned its campaign as a tactical retreat while awaiting reinforcements from Britain.

The British Navy cleared the way to Narvik on 13 April, sinking one submarine and eight destroyers in the fjord. British and French troops began to land at Narvik on 14 April. Shortly afterward, British troops landed at Namsos and Åndalsnes, to attack Trondheim from the north and from the south, respectively. The Germans, however, landed fresh troops in the rear of the British at Namsos and advanced up the Gudbrandsdal from Oslo against the force at Åndalsnes. By this time, the Germans had about 25,000 men in Norway.

By 23 April, there was open discussion about evacuating Allied troops, and on 24 April Norwegian troops, supported by French soldiers, failed to stop a Panzer advance. On 26 April the British decided to evacuate Norway.

By 2 May, both Namsos and Åndalsnes were evacuated by the British. On 5 May, the last Norwegian resistance pockets remaining in South and Central Norway were defeated at Vinjesvingen and Hegra Fortress.

In the north, German troops engaged in a bitter fight at the Battle of Narvik. Holding out against five times as many British and French troops, they were close to rebellion before finally slipping out from Narvik on 28 May. Moving east, the Germans were surprised when the British started to abandon Narvik on 3 June. By that time the German offensive in France had progressed to such an extent that the British could no longer afford any commitment in Norway, and the 25,000 Britons and Frenchmen were evacuated from Narvik only 10 days after their victory. King Haakon VII and part of his government left for England on the British cruiser HMS Glasgow to establish the Norwegian government-in-exile.

Fighting continued in Northern Norway until 10 June, when the Norwegian 6th Division surrendered shortly after Allied forces had been evacuated against the background of looming defeat in France. Among German-occupied territories in Western Europe, this made Norway the country to withstand the German invasion for the longest period of time – approximately two months.

About 300,000 Germans were garrisoned in Norway for the rest of the war. By occupying Norway, Adolf H had ensured the protection of Germany’s supply of iron ore from Sweden and had obtained naval and air bases with which to strike at Britain.

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Australian WWII Owen MK1 Machine Carbine SMG Custom Fabricated Replica with Sling Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

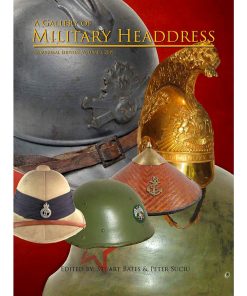

Armoured Fighting Vehicles of the World: AFVs of World War One (Hardcover Book) New Made Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armored Burgonet Helmet & Polearm from Scottish Castle Leith Hall Circa 1700 Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized