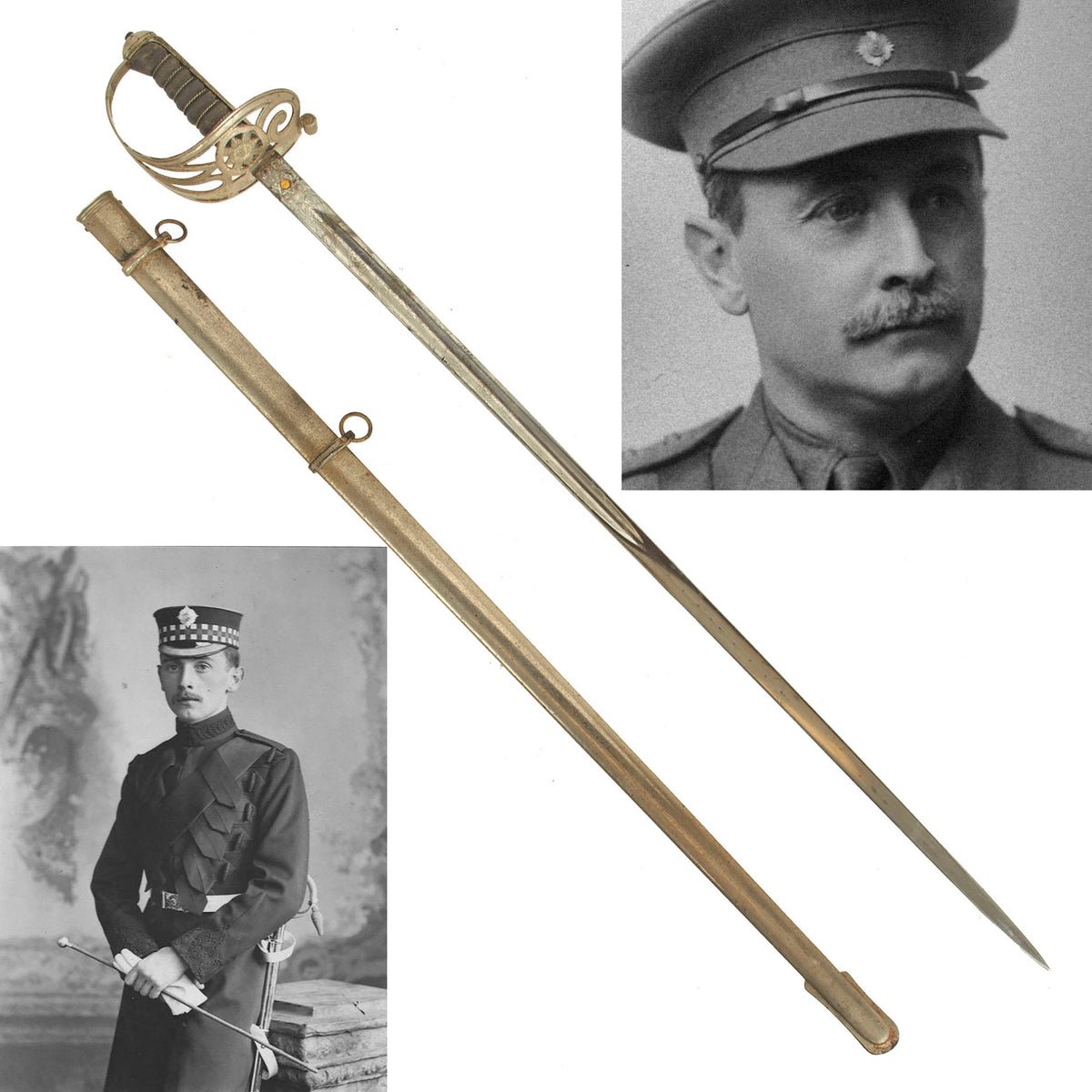

Original British WWI Pattern 1895 Light Officer’s Sword and Scabbard by Wilkinson Sword Company Attributed To Major J.S. Thorpe. M.C., Scots Guard Original Items

$ 2.195,00 $ 548,75

Original Item: Only One Available. In the 1890s a rapid succession of regulation changes happened to British infantry officers’ swords. The change was to move away from a cut and thrust saber blade and towards a specialized straight thrusting sword.

The introduction of the new thrusting blade was quickly followed by improvements to the handle and guard of the hilt, intended to provide a better grip and greater protection to the hand.

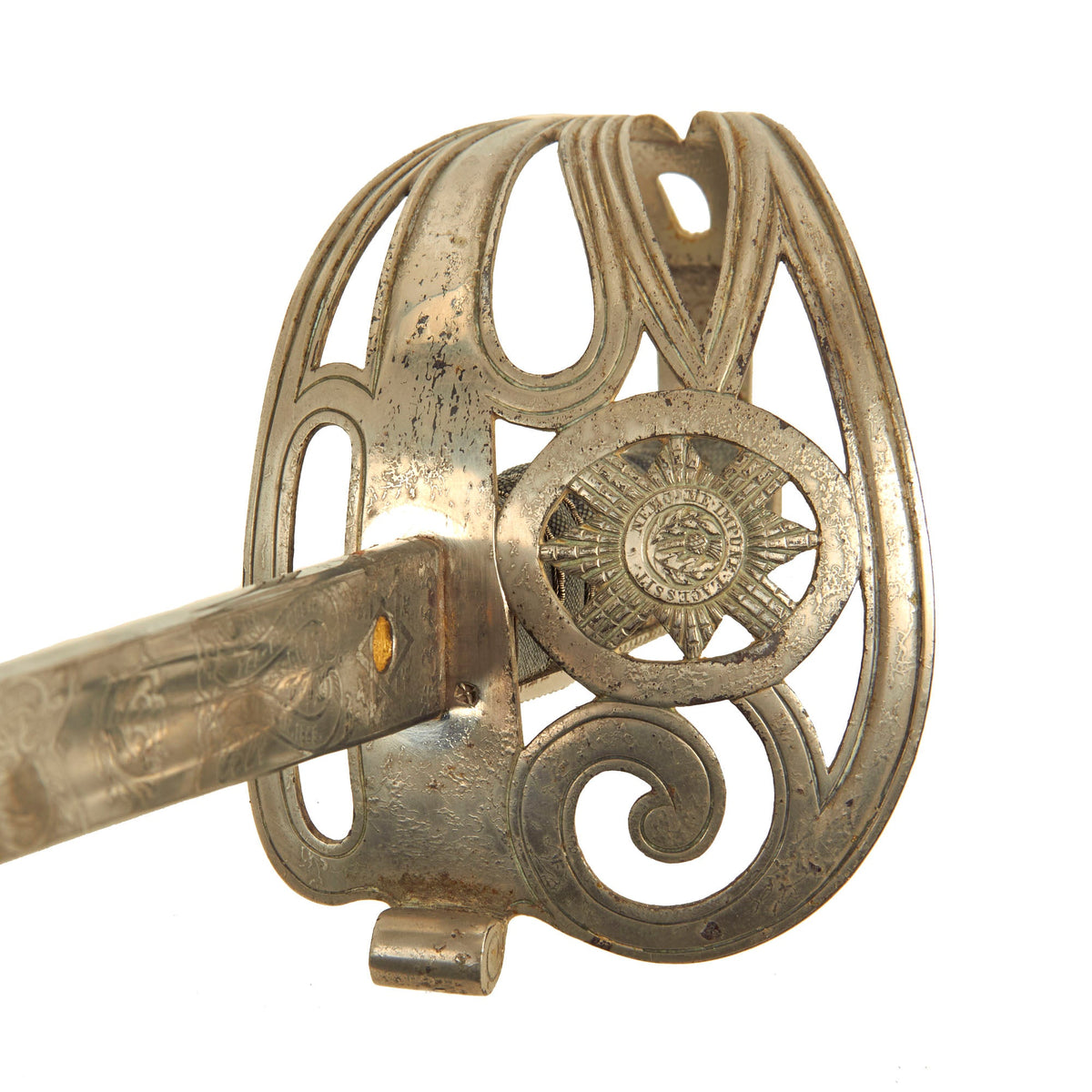

This P-1895 Officers’ sword is a wonderful example of those changes made, and is an incredible British Infantry Officers Sword. This Victorian-era infantry officer’s sword features a single fullered etched blade and beautiful gothic style hilt in gilt brass. The basket is marked with the Scots Guard Regimental Badge. This is also seen on either side of the blade in the etching.

The blade ricasso has the standard 6 pointed star around a brass plug stamped PROVED, and the reverse bears the maker information:

HENRY

WILKINSON

PALL MALL

LONDON

Shark skin grip is complete and shows light wear. The basket retains a fair amount of patina in some spots. The blade etching and embossing shows wear from cleaning. There is very little pitting or severe wear to the blade, though there is no play in the blade at the grip.

The spine is engraved with the serial number 34264, which according to records, it states that this sword was purchased from the Wilkinson Sword Company on July 17, 1896 by J.S. Thorpe, Scots Guards.

This would make an excellent display piece for any British Victorian Era collection. Ready to display!

Specifications:

Blade Length: 32 1/2″

Blade Style: Single Edge w/ Fuller

Overall length: 38 1/2“

Guard: 5 1/2″L x 4 1/2″W

Scabbard Length: 33 1/2″

Major Jim Thorpe

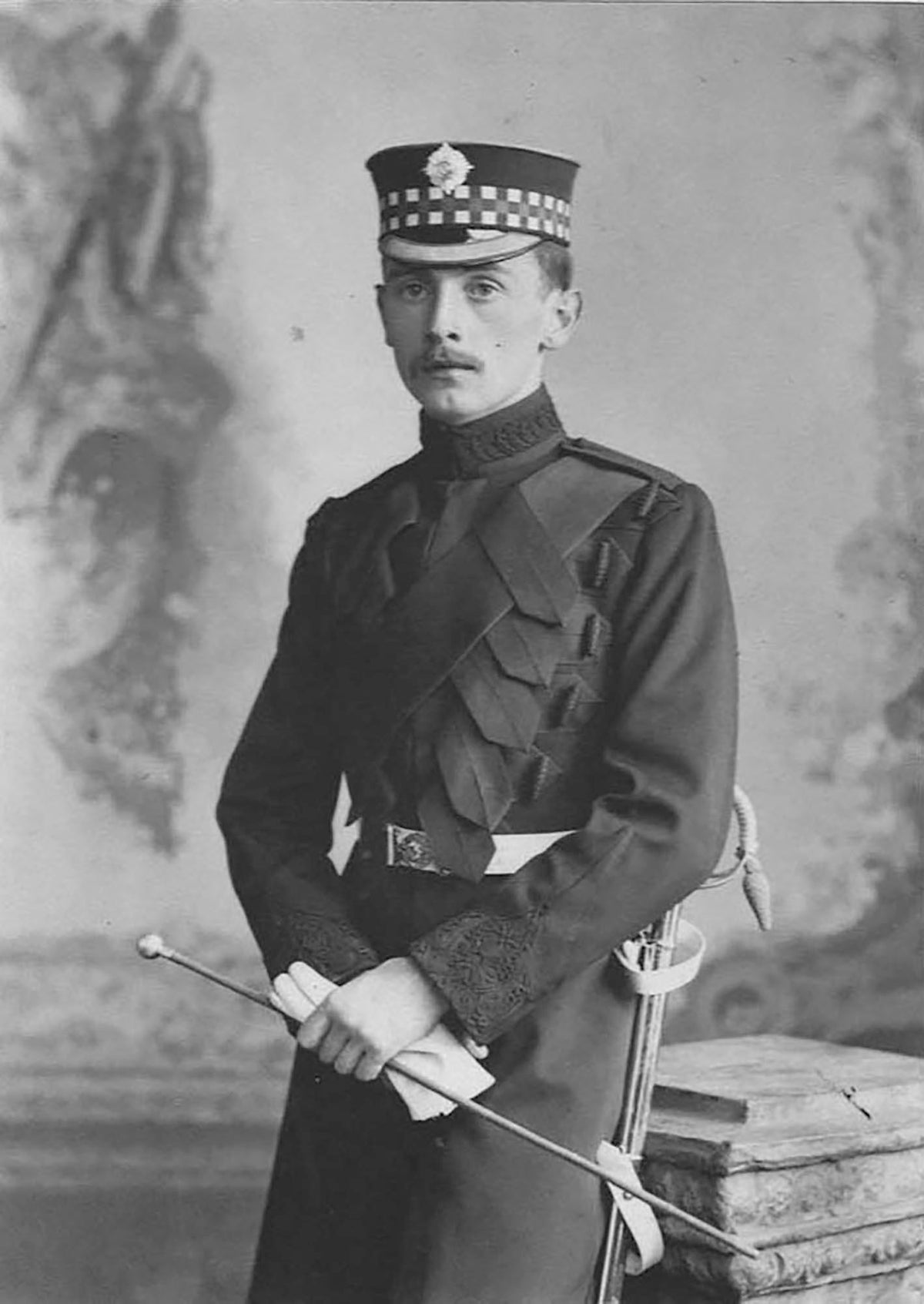

John Thorpe of Coddington Hall went from Eton to Sandhurst to a commission in the Scots Guards. During 11 years of service he fought in the South African or Boer War. There he received for gallantry the Victoria medal with six bars and the King Edward medal with two bars. On the death of his father in 1902 he retired from active service to manage the Coddington and Ardbrecknish estates and the family business in Newark.

In 1904 he married Cecilia Meade, a niece of the Earl of Clanwilliam. Three children followed swiftly. As an officer on the reserve list he transferred to the Sherwood Foresters Yeomanry advancing to the rank of Major and commanding a squadron.

However when war was declared in 1914 he returned to the Scots Guards reverting to his active service rank of Captain. Of this return Walter Batten Powell subsequently wrote:

“I have always thought it was most gallant of him after being away from infantry work so long going back to his old regiment, also forfeiting senior rank which he would have had with the Yeomanry. We shall all miss him most fearfully.”

At Loos in November1915 he displayed great coolness and courage in holding a position over three days of sustained German attack. In this engagement he was wounded and subsequently awarded the Military Cross For a later act of gallantry he was Mentioned in Despatches. Twice more he was hospitalized for shrapnel wounds, one to his hand and another passing through his shoulder without touching the bone. On a separate occasion he was in hospital with pneumonia.

Losses of all ranks serving in the Brigade of Guards were particularly heavy with two consequences for him. First his opportunity for leave and return to Coddington were curtailed. Second he was frequently required to take command of the company when the Senior officers were either killed or wounded in the action. Later he was appointed second in command of his battalion.

Husband and wife wrote almost daily. The majority of his letters from France have survived but none of hers to him. The postal service, even to the trenches in the line, was astonishingly effective. But all his correspondence had to pass through the censor’s office which resulted in a laconic style that forsook descriptive detail. His last letter to his wife at Coddington was dated 13th September 1916.

On the 15th September he was involved in heavy fighting all day as he led the battalion forward to take the Southern end of a prominent ridge halfway between Ginchy and Le Bonef. The crest of the ridge was the German defensive line and only at the right hand end were German troops still holding out in shell holes and isolated trenches. His day had started at dawn as he led his battalion through what Corporal Murray described as:

“One of the fiercest shell fires we had up to then experienced. There was many a moment when the shells would hide our Captain from us then clear away and leave us wondering if we had ever seen such bravery”.

During the advance he sustained a flesh wound to his arm but only halted to send his soldier servant, Private Miles, back from the front to the transport depot to get food. The pass he wrote on a scrap of paper to authorize the mission survives. In the absence of Private Miles it was Corporal Murray who was at his side as he led the advance up a communication trench towards the forward slope where some of our troops were already established. Second in command was Captain Stirling. He later wrote:

“There was a lot of firing and John was shot and killed instantaneously through the throat by a bullet fired at short range.”

This was at the hour before dusk and Corporal Murray saw him fall. He describes the scene:

“Acting Sergeant Major Clark who was at his side stopped to attend to him but we had to go on as the enemy were still coming on. It was almost half an hour later when I got the chance to go and see how he was that I found Captain Thorpe lying dead with Sergeant Major Clark lying dead a few yards away. There was nothing we could do so we carried him back to our dressing station. We got relieved that night so we carried our Captain’s body back out of range of the guns. He was buried the following afternoon in the Guards cemetery.”

The cemetery was at the village of Carnoy some ten kilometres South East of Albert. The burial was with the Pipe Band and full military honours.

What did his comrades say of him? Here is Captain Stirling:

“I miss old John so much: he had the happy habit of calmness- when things called most loudly for irritation- I never saw him worry or heard him grumble and there are few such.”

Then Private Miles:

“RF Company have not forgotten their late Captain nor will they for he loved them too much and as they speak of him they always speak of him as a ‘Father to the Company’. They mourn his loss very much.”

Private Miles was twice mentioned in letters posted to Coddington. On the first occasion John wrote:

“I have an exceedingly good soldier servant.”

In the second letter he describes him as “a perfect treasure.”

On the 13th October 1916, not quite a month after his death a service was held at Holy Trinity, Sloane Street:

”In memory of the officers, non-commissioned officers and men of the Scots Guards killed in action in France, during the recent fighting on the Somme.”

The full congregation was led by the Prime Minister, Mr Asquith. The officers were listed on the service sheet. They were 14 in number. Heading the list was Captain J. S. Thorpe MC. That was because at the date of his death he had served on the active and reserve lists for 23 years. He was commissioned at 20 and was 43 at the time of his death.

There were more permanent memorials. The Newark Advertiser on 1st May 1918 carried a full report of the service at the unveiling of his memorial in Coddington Church on 28th April. At much the same time the Bishop of Argyll and the Isles dedicated the granite cenotaph in his memory at the door of the church at Ardbrecknish which his father had built and which was accordingly dedicated to St. James.

(Contributed by Sir Mathew Thorpe, John Somerled Thorpe’s Grandson)

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Australian WWII Owen MK1 Machine Carbine SMG Custom Fabricated Replica with Sling Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armoured Fighting Vehicles of the World: AFVs of World War One (Hardcover Book) New Made Items

Uncategorized

Angolan Rebel 1970s era 60mm Inert Display Mortar from Angolan Civil War Original Items

Uncategorized

Armored Burgonet Helmet & Polearm from Scottish Castle Leith Hall Circa 1700 Original Items

Uncategorized

Band of Brothers ORIGINAL GERMAN WWII Le. F.H. 18 10.5cm ARTILLERY PIECE Original Items