Original German Pre-WWI Imperial Navy Kaiserliche Marine Dress Jacket Dated 1910 Original Items

$ 395,00 $ 118,50

Original Item: Only One Available. The Dress Jacket (“Affenjacke”) was made of dark blue wool and had eight brass (or white metal) buttons down either side, although it was actually loosely held by a small chain between two additional buttons. The cuffs likewise had eight buttons but are missing from this example. NCO rank was displayed by a single chevron on the upper left arm for junior NCOs and lace on the cuffs for senior NCOs, this one has no rank insignia present. In the mid 19th Century the dress jacket had been standard wear for Prussian (and later German) sailors, but in the early twentieth century it was worn only on parade or for special occasions.

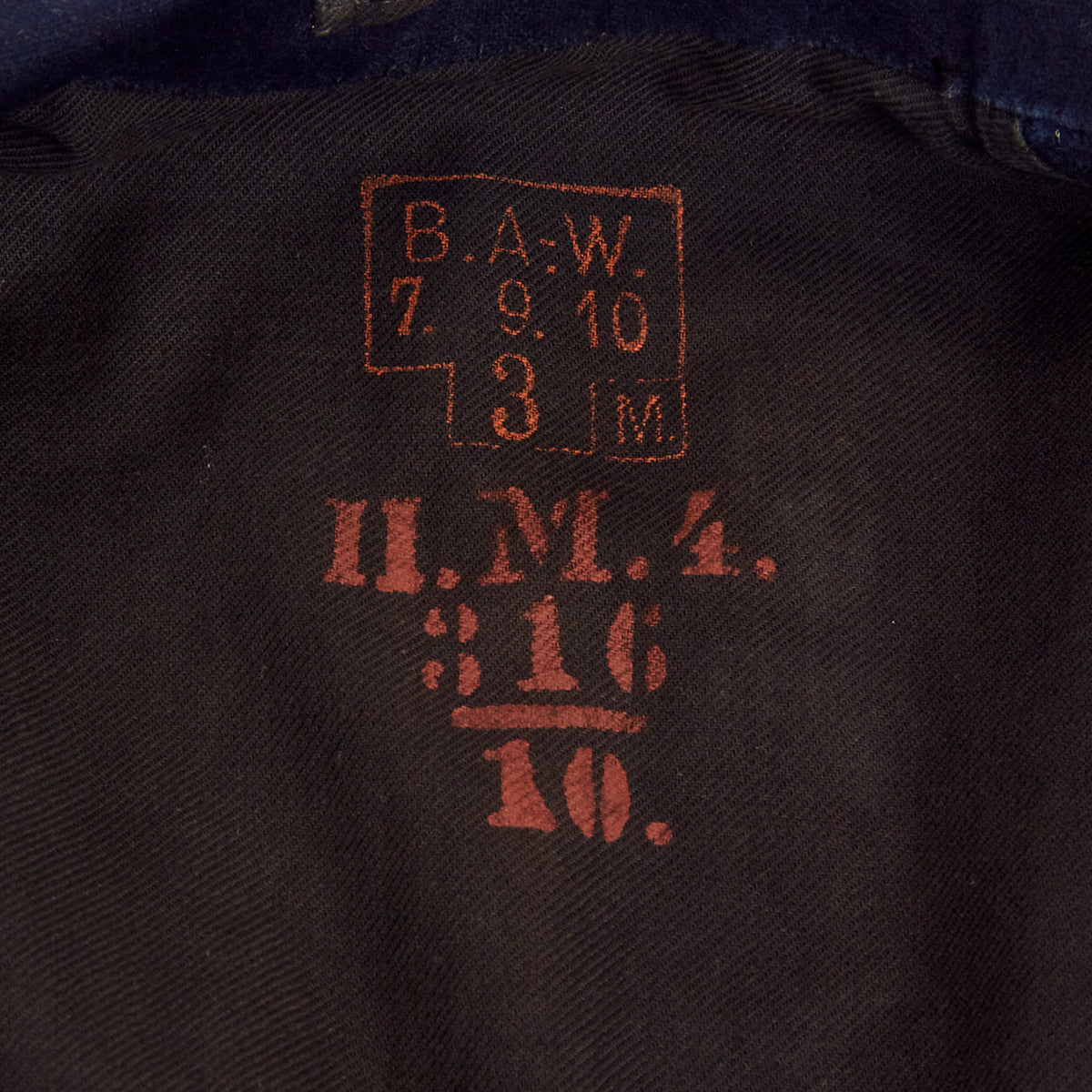

This example is in wonderful condition and retains all buttons except for the cuffs and top three buttons on the right side. There is minor mothing present but nothing too extensive or damaging. The back lining of the coat still retains full arsenal stamping:

B. A.-W.

7. 9. 10

3 M

H.M.4

316

—

10

A wonderful example ready for further research and display.

Approximate Measurements

Collar to shoulder: 9″

Shoulder to sleeve: 24.5”

Shoulder to shoulder: 14.5”

Chest width: 15”

Waist width: 15″

Hip width: 15”

Front length: 23.5″

The Kaiserliche Marine:

The Imperial German Navy or the Imperial Navy (German: Kaiserliche Marine) was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for coast defense. Kaiser Wilhelm II greatly expanded the navy. The key leader was Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, who greatly expanded the size and quality of the navy, while adopting the sea power theories of American strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan. The result was a naval arms race with Britain, as the German navy grew to become one of the greatest maritime forces in the world, second only to the Royal Navy.

The German surface navy proved ineffective during the First World War; its only major engagement, the Battle of Jutland, was a draw, but it kept the surface fleet largely in port for the rest of the war. The submarine fleet was greatly expanded and threatened the British supply system during the U-boat campaign. As part of the Armistice, the Imperial Navy’s main ships were ordered to be turned over to the Allies but they were instead scuttled by their own crews. All ships of the Imperial Navy bore the title SMS, for Seiner Majestät Schiff (His Majesty’s Ship).

The Imperial Navy achieved some important operational feats. At the Battle of Coronel, it inflicted the first major defeat on the Royal Navy in over one hundred years, although the German squadron of ships was subsequently defeated at the Battle of the Falkland Islands, only one ship escaping destruction. The Navy also emerged from the fleet action of the Battle of Jutland having destroyed more ships than it lost, although the strategic value of both of these encounters was minimal.

The Imperial Navy was the first to operate submarines successfully on a large scale in wartime, with 375 submarines commissioned by the end of the First World War, and it also operated zeppelins. Although it was never able to match the number of ships of the Royal Navy, it had technological advantages, such as better shells and propellant for much of the Great War, meaning that it never lost a ship to a catastrophic magazine explosion from an above-water attack, although the elderly pre-dreadnought SMS Pommern sank rapidly at Jutland after a magazine explosion was caused by an underwater attack.

Spending on the navy increased inexorably year by year. In 1909 Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow and Treasury Secretary Reinhold von Sydow attempted to pass a new budget boosting taxes in an attempt to reduce the deficit. The Social Democratic parties refused to accept the increased taxes on goods, while the conservatives opposed increases in inheritance taxes. Bülow and Sydow resigned in defeat and Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg became Chancellor. His attempted solution was to initiate negotiations with Britain for an agreed slow down in naval building. Negotiations came to nothing when in 1911 the Agadir Crisis brought France and Germany into conflict. Germany attempted to ‘persuade’ France to cede territory in the Middle Congo in return for giving France a free hand in Morocco. The effect was to raise concerns in Britain over Germany’s expansionist aims, and encouraged Britain to form a closer relationship with France, including naval cooperation. Tirpitz saw this once again as an opportunity to press for naval expansion and the continuation of the four capital ships per year building rate into 1912. The January 1912 elections brought a Reichstag where the Social Democrats, opposed to military expansion, became the largest party.

The German army, mindful of the steadily increasing proportion of spending going to the navy, demanded an increase of 136,000 men to bring its size closer to that of France. In February 1912 the British war minister, Viscount Haldane, came to Berlin to discuss possible limits to naval expansion. Meanwhile, in Britain, the First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill made a speech describing the German navy as a ‘luxury’, which was considered an insult when reported in Germany. The talks came to nothing, ending in recriminations over who had offered what. Bethmann-Hollweg argued for a guaranteed proportion of expenditure for the army, but failed when army officers refused to support him publicly. Tirpitz argued for six new capital ships, and got three, together with 15,000 additional sailors in a new combined military budget passed in April 1912. The new ships, together with the existing reserve flagship and four reserve battleships were to become one new squadron for the High Seas Fleet. In all the fleet would have five squadrons of eight battleships, twelve large cruisers and thirty small, plus additional cruisers for overseas duties. Tirpitz intended that with the rolling program of replacements, the existing coastal defense squadron of old ships would become a sixth fleet squadron, while the eight existing battle-cruisers would be joined by eight more as replacements for the large cruisers presently in the overseas squadrons. The plan envisaged a main fleet of 100,000 men, 49 battleships and 28 battlecruisers by 1920. The Kaiser commented of the British, “… we have them up against the wall.”

Although Tirpitz had succeeded in getting more ships, the proportion of military expenditure on the navy declined in 1912 and thereafter, from 35% in 1911 to 33% in 1912 and 25% in 1913. This reflected a change in attitude amongst military planners that a land war in Europe was increasingly likely, and a turning away from Tirpitz’s scheme for worldwide expansion using the navy. In 1912 General von Moltke commented, “I consider war to be unavoidable, and the sooner the better.” The Kaiser’s younger brother, Admiral Prince Heinrich of Prussia, considered that the cost of the navy was now too great. In Britain, Churchill announced an intention to build two capital ships for every one constructed by Germany, and reorganized the fleet to move battleships from the Mediterranean to Channel waters. A policy was introduced of promoting British naval officers by merit and ability rather than time served, which saw rapid promotions for Jellicoe and Beatty, both of whom had important roles in the forthcoming World War I. By 1913 the French and British had plans in place for joint naval action against Germany, and France moved its Atlantic fleet from Brest to Toulon, replacing British ships.

Britain also escalated the arms race by expanding the capabilities of its new battleships. The five 1912 Queen Elizabeth class of 32,000 tons would have 15 in (380 mm) guns and would be completely oil-fueled, allowing a speed of 25 knots. For 1912–13 Germany concentrated on battlecruisers, with three Derfflinger-class ships of 27,000 tons and 26–27 knots maximum speed, costing 56–59 million marks each. These had four turrets mounting two 30.5 cm guns arranged in two turrets either end, with the inner turret superfiring over the outer. SMS Derfflinger was the first German ship to have anti-aircraft guns fitted.

In 1913, Germany responded to the British challenge by laying down two Bayern class battleships. These did not enter service until after the Battle of Jutland, so failed to take part in any major naval action of the war. They had displacement of 28,600 tons, a crew of 1,100 and a speed of 22 knots, costing 50 million marks. Guns were arranged in the same pattern as the preceding battle-cruisers, but were now increased to 38 cm (15 in) diameter. The ships had four 8.8 cm anti-aircraft and also sixteen 15 cm lighter guns, but were coal fueled. It was considered that coal bunkers at the sides of the ship added to protection against penetrating shells, but Germany also did not have a reliable supply of fuel oil. Two more ships of the class were later laid down, but never completed.

Three light cruisers commenced construction in German yards in 1912–1913 ordered by the Russian Navy, costing around 9 million marks. The ships were seized at the outbreak of World War I becoming SMS Regensburg, SMS Pillau and SMS Elbing. Two larger cruisers, SMS Wiesbaden and SMS Frankfurt were also commenced and entered service in 1915. More torpedo boats were constructed, with gradually increasing sizes having reached 800 tons for the V-25 to V-30 craft constructed by AG Vulcan in Kiel before 1914. In 1912 Germany created a Mediterranean squadron consisting of the battlecruiser Goeben and light cruiser Breslau.

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Australian WWII Owen MK1 Machine Carbine SMG Custom Fabricated Replica with Sling Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armoured Fighting Vehicles of the World: AFVs of World War One (Hardcover Book) New Made Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armored Burgonet Helmet & Polearm from Scottish Castle Leith Hall Circa 1700 Original Items

Uncategorized