Original German WWI Trench Art Lot – Letter Openers & Matchbox Holder Original Items

$ 250,00 $ 100,00

Original Items. Only One Lot Available. This is a great little lot of WWI trench art that will add some great flair to your WWI collection. Each piece is uniquely designed and were made as souvenirs for Allied soldiers during Occupation. The letter openers use U.S. & French Cartridges. Like all deactivated ordnance, this lot is Not Available for Export.

The lot includes:

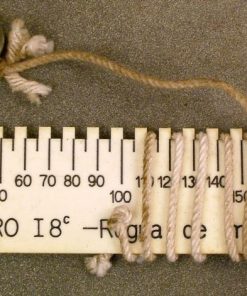

-Matchbox holder made from brass and German belt buckle emblem. Measures 2⅜ x 1⅝ x ¾”.

-Small ashtray with ornate engravings and German belt buckle emblem in middle. Measures 3” in diameter.

-Letter opener using U.S. 30-06 round as handle with small German crown. Letter opener has faint name of location engraved on. Measures 8¼”.

-Letter opener using French Lebel round as handle with small German crown. Belt buckle emblem attached to blade with ARGONNE engraved on blade. Measures 7¾” long.

This is a great lot of German, U.S., and French trench art, ready for further research and display!

Trench art is any decorative item made by soldiers, prisoners of war, or civilians[citation needed] where the manufacture is directly linked to armed conflict or its consequences. It offers an insight not only to their feelings and emotions about the war, but also their surroundings and the materials they had available to them.

Not limited to the World Wars, the history of trench art spans conflicts from the Napoleonic Wars to the present day. Although the practice flourished during World War I, the term ‘trench art’ is also used to describe souvenirs manufactured by service personnel during World War II. Some items manufactured by soldiers, prisoners of war or civilians during earlier conflicts have been retrospectively described as trench art.

There is much evidence to prove that some trench art was made in the trenches, by soldiers, during war. In With a Machine Gun to Cambrai, George Coppard tells of pressing his uniform buttons into the clay floor of his trench, then pouring molten lead from shrapnel into the impressions to cast replicas of the regimental crest. Chalk carvings were also popular, with contemporary postcards showing carvings in the rocky outcrops of dug-outs. Many smaller items such as rings and knives were made by soldiers either in front line or support trenches, especially in quieter parts of the line. Wounded soldiers were encouraged to work at crafts as part of their recuperation, with embroidery and simple forms of woodwork being common. Again from With a Machine Gun to Cambrai, George Coppard recalls that, while recuperating from wounds at a private house in Birkenhead, “one kind old lady brought a supply of coloured silks and canvas and instructed us in the art of embroidery. A sampler which I produced under her guidance so pleased her that she had it framed for me.”

An example of therapeutic embroidery during World War I is the work of British military in Egypt, who were photographed sewing and embroidering for Syrian refugees. There was also the Bradford Khaki Handicrafts Club, which was funded in Bradford, UK, in 1918, to provide occupational therapy and employment for men returning from the trenches in France.

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armored Burgonet Helmet & Polearm from Scottish Castle Leith Hall Circa 1700 Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Australian WWII Owen MK1 Machine Carbine SMG Custom Fabricated Replica with Sling Original Items

Uncategorized

Armoured Fighting Vehicles of the World: AFVs of World War One (Hardcover Book) New Made Items