Original Anglo-Zulu War Battle of Rorke’s Drift Knobkerrie War Club Recovered by Sergeant George Smith, B Company, 2nd Battalion, 24th Regiment of Foot in 1879 Original Items

$ 3.495,00 $ 873,75

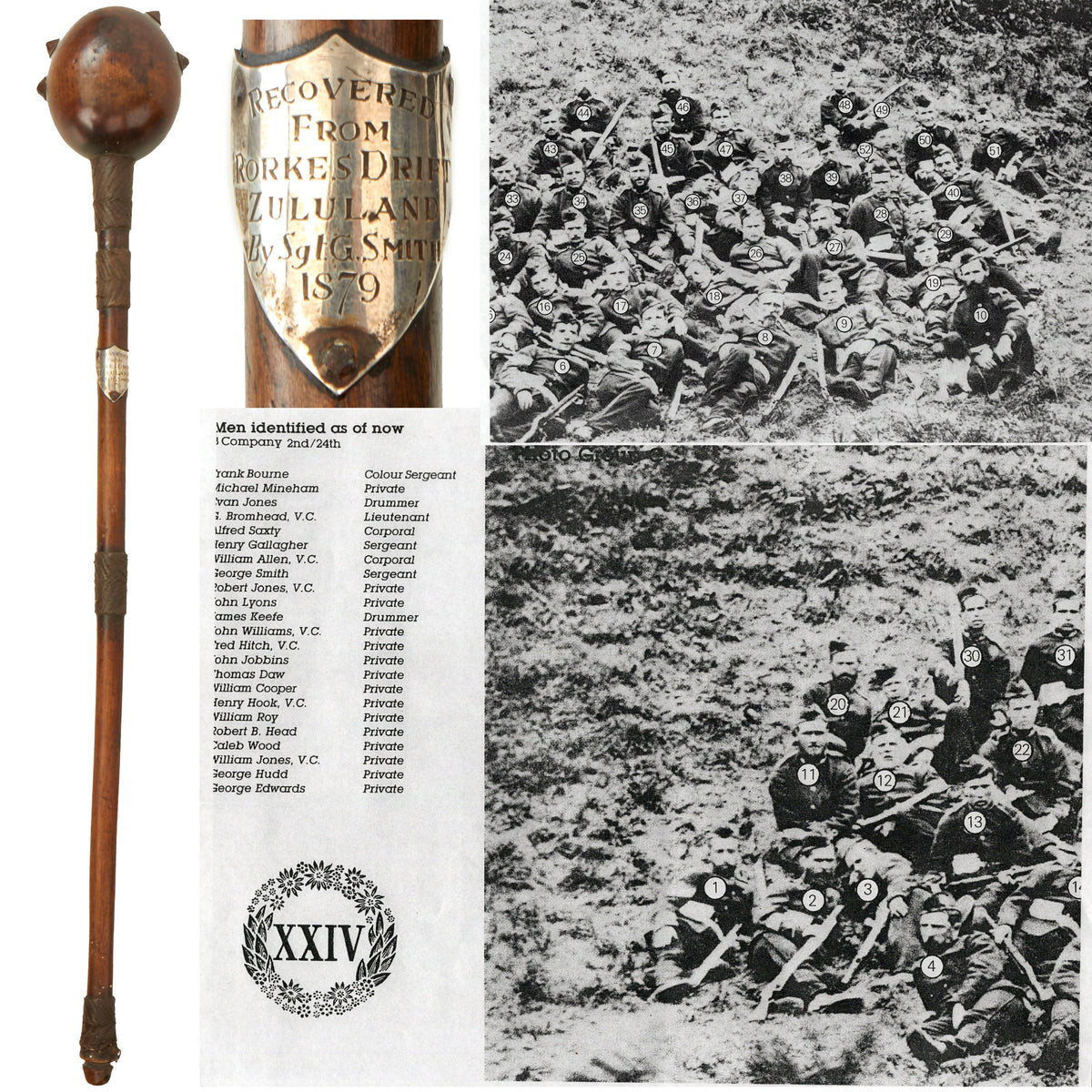

Original Item. One-of-a-Kind. The phrase Rorke’s Drift holds a deep resonance in the history of the British Empire. Eleven Victoria Crosses, Britain’s highest and most prestigious award for valor, were awarded for the battle, more than any other battle in history. This Knobkerrie war club bears an engraved silver plaque that states it was recovered from the site of the battle by Sergeant George Henry Smith, B Company, 2nd Battalion, 24th Regiment of Foot, who participated in the defense and survived.

The knobkerrie measures roughly 23” long, with an integrated head measured 3” in diameter. The head features four metal spikes and three shadows where spikes once were. The shaft of the knobkerrie is wrapped beautifully with wire in four distinct spots, two below the knob, one at the middle, and one at the opposite end. There is a small silver plaque below the second wiring, that reads:

RECOVERED

FROM

RORKES DRIFT

ZULULAND

BY SGT. G. SMITH

1879

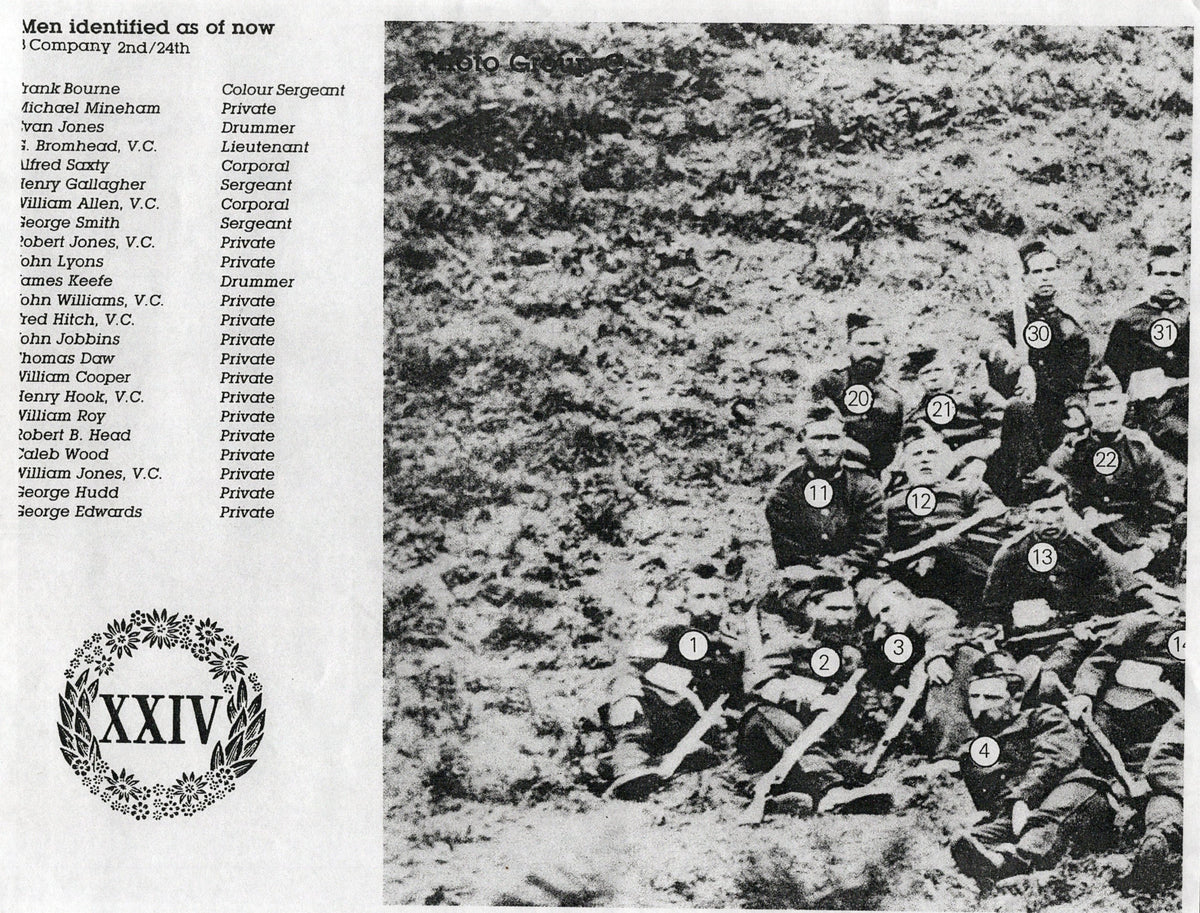

The top and bottom wire wrappings are a bit loose but show no risk of coming undone. We have conducted a great deal of research on Sergeant George Smith, as well as providing a photograph of him with B Company, 2/24th Regiment.

Please note: Other than the engraved plaque there is no further historical provenance to support the claim that this was recovered from the battle nor that it was owned by Sgt. Smith.

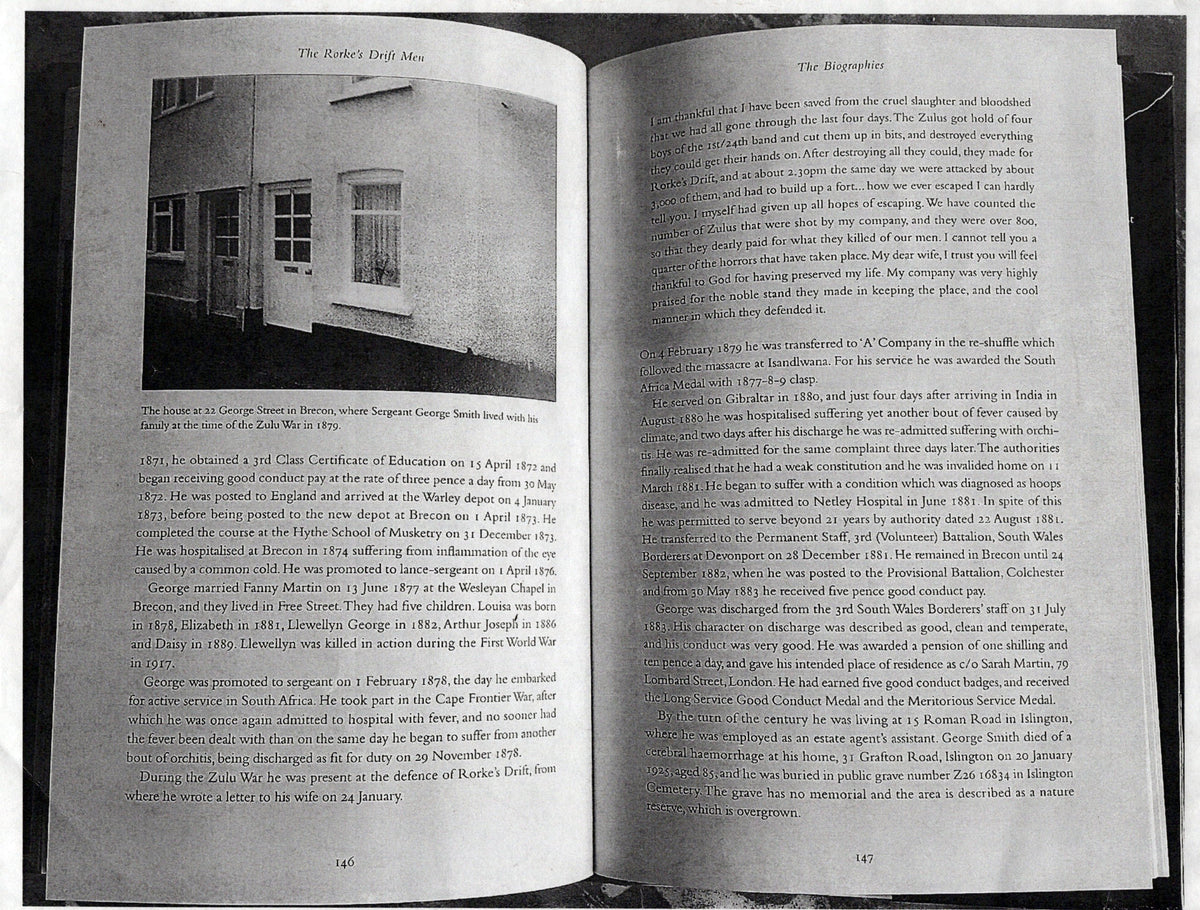

George Henry Smith was born on January 26th, 1840 at Bird Cage Fields, Stamford Hill, North London, the sixth child of seven born to George Smith, a dairyman’s laborer, and his wife Susannah. The family moved to Moore’s Field Cottages, Stamford Hill, and by 1851 they had moved to 6 South Row, Stamford Hill. Smith enlisted in the Royal London Militia on April 14th, 1860, before joining the regular army on May 29th, 1860 at Worship Street Police Court, Finsbury. As 1387 Private G. Smith, he was posted to the 2nd Battalion, 24th Regiment of Foot.

Smith arrived at Cork on May 31st, where he was awarded a penny a day good conduct pay. He was sent to Port Blair, India, where he was admitted to the hospital in December 1865, being treated for dysentery. He was twice admitted to the hospital in Rangoon suffering from boils and then fever, as well as inflammation of the testicle caused by an injury. He re-engaged on January 10th, 1868 to complete 21 years, and his good conduct pay increased to two pence a day from May 30th, 1868. He was posted to Madras on January 27th, 1869, and by March 5th he had moved to Secunderabad, where he was hospitalized with tonsillitis, followed by a couple bouts of enteric fever, attributed to a defective malaria injection. George was to have several more bouts of fever. He was promoted to Corporal on August 4th, 1871 and obtained a 3rd Class Certificate of Education on April 15th, 1872, and began receiving good conduct pay at the rate of three pence a day. He completed the course at the Hythe School of Musketry on December 31st, 1872. Smith would be promoted to Lance-Sergeant on April 1st, 1876.

Smith married Fanny Martin on June 13th, 1877 in Brecon, and they had five children, Louisa in 1878, Elizabeth in 1881, Llewellyn George in 1882, Arthur Joseph in 1886, and Daisy in 1889. Llewellyn George was killed in action during World War I in 1917.

Smith was promoted to Sergeant on February 1st, 1878, the day he embarked for active service in South Africa. He took part in the Cape Frontier War, after which he was once again admitted to the hospital with fever and then orchitis, being discharged for duty on November 29th, 1878. During the Anglo-Zulu War, he was present at the defense of Rorke’s Drift, from where he wrote a letter to his wife on January 24th, 1879:

I am thankful that I have been saved from the cruel slaughter and bloodshed that we had all gone through the last four days. The Zulus got hold of four boys of the 1st/24th band and cut them up in bits, and destroyed everything they could get their hands on. After destroying all they could, they made for Rorke’s Drift, and at about 2:30pm the same day we were attacked by about 3,000 of them, and had to build up a fort… how we ever escaped I can hardly tell you. I myself had given up all hopes of escaping. We have counted the number of Zulus that were shot by my company, and they were over 800, so they dearly paid for what they killed of our men. I cannot tell you a quarter of the horrors that have taken place. My dear wife, I trust you will feel thankful to God for having preserved my life. My company was very highly praised for the noble stand they made in keeping the place, and the cool manner in which they defended it.

On February 4th, 1879, he was transferred to ‘A’ Company in the reshuffle which followed the massacre at Isandlwana. For his service he was awarded the South Africa Medal with 1877-8-9 clasp. He served on Gibraltar in 1880 before suffering another bout of fever which alerted authorities to finally realize he had a weak constitution and “invalid” him home on March 11th, 1881. In spite of this he was able to serve beyond 21 years and was transferred to the permanent staff, 3rd Volunteer Battalion, South Wales Borderers at Devonport on December 28th, 1881, finally being discharged on July 31st, 1883. Smith was given a pension of one shilling and ten pence a day, having earned five good conduct badges, the Long Service Good Conduct Medal, and the Meritorious Service Medal. Smith retired in Islington, where he died of a cerebral hemorrhage on January 20th, 1925, at the age of 85.

This Knobkerrie is a phenomenal piece of British history, being associated with one of the most infamous battles in history, the Defense of Rorke’s Drift. Made from the hard wood of a root ball of a tree with the shaft carved from just one limb, this would have been a fierce weapon to wield indeed. We have conducted a great deal of research on Sergeant George Smith, who served in the British Army for 23 years despite his many bouts of sickness, injury, and disposition. It is ready for further research and display, and to become the centerpiece of any collection of military history. This is truly a museum-quality piece, the likes of which will not appear in the open market again for a long time. Don’t miss it.

A Knobkierie, also spelled knobkerrie, knopkierie or knobkerry, is a form of war club used mainly in Southern and Eastern Africa. Typically they have a large knob at one end and can be used for throwing at animals in hunting or for clubbing an enemy’s head. The knobkierie is carved from a branch thick enough for the knob, with the rest being whittled down to create the shaft.

The name derives from the Afrikaans word knop, meaning knot or ball and the Nama (one of the Khoekhoe languages) word kierie, meaning cane or walking stick. The name has been extended to similar weapons used by the natives of Australia, the Pacific islands and other places. Knobkerries were an indispensable weapon of war, particularly among southern Nguni tribes such as the Zulu (as the iwisa) and the Xhosa.

A Knobkerrie collected by John Chard V.C. (Commander of the Outpost & Garrison) sold at auction in the U.K. in 2020 for $6,449.85 WITHOUT buyer’s premium, $8,958.12 WITH premium. That example was of similar construction to this, but bore no spikes or plaque.

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Angolan Rebel 1970s era 60mm Inert Display Mortar from Angolan Civil War Original Items

Uncategorized

Band of Brothers ORIGINAL GERMAN WWII Le. F.H. 18 10.5cm ARTILLERY PIECE Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armored Burgonet Helmet & Polearm from Scottish Castle Leith Hall Circa 1700 Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Australian WWII Owen MK1 Machine Carbine SMG Custom Fabricated Replica with Sling Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized