Original British Georgian Officer’s Saber with Walrus Bone Hilt Inscribed to Lt. Col. Alexander Hamilton – 30th Reg’t of Foot – Served at Quatre Bras and Waterloo Original Items

$ 5.995,00 $ 1.498,75

Original Item: One-of-a-Kind. Here we have a fine P-1796 wide bladed Officer’s Cavalry Saber, with a very curved wide blade of 31″, now totally polished “in the white”. Holding it in the light however shows it to have originally been covered in engravings of Military trophies, Coats of Arms, and probably also a “fire blued” finish on part of it. Unfortunately the year and cleaning have removed all of this.

The hilt features the classic brass “P” shaped guard of the P-1796 saber, surrounding a grip of Walrus “ivory” bone that is bound with twisted gilt wire. It comes complete in its original brass mounted leather scabbard, engraved on the locket with:-

Lt. Col. Alexander Hamilton

30th Regiment Of Foot

The brass mounts of the sword and scabbard were probably originally gilt washed, however this is now all absent. A fighting Sword that has seen some real action. In lovely collectable and display condition.

ALEXANDER HAMILTON, 1765-1838 – A career Soldier, enlisted as Ensign in 1794. Saw action in Malta, EGYPT promoted to Major in 1804. Joined 30th Regiment of Foot in 1797. Joined Wellington in Portugal and fought at Battles of Fuentes and Salamanca in 1811 and 1812 . Promoted LT. COLONEL of 30TH Regt of Foot.

He served famously at QUATRE BRAS the day before WATERLOO and was very seriously wounded in the leg which by chance was not amputated. He even appeared at WATERLOO the following day and was recommended by Wellington himself for the COMPANION OF THE ORDER OF THE BATH awarded by KING GEORGE III two days later for his bravery. He died in 1838, another of England’s great heroes. Masses of Internet research available!

Specifications:

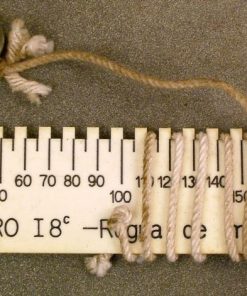

Blade Length: 30″

Blade Style: Curved Single Edge with Wide Fuller

Overall length: 34 3/4“

Guard: 6″W x 5″L

Scabbard Length: 30 1/4″

In 1796, the British War Department adopted a newly designed saber for use by the Light Cavalry. This included the Hussars, the Light Dragoons and the Horse (Mounted) Artillery. John Gaspard Le Merchant, a British cavalry officer, designed the saber based upon his military experiences in the field. Le Merchant saw the inadequacies in the British Pattern 1788 cavalry saber design, as well as the failure of the accompanying tactics, while he was serving as a brigade major with the British Cavalry in Flanders, during the Low Countries campaign in the early years of the French Revolutionary Wars (1793-1795). Upon returning to England, he enlisted the aid of English cutler and sword maker Henry Osborn (some references spell the name with an “e” at the end, but Osborn blades are not so marked) and between them was born the Pattern 1796 Light Cavalry Saber. The saber had a curved blade with relatively short, slashing tip, referred to by some as a “hatchet” tip. The blade was typically between 32 ½” and 33” long and had a simple stirrup shaped iron guard with a pair of languets on either side of the guard to “trap” an enemy’s blade. The grip had a grooved wood core, which was wrapped with braided cord and then wrapped with leather, without an exterior wrap of wire as was typical of many sabers of the era. A pair of iron “ears” extended down from the backstrap on either side of the grip’s center, and a transverse pin reinforced the grip to backstrap attachment; strengthening it and keeping the grip from wobbling or working itself loose from the hilt. Le Merchant’s design was strictly for hacking and slashing, and not for thrusting, as the Pattern 1796 Heavy Cavalry saber was intended.

Le Merchant credited the sword designs of the Hungarians, Turks and Moors for his inspiration to create a heavily curved blade that actually got wider near the tip. As the saber was designed and balanced for hacking and slashing at an enemy, it was the last 10” or so of the blade, nearest the tip that saw the most use in combat, and that usually shows the most use on extant examples. This area was often sharpened to a near razor like edge, and period accounts have been known to compare the effect of the 1796 Light Cavalry saber upon its enemy to meat being assaulted by a giant slicer! Le Merchant not only designed the saber, but also the accompanying tactics, and taught that the saber should be used to strike at the head and arms of enemy cavalrymen, rather than to thrust at them.

British cavalryman George Farmer, who was serving with the 11thRegiment of Light Dragoons during the Peninsular Campaign against Napoleon, recalled one account of the effectiveness of the P1796 in combat. During a skirmish with French cavalry on the Guadiana River, Farmer remembered:

“Just then a French officer stooping over the body of one of his countrymen, who dropped the instant on his horse’s neck, delivered a thrust at poor Harry Wilson’s body; and delivered it effectually. I firmly believe that Wilson died on the instant yet, though he felt the sword in its progress, he, with characteristic self-command, kept his eye on the enemy in his front; and, raising himself in his stirrups, let fall upon the Frenchman’s head such a blow, that brass and skull parted before it, and the man’s head was cloven asunder to the chin. It was the most tremendous blow I ever beheld struck; and both he who gave, and his opponent who received it, dropped dead together. The brass helmet was afterwards examined by order of a French officer, who, as well as myself, was astonished at the exploit; and the cut was found to be as clean as if the sword had gone through a turnip, not so much as a dint being left on either side of it.”

The design was so successful and well received that the Prussian Pattern 1811 Blücher Saber was a nearly direct copy of Le Merchant’s design, and sabers based upon the P1796 would serve German cavalry well into the 20th century, and even during the First World War!

The saber was carried in a heavy iron scabbard that was supported by a pair of mounts with a pair of suspension rings. Often the sabers and scabbards that saw service with the British military were rack numbered, and today mixed numbered scabbards and sabers are quite common, as the swords were more likely to be lost on the field than the accompanying scabbards, and a similarly retrieved battlefield pick up usually replaced the lost sword. The Pattern 1796 Light Cavalry saber remained in use with the British cavalry for only a few years after the battle of Waterloo (June 18, 1815), and was officially replaced with the Pattern 1821 Light Cavalry saber, although the effectiveness and the popularity of the P1796 with the troopers resulted in the saber remaining in service for several decades after its official “replacement”, even seeing service as late as the Crimean War with some units, despite having been superseded by two different patterns (both the Pattern 1821 and Pattern 1853).

Not long after the development and adoption of the Pattern 1796 Light Cavalry Saber, Osborn modified the blade to create an officer’s pattern of the sword. This blade was more traditional at the end with less of a hatchet tip. It was tapered and pointed sufficiently to allow the saber to be used for thrusting as well. As British officers were required to provide their own uniforms and sidearms, an amazing amount of latitude was granted to officer’s sabers. As long as the sword conformed to the basic pattern, embellishments were allowed, with the imagination and the pocket book of the buyers being the only major constraints on the design. After the adoption of the Lion Pommel design for the Pattern 1803 Infantry Officer’s Sword, this motif became a popular one to incorporate into Pattern 1796 Light Cavalry Officer’s Sabers. Lion hilt P1796 sabers were not uncommon during the first quarter of the 19thcentury. The blades often were often of a variety of curvatures and lengths, again often at the whim of the officer himself. While the steel scabbards were appropriate and necessary in the saddle, often leather scabbards were acquired as well as the metal ones for wear when not mounted.

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armoured Fighting Vehicles of the World: AFVs of World War One (Hardcover Book) New Made Items

Uncategorized

Armored Burgonet Helmet & Polearm from Scottish Castle Leith Hall Circa 1700 Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Angolan Rebel 1970s era 60mm Inert Display Mortar from Angolan Civil War Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized