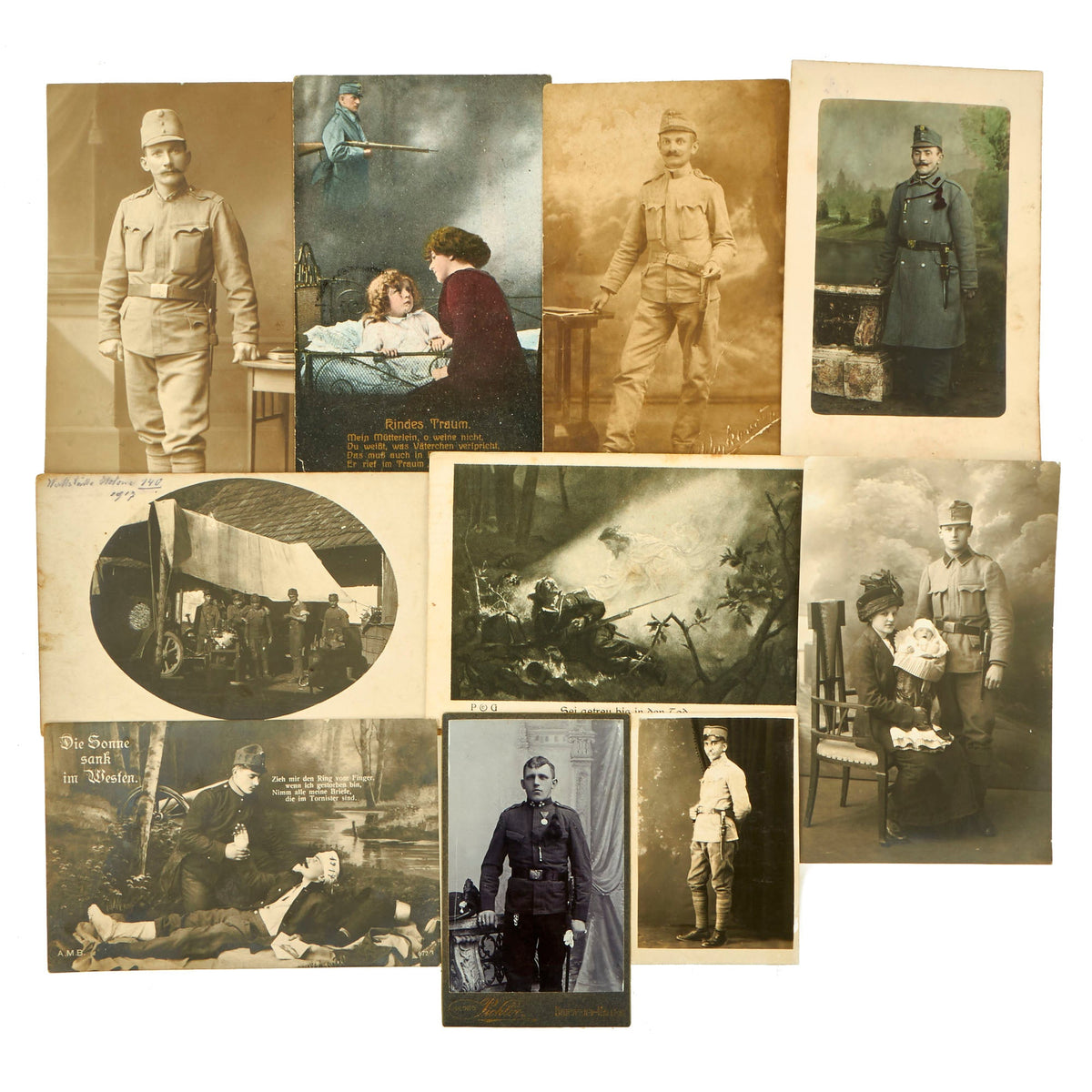

Original Austro-Hungarian WWI Photograph/Postcard Lot With Writing – 10 Photos Original Items

$ 125,00 $ 50,00

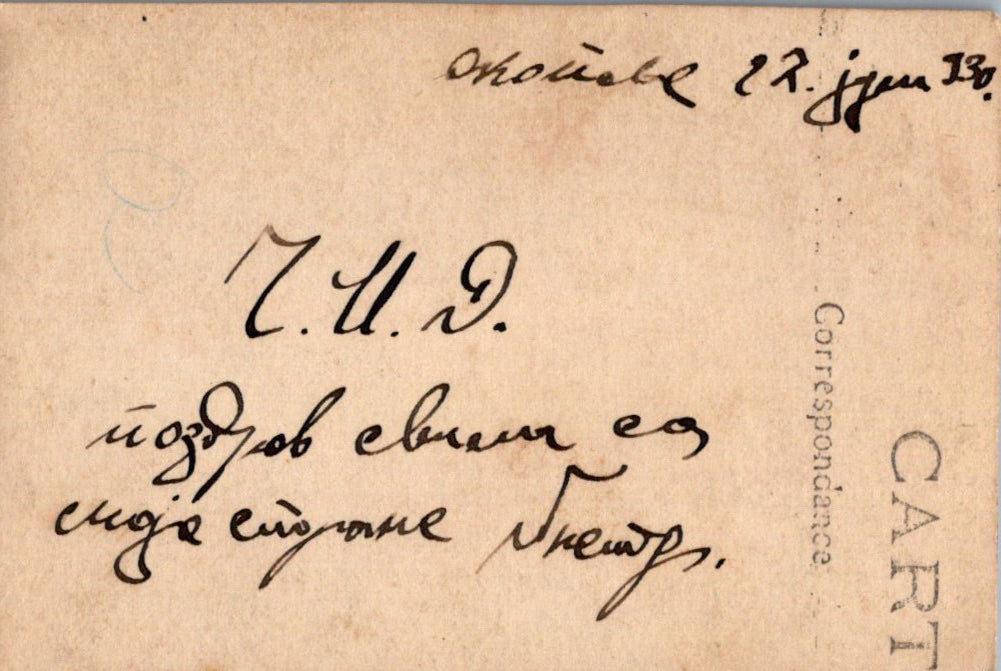

Original Items: Only One Lot of 10 Available. This is a lovely little photo grouping which in fact are actual postcards as well, a common practice seen both during WWI and WWII. The photographs feature similar images of soldiers either in the field or staged for a portrait indoors. A few of the cards have early mid-war dates as well as messages written on them, perfect opportunity to start a translation project and research. They are all in wonderful condition with the images still easily discernible and the writing mostly legible.

A lovely grouping ready for further research and display.

Austro-Hungarian entry into World War I

On 28 July 1914, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. Within days, long-standing mobilization plans went into effect to initiate invasions or guard against them and Russia, France and Britain stood arrayed against Austria and Germany in what at the time was called the “Great War”, and was later named “World War I” or the “First World War”. Austria thought in terms of one small limited war involving just the two countries. It did not plan a wider war such as exploded in a matter of days.

British historian John Zametica argued that Austria-Hungary was primarily responsible for starting the war, as its leaders believed that a successful war against Serbia was the only way it could remain a Great Power, solve deep internal disputes caused by Hungarian demands, and regain influence in the Balkan states. Others, most notably Christopher Clark, have argued that Austria-Hungary, confronted with a neighbor determined to incite continual unrest and ultimately acquire all of the “Serb” inhabited lands of the Monarchy (according to the Pan-Serb point of view included all of Croatia, Dalmatia, Bosnia, Hercegovina, and some of the southern counties of the Hungary (roughly corresponding to today’s Vojvodina), and whose military and government was intertwined with the irredentist terrorist group known as “The Black Hand”, saw no practical alternative to the use of force in ending what amounted to subversion from Serbia directed at a large chunk of its territories. In this perspective, Austria had little choice but to credibly threaten war and force Serbian submission if it wished to remain a Great Power.

The view of the key figures in the “war party” inside the Tsarist government and many military leaders in Russia, that Germany had deliberately incited Austria-Hungary to attack Serbia in order to have a pretext for war with Russia and France, promoted by the German historian Fritz Fischer from the 1960s onwards is no longer accepted by mainstream historians. One of the key drivers of the outbreak of war were two key misperceptions that were radically at odds: The key German decision-makers convinced themselves Russia would accept an Austrian counter-strike on Serbia and weren’t ready for or seeking a general European war, instead engaged in a bluff (especially because Russia had backed down in both earlier crises, in 1908, and again over Albania in October 1913); at the very same time the most important Russian decision-makers viewed any decisive Austrian response as necessarily dictated by and fomented in Berlin, and therefore proof of an active German desire for war with the Tsar’s Empire.

There was no serious joint planning with Germany before the war started–and little during the war itself, as leaders in Vienna distrusted German ambitions.

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armoured Fighting Vehicles of the World: AFVs of World War One (Hardcover Book) New Made Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Australian WWII Owen MK1 Machine Carbine SMG Custom Fabricated Replica with Sling Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armored Burgonet Helmet & Polearm from Scottish Castle Leith Hall Circa 1700 Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Band of Brothers ORIGINAL GERMAN WWII Le. F.H. 18 10.5cm ARTILLERY PIECE Original Items

Uncategorized