Original British Post WWI P-1903 Five Pocket Leather Cavalry Bandolier by Barrow Hepburn & Gale – dated 1922 Original Items

$ 195,00 $ 78,00

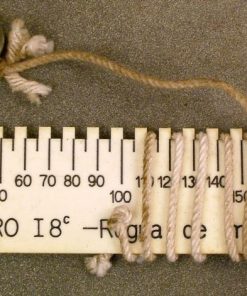

Original Item: Only One Available. Designated the “Bandolier for Mounted Cavalry P-1903”, this is a high quality leather bandolier with five leather pockets, each designed to carry two 5 round stripper clips of .303 caliber Ammunition. This example is maker marked and dated between the buckle and 1st pocket with:

BARROW HEPBURN & GALE LTD.

LONDON

1922

Interestingly, there is also an H.G.R. 18 marking right by the buckle, for Hepburn Gale & Ross, the name of the company before it merged with Samuel Barrow and Brother to become Barrow, Hepburn & Gale. This may mean that it was manufactured late in WWI, and did not see service, and then was reissued and stamped with the new name of the company when it was finally needed.

The bandolier looks to originally have been issued in brown leather, and was then dyed or refinished in black, possibly by the manufacturer. There is some wear through in the finish that shows this. The bandolier looks to be fully intact, with all buckles and studs functional and included. As with any leather good of this age, it is a bit dry and should be handled with care.

Definitely a very nice example and ready to display!

The 2nd Boer War is over, and the limitations and deficiencies of the Valise Equipment, Pattern 1888 are well known. Everyone agrees that a replacement is needed and the Mills Woven Cartridge Belt Company of London, England, is eager to step in with its latest web equipment. The War Office, though, has other ideas, and when the new equipment is chosen, it is still a leather equipment, rather than cotton webbing. This new equipment was the Bandolier Equipment, Pattern 1903.

According to Albert Lethern, author of the M.E.Co.. Golden Jubilee book, the choice of leather over Mills’ web was made because of a misunderstanding by the General Staff . During the war, the Mills Company had produced cheap, “single use” ammunition bandoliers made of very light woven webbing. The intention was solely for ammunition re-supply, cartridge pouches being re-filled and the bandolier discarded. In practice, these bandoliers were issued for wear by the growing numbers of Mounted Infantry then being deployed.. Because of their very light construction, the cartridge sleeves stretched and the reloaded cartridges enthusiastically flung themselves in all directions. Denys Reitz, in his book Commando, describes how he and his comrades followed the columns of soldiers. Along the route and wherever the Brits had halted, plenty of lost ammunition could be picked up by the Boers, who were using captured Lee-Metford rifles This misuse, from the Mills Company’s viewpoint, prejudiced field commanders against all webbing. Amongst the “hide bound officialdom” (to use Lethern’s oh-so-appropriate phrase), who gave damning reports against web, were Generals French, Plumer, Baden-Powell, Lord Roberts, and Lord Kitchener himself.

This problem was known at the time and instructions were issued to modify the heavier web waistbelts, which were actually being used as bandoliers. Leather (sometimes fabric) flaps were stitched along the top edge, secured to brass studs. M.W.C.B.Co. also re-designed the heavier bandoliers to have a continuous web flap. However, mud had been thrown and it had stuck, at least in the minds of senior officers. The damage had been done.

What does seem clear is that the Pattern 1903 equipment wasn’t very good, at least as an infantry equipment. It had all of the old problems of Slade-Wallace: it was uncomfortable to wear, time consuming to put on and off, and the items being carried were not easily accessible in the field. The period between the Boer War and 1914 was little-photographed and, within five years, the Regular Army were re-equipping with Pattern 1908 Web Equipment. Bandolier Equipment was used to upgrade units of the Territorial Force, all of whom had been previously equipped with leather equipment of earlier patterns. Judging from contemporary photographs of the Great War, Pattern 1903 does not seem to have been terribly popular in the field. Probably the last widespread use of Bandolier Equipment was by a Territorial unit, the 1st/5th Lancashire Fusiliers, who landed in Gallipoli, as shown in the photograph on the right. The Pattern did continue in use in the Great War, with Colonial units, campaigning in Africa and also many of the Indian Army units on the Western Front.

For use by the cavalry, though, it seems to have been much more acceptable. M.E.Co.’s cavalry webbing of 1911 underwent military trials, and by 1914 General Sir John French had recommended it for adoption. The onset of war, though, prevented that from happening, and Pattern 1903 continued in use as a cavalry and second line equipment. Although the entire equipment does not seem to have been overly popular, the Bandoliers themselves, especially the five pocket version, are commonly seen in period photographs. They had become the distinguishing mark of the mounted soldier. Thus Drivers of the Corps of Royal Engineers also wore Bandoliers, but of the 50-round type, whereas cavalrymen all wore the 90-round version. In 1922, Ireland separated into the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland, or Ulster. Many of the 50-round Bandoliers were dyed black and issued to the newly formed Royal Ulster Constabulary, along with other items from the Pattern. The 50-round Bandolier was produced as late as WWII in South Africa.

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Australian WWII Owen MK1 Machine Carbine SMG Custom Fabricated Replica with Sling Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Angolan Rebel 1970s era 60mm Inert Display Mortar from Angolan Civil War Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized