Original British WWI Manchester Regiment Souvenir Leather Belt with Attached Buttons, Badges & Insignia Original Items

$ 195,00 $ 78,00

Original Item: One-of-a-kind. American soldiers were known for their love of souvenirs in the Great War; So, a lot of material history of the war came across the Atlantic with returning soldiers. Among collectors of military memorabilia from World War One “SOUVENIR BELTS” are items of interest.

German soldiers’ leather belts, and other belts from participating armies, that were festooned with buttons from soldiers uniforms are called Hate Belts / Souvenir Belts / Grave Digger Belts. These made for excellent collector’s pieces.

“Hate Belt”: the idea was that if a German soldier had killed or captured an Allied soldier, then he would have the button from the newly deceased or captured soldier attached to his belt as a kind of notch of conquest on his belt. This, no doubt, is the most intriguing explanation for those decorative belts.

“Souvenir Belt”: this description is apt for many of the belts that are in circulation today. The souvenir belt would involve a German infantryman’s belt being decorated with buttons and tabs from troops BOTH Allied and CENTRAL Powers and kept as a remembrance of The War.

“Grave Digger Belt” description is self explanatory, to a degree. Troops burying dead soldiers would sometimes remove buttons from those they buried as a remembrance. It is impossible to determine the origin of most belts, but some of these highly collectible belts provide some hints as to their origin. Nevertheless, these belts provide for excellent points of interest for collectors.

This example offered in good condition features a brown leather belt with a 2 rectangular brass buckles, most likely British private purchase. It features an impressive group of items in total attached to it, secured by a mixture of split pins, safety pins, and leather stripping. A few are installed via their own attachment tabs. Most look to be British forces regimental badges from various units, with some other insignia. The center of the belt is painted in white paint

MANCHESTER

56-09

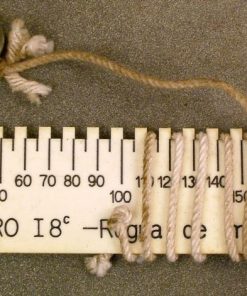

The belt measures about 29 inches long and 1 1/4 inches wide.

The 1st Battalion moved to France, landing at Marseille in September 1914.

The 2nd Manchesters embarked for France with the 5th Division in August 1914 and contributed to the rearguard actions that supported the British Expeditionary Force’s (BEF) retreat following the Battle of Mons.

On 1 July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, the regiment had nine battalions committed, including the Manchester Pals, the 16th (1st City), 17th (2nd City), 18th (3rd City) and 19th (4th City), all serving in the 90th Brigade of the 30th Division. The day proved to be the deadliest in the British Army’s history, with more than 57,000 killed, wounded or missing.

The regiment continued its involvement in the Somme Offensive. In late July, the 16th, 17th and 18th Manchesters attacked an area in the vicinity of the small village of Guillemont. During the action, Company Sergeant-Major George Evans, of the 18th, volunteered to deliver an important message, having witnessed five previous, fatal attempts to do so. He delivered his message, running more than half a mile despite being wounded. He was awarded the Victoria Cross.

C Company, 2nd Manchesters taking the battery at Francilly Selency. Painting by Richard Caton Woodville (1856–1927)

On 2 April 1917, the 2nd Manchesters attacked Francilly-Selency, in which C Company captured a battery of 77 mm guns and a number of machine-guns. Two paintings were made of this action by the military artist Richard Caton Woodville.

Preparations for a new offensive, the Third Battle of Ypres, in the Ypres sector had got under-way in June with a preliminary assault on Messines. The Manchester Pals’ Brigade fought in the offensive’s opening battle, at Pilckem Ridge, on 31 July.

In March 1918, the German Army launched an all-out offensive in the Somme sector. Faced with the prospect of continued American reinforcement (who had entered the war in April 1917) of the Allied armies, the Germans urgently sought a decisive victory on the Western Front.

The later-prominent war poet, Wilfred Owen served with the 2nd Battalion, Manchesters in the later stages of the war. On 1 October 1918, Owen led units of it to storm a number of enemy strong points near the village of Joncourt. For his courage and leadership in the Joncourt action, he was awarded the Military Cross, an award he had always sought in order to justify himself.

Middle East

In September 1914, just before the Ottoman Empire entered the war on Germany’s side, six of the regiment’s battalions joined the Egypt garrison.

The Manchesters disembarked at “V” and “W”,

During the Battle of Krithia Vineyard, the Manchesters suffered heavy losses and gained a Victoria Cross for gallantry by Lieutenant Forshaw of the 1/9th Battalion. The evacuation of Cape Helles lasted from December 1915 to January 1916. The Manchester battalions suffered many casualties during the Dardnalles Campaign. At the Helles Memorial, 1,215 names of the Manchesters alone fill the memorial.

The 1st Manchesters embarked for the Mesopotamian campaign, accompanying the infantry element of the Indian Corps, from France in late 1915. The battalion took part in the Battle of Dujaila in March 1916, which was intended to relieve the British forces in Kut-al-Amara, which was being besieged by Ottoman forces. In the battle, the 1st Manchesters seized the trenches of the Dujaila Redoubt with the 59th Scinde Rifles (Frontier Force); however, they were subsequently displaced by an Ottoman counter-attack, being forced back to their starting lines. During the withdrawal, Private Stringer held his ground single-handedly, securing the flank of his battalion. He was awarded the Victoria Cross. British and Indian forces suffered 4,000 casualties. After five failed attempts to relieve the town, Kut surrendered to Ottoman forces on 29 April 1916. The 1st Manchesters would take part in further actions in Mesopotamia, but in March 1918 the battalion moved to Egypt.

The battalion then moved to Ottoman-controlled Palestine, still part of the 3rd (Lahore) Division, to take part in the campaign there against the Ottomans. They fought in the last major offensive there, at Megiddo, on 19 September. Within three hours the Turkish lines, held by the Turkish Eighth Army, had been broken. Open warfare defined the theatre. During the Megiddo offensive, the cavalry advanced more than 70 miles in 36 hours. The 1st Manchesters took part in further engagements until the Armistice with the Ottoman Empire, remaining in the area until 1919.

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Australian WWII Owen MK1 Machine Carbine SMG Custom Fabricated Replica with Sling Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armored Burgonet Helmet & Polearm from Scottish Castle Leith Hall Circa 1700 Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Angolan Rebel 1970s era 60mm Inert Display Mortar from Angolan Civil War Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized