Original British Pre-WWII Schermuly Pistol Rocket Apparatus Rescue Line Thrower Set in Case – Serial No 60510 Original Items

$ 1.195,00 $ 298,75

Original Items: Only one set available. William Schermuly 1857-1929 was one of fathers of modern rocketry. He had served aboard vessels at sea and knew of how many lives were lost each year due to shipwrecks. He invented several different line throwing devices, some of which were used in WWI for such things as throwing telephone lines from trench to trench while under fire. But, the British Admiralty still didn’t see a need for his line throwers. Finally, he came up with a design that was small, easily aimed and fired, accurate and simple to use – the Schermuly Rocket Pistol Apparatus. In 1929, just 19 days before he died, the Admiralty made it compulsory for all vessels over 500 tons to carry line throwers. It was so successful that in 1938, a new act made it a requirement for all ships over 80 tons or 50 feet in length.

The pistol is based on the Webley & Scott brass flare pistol, with a steel barrel extension to take a rocket that would propel a wire over distance. The wire could be attached to a cable to help transfer people from ship to ship or shore to ship.

The pistol barrel has an extra handle to steady the gun when firing. The wood grips are made of mahogany.

Dating from the 1920s this Schermuly Line Throwing Rocket Pistol has a brass frame and chamber, while the rocket tube, or barrel, is steel. It has mahogany grips and a ribbed Bakelite secondary handle, and there are British proof marks on the chamber and frame. It is also marked with serial number 60510 on the barrel and frame, and has ;the SCHERMULY’S PATENT information on the left side of the frame. Overall, the pistol is in very good condition.

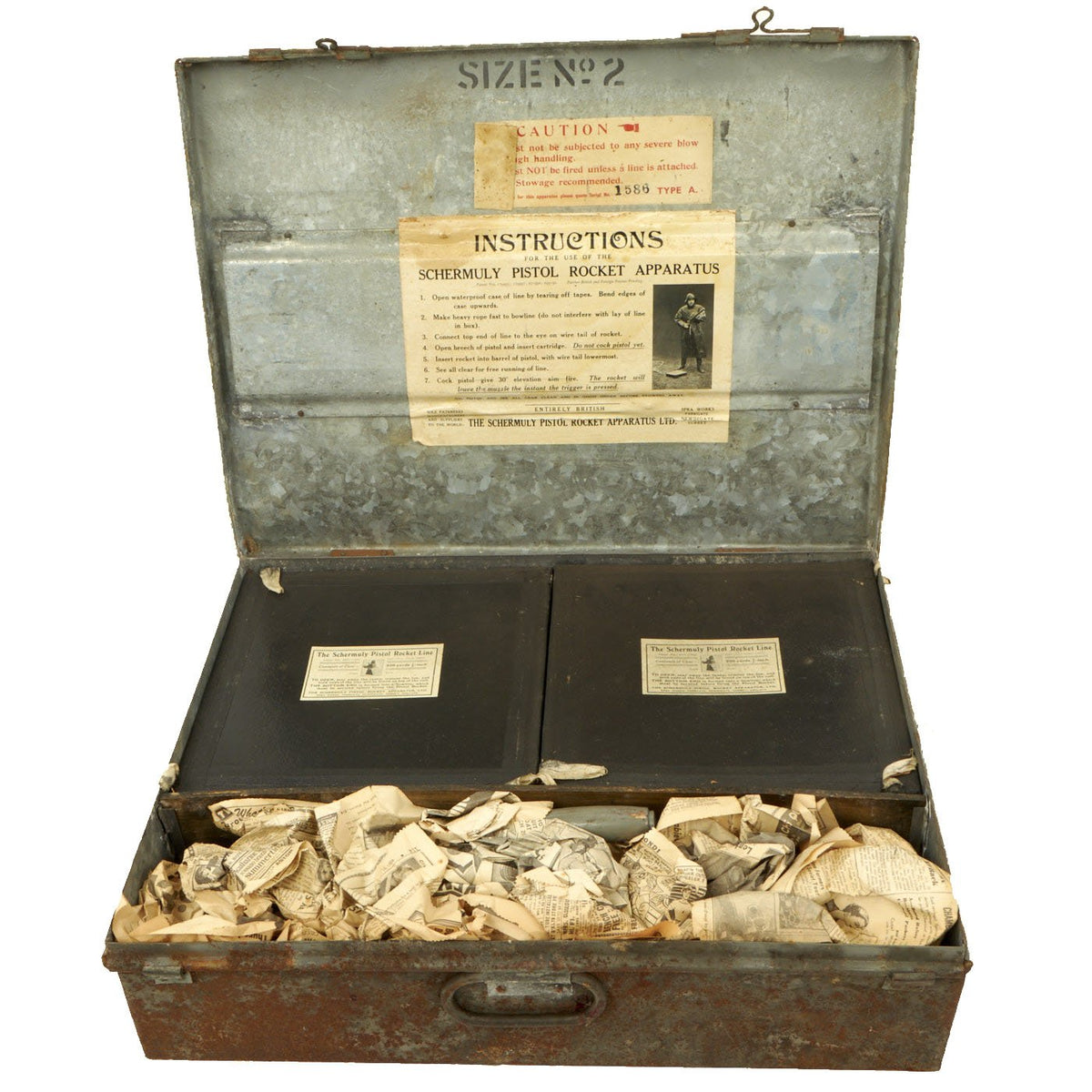

Also included is the tin case which measures approximately 19″ x 7″ x 25″ which is complete with 4 unopened boxes of 250 1/2 inch line, 4 deactivated rockets, a tin of 5 deactivated cartridges, original instruction label and more! This is a set that was issued but never used. Found in a warehouse on the Northeastern Seaboard of the United States where it has laid undisturbed for over 100 years!

This pistol set represents a very unique piece of nautical history, and would complement any collection of nautical or WWII artifacts.

The Schermuly Pistol Rocket Apparatus by Joel R Kolander

If a firearm is unusual enough, it enters into that special place of “curiosa”: the Gyrojet, harmonica guns, duckfoot pistols, cane guns, and on and on. One of those guns that isn’t unusual in its appearance, yet performs its task in an unusual manner is the Schermuly Line Throwing gun. Made in a “pistol” form, it was a smaller, lighter, simpler form of a line thrower allowing them to be used more widely and practically. In the nearly half-century prior, ships that had foundered or run aground had very few options.

The leading option was a short cannon of sorts, known as the Lyle Gun, which fired a 19-pound tethered projectile that sat on the muzzle. Lines were necessarily light to achieve maximum distance, and were often used to establish larger, sturdier lines. Named for their inventor, West Point and MIT graduate First Lieutenant David A. Lyle, these guns were heavy, experienced massive recoil, and used a special type of blackpowder, making them a welcome rescue tool though difficult and cumbersome to use. For his contributions, most line throwing guns are known as “Lyle guns” to this day.

To drive the point home of how important this invention was, ships during this time were still dependent on sail or steam for power, and commonly ran aground. Lodged in mud, sand, or rock, especially during a violent storm, is a poor place to be, and ships could be broken up quickly. A team of volunteer “surf men” sometimes had only hours to arrive on scene, often during nightmarish weather conditions, and perform a sea rescue from the beach. It is a terrifying thought to be so close to shore, but trapped aboard a ship disintegrating with every crash of the waves. Dubbed Lyle’s Life Saving Gun, it was a very important contribution to sea-faring communities, especially in a time when much trade and travel was conducted via waterway. From its inception circa 1878 to the early 20th century, the Lyle gun was an effective naval tool. The fact that it remained in production through World War II is further testament to its reliability and necessity.

The leading option was a short cannon of sorts, known as the Lyle Gun, which fired a 19-pound tethered projectile that sat on the muzzle. Lines were necessarily light to achieve maximum distance, and were often used to establish larger, sturdier lines. Named for their inventor, West Point and MIT graduate First Lieutenant David A. Lyle, these guns were heavy, experienced massive recoil, and used a special type of blackpowder, making them a welcome rescue tool though difficult and cumbersome to use. For his contributions, most line throwing guns are known as “Lyle guns” to this day.

To drive the point home of how important this invention was, ships during this time were still dependent on sail or steam for power, and commonly ran aground. Lodged in mud, sand, or rock, especially during a violent storm, is a poor place to be, and ships could be broken up quickly. A team of volunteer “surf men” sometimes had only hours to arrive on scene, often during nightmarish weather conditions, and perform a sea rescue from the beach. It is a terrifying thought to be so close to shore, but trapped aboard a ship disintegrating with every crash of the waves. Dubbed Lyle’s Life Saving Gun, it was a very important contribution to sea-faring communities, especially in a time when much trade and travel was conducted via waterway. From its inception circa 1878 to the early 20th century, the Lyle gun was an effective naval tool. The fact that it remained in production through World War II is further testament to its reliability and necessity.

Obviously there was room for improvement, and that was not lost upon William Schermuly – a former seaman who was later quite involved in the pioneering of modern rocketry. A tremendous swimmer, a fighter, and an adventurous spirit, the man did not lack for courage, nor the vocabulary of an old salt, once describing himself as “an old blue water windjammer shellback” (translation: a sailor who went out into deep ocean on the largest sailing cargo ships and crossed the equator). After leaving the sea in 1880, he of course had a soft spot for the men who still earned their living there and often risked their lives.

His first observations involved the “surf crews” and their inherent faults. For example, successfully firing a cannon from shore at a ship required a great deal of skill and aiming, let alone attempting to do so during a squall. Furthermore, firing was often done into the winds, which shortened the devices’ effective range and made precise aiming more difficult still. Also, ships were often dependent on the surf crews for rescue. Usually comprised entirely of volunteers, the crews, while brave, often lacked training or expertise with equipment such as the Lyle gun. Not to mention, that crews were not available in every town. To be rescued, one would pray they had just beached next to a town with such a crew that was also equipped with a Lyle gun.

Schermuly surmised that to remedy these short-comings, a lifeline could instead be fired from the vessel. After all, aiming for shore requires much less precision than aiming for a boat, and lines fired inland might even be aided by the wind and enjoy a greater range. Besides, ship-borne lifesaving devices could also be used from ship to ship while at sea. However, to equip each ship with a Lyle gun or similar device would prove exceedingly expensive and take up space and weight, two precious commodities on a fully crewed cargo ship. The device would have to be inexpensive, reliable, compact, and easy to use even in the worst of conditions. Of course, Schermuly also saw rockets as part of the solution.

By 1887 he was developing ideas for ship-based rescue lines, and by 1897 he was exhibiting his Schermuly life saving rocket at Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee Exposition and winning the gold medal to boot. Carried in a case along with its rope and launcher, this looked like a giant, mounted bottle rocket and unfortunately, utilized a cardboard-type paper case. Still, the unit was compact, easy to set up, and is said to have a range of approximately 285 meters. Schermuly also developed a way to better lay the line inside the case (called “flaking” the line) so that it would feed more easily and reliably while taking up less space. Following his lead, numerous ship-borne devices became available to save grounded ships, but they were inaccurate, prone to water damage, complicated, or worse.

Despite his success at the exposition, Schermuly saw virtually no interest in his invention. This was particularly demoralizing for a man quoted as saying, “Lost ships can be replaced, but lives are gone forever.” He was ignored by the powers that be of the British Navy and numerous other sources, largely due to the additional cost of outfitting ships with the new rockets. This period of numerous rejections and disinterest, he dubbed, “his heartbreak years.” Eventually, early adopters began to step forward. In 1912, the Royal Mail Steam Packet utilized Schermuly rockets and others would follow. Robert Shackleton outfitted one on the Endurance, and other famous explorers gave their glowing endorsements. It was only after the SS Rohilla sank after hitting a mine in 1914 that the British Admiralty placed their first order for Schermuly rockets to be placed aboard troop and hospital ships. During the Great War, the Canadian Army even began using them to throw telephone lines from trench to trench to avoid exposing troops to enemy fire. There are also stories of attaching a grappling hook of sorts to it and firing it over barbed wire so that it could be more easily pulled away. This slow introduction into commercial and military markets earned much confidence in the rockets, and by 1922, their use was prolific. To meet demand Schermuly brought his three grown sons into the business. However, it was not enough. William Schermuly still envisioned a simpler device that eliminated faults in his design, which was not very durable, prone to cross winds, and took 5-10 seconds to ignite.

To improve his rocket powered line thrower, many issues that plagued early rocketry students arose. It had to be large enough to carry adequate propellant but not large enough to excessively increase the weight or be effected too much my wind. A line firing gun, as opposed to a rocket, would take care of many of his issues: it fired instantaneously and made aiming easier, its projectiles would be less effected by wind and less prone to water damage. However, a gun also introduced recoil, a bad thing on the deck of a wet ship, and to achieve a distance equal to that of a rocket required a massive powder charge that often risked breaking the line. Not to mention that Schermuly also saw immense benefit in the visibility of a rocket being fired toward shore. The fire plume and smoke trail made the line easy to find for the rescuing surf crews. So he did what anyone would do – took the best of both inventions and combined them.

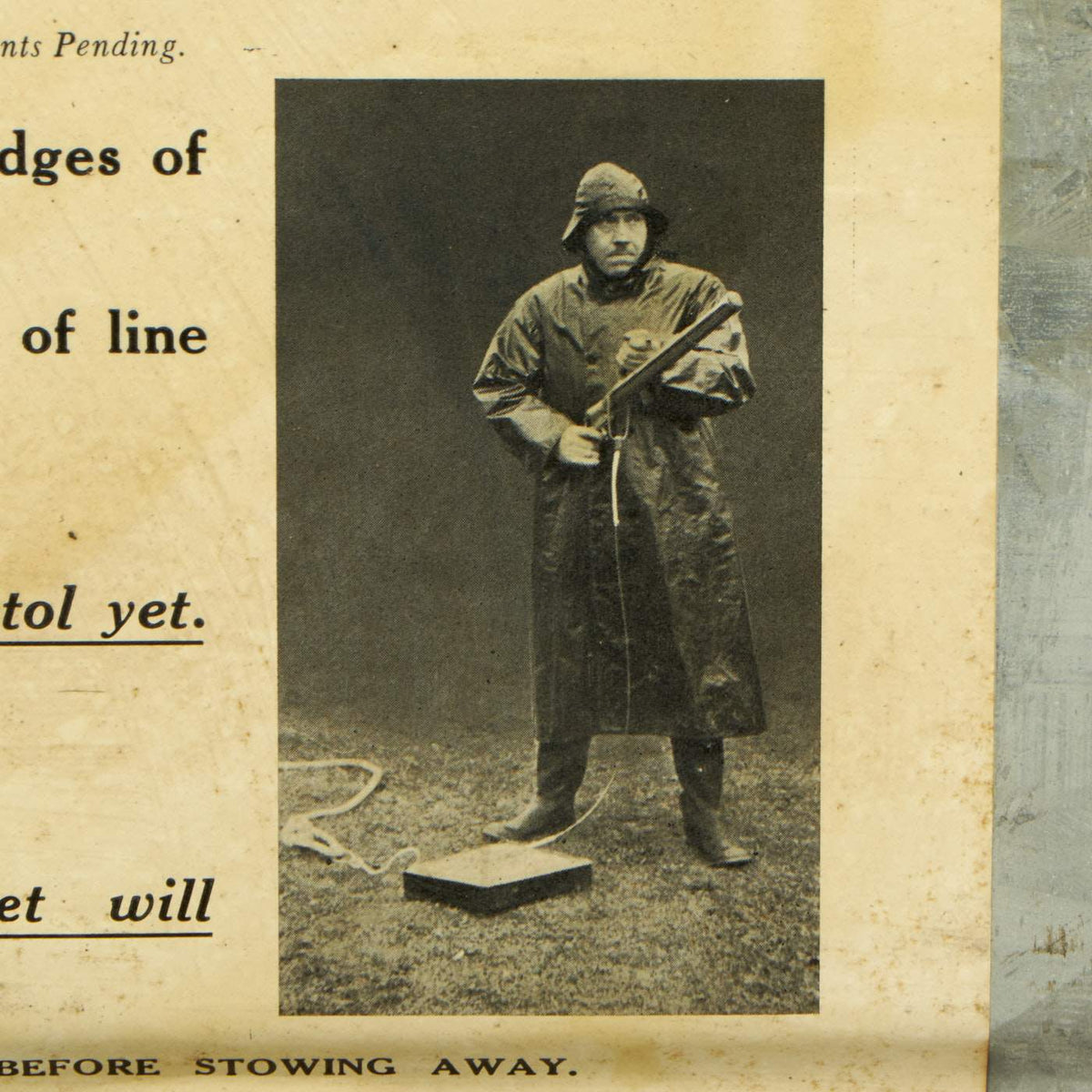

The new apparatus would utilize the quick-firing, weather-proof projectile less effected by wind, as well as the far-traveling, easy-to-see, virtually recoilless rocket that wouldn’t snap the lifelines. But how to achieve all this? Schermuly selected a pistol sized firing device for its size, slapped a long barrel on it, and used the gases of a pistol-style cartridge (essentially a blank round) to eject the rocket from the barrel, penetrate the water-proof disc at its base, and ignite the propellant of now smaller, steel cased rocket. Long story short, it worked. In fact, it worked so well that Schermuly’s grandson was often used in its firing demonstrations at only 8-years old. The Schermuly Pistol Rocket Apparatus (SPRA) was born and immediately began outperforming the competition, often doubling or tripling the distance of other ship-to-shore systems and demonstrating numerous advantages of old shore-to-ship systems such as the Lyle gun. It didn’t take long before the British Admiralty was eating crow and the SPRA was adopted into the standard equipment aboard the Royal Navy.

By 1926, the Schermuly Pistol Rocket Appartus, Ltd. took form, and the family business could now produce their own device to their own satisfaction. Within a year the business was stable. Twenty-two different shipping lines were using his rockets, and by 1929, the Merchant Shipping Act mandated that “Every British ship exceeding five hundred tons… when going to sea from any port in the United Kingdom shall be provided with a line-throwing appliance approved by the Board of Trade.” Nineteen days later, Schermuly died. His life’s work complete, he saved thousands of lives at sea, contributed to the seafaring life he loved so dearly, and fought successfully for new legislation to save even more lives.

Schermuly’s invention didn’t just disappear with the glory days of the British Empire. It was reborn many times with the demands of the Second World War. His rockets would propel grapnel hooks, which were used by U.S. Rangers on D-Day. Kite launching rockets deployed emergency radio aerial antennae. There were numerous signal flares, various uses for projected lines, and perhaps most pleasing to the inventor, several ways to aid seamen in peril on the sea, such as lifeboat distress signals and self-inflating life rafts that automatically fired rocket propelled lines into the water so that the crew could pull themselves aboard. Line throwing guns are still used to this day in the commercial and military sectors, and the Schermuly name remains closely tied to parachute flares.

When water-based transportation and shipping was so prevalent and important, the impact of his life saving devices cannot be overlooked, no matter how easy it may be do so in a modern world where that technology has largely been replaced. Firearms with fascinating histories such as this abound in our firearms auctions, and the 2018 June Regional Firearms Auction is no exception. Please search through our online catalog today and find your own piece of military or maritime history.

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Australian WWII Owen MK1 Machine Carbine SMG Custom Fabricated Replica with Sling Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armored Burgonet Helmet & Polearm from Scottish Castle Leith Hall Circa 1700 Original Items

Uncategorized

Angolan Rebel 1970s era 60mm Inert Display Mortar from Angolan Civil War Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armoured Fighting Vehicles of the World: AFVs of World War One (Hardcover Book) New Made Items

Uncategorized