Original German Pre-WWII Named 1936 Berlin Summer Olympic Decoration in Frame Original Items

$ 495,00 $ 148,50

Original Item: Only One Available. The German Olympic Decoration (German: Deutsche Olympia-Ehrenzeichen or Deutsches Olympiaehrenzeichen) was a civil decoration of Germany awarded to administrators of the IV Olympic Winter Games in Garmisch-Partenkirchen and the Games of the XI Olympiad in Berlin 1936. The award was not intended for actual participants in the Olympic Games, but rather in recognition of those who had orchestrated the “behind the scenes” preparations and work for the events.

The German Olympic Decoration was awarded in three classes, the highest of which was a “Neck Order”:

- 1st Class

- 2nd Class

- German Olympic Commemorative Medal

The German Olympic Commemorative Medal (German: Deutsche Olympia-Erinnerungsmedaille) was established to recognize service in connection with the preparation work and execution of the game events. The medal was not restricted to German nationals.

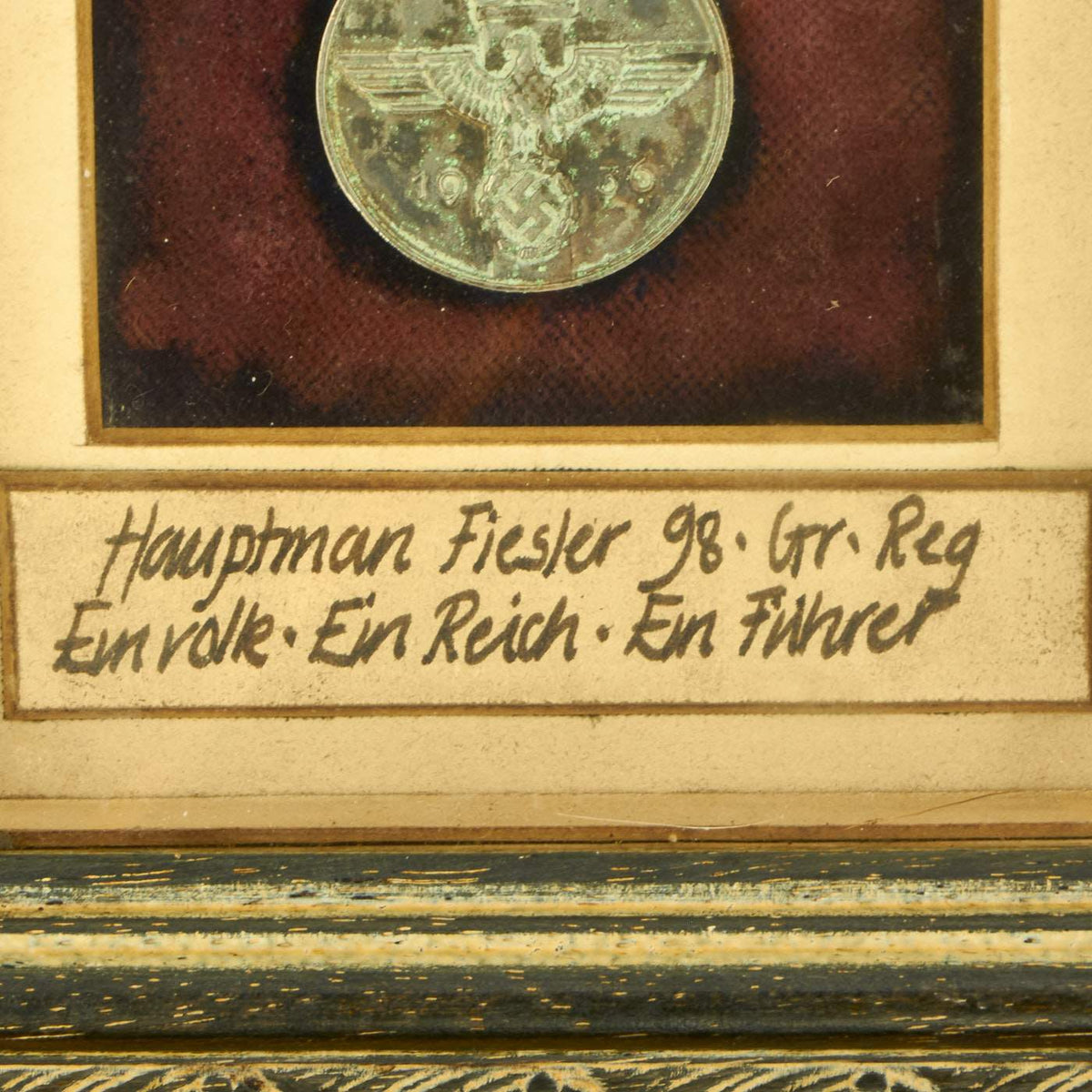

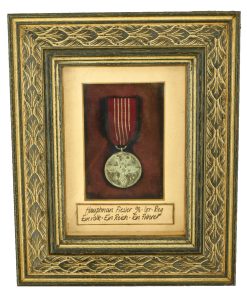

This is a very nice named and framed 1936 Berlin German Olympic Commemorative Medal. Constructed in silvered bronze, it measures 37mm diameter, and is in great condition, complete with the original ribbon. Just below the award is the name and rank of the recipient:

Hauptman Fiesler 98. Gr. Reg.

Ein volk. Ein Reich. Ein Führer

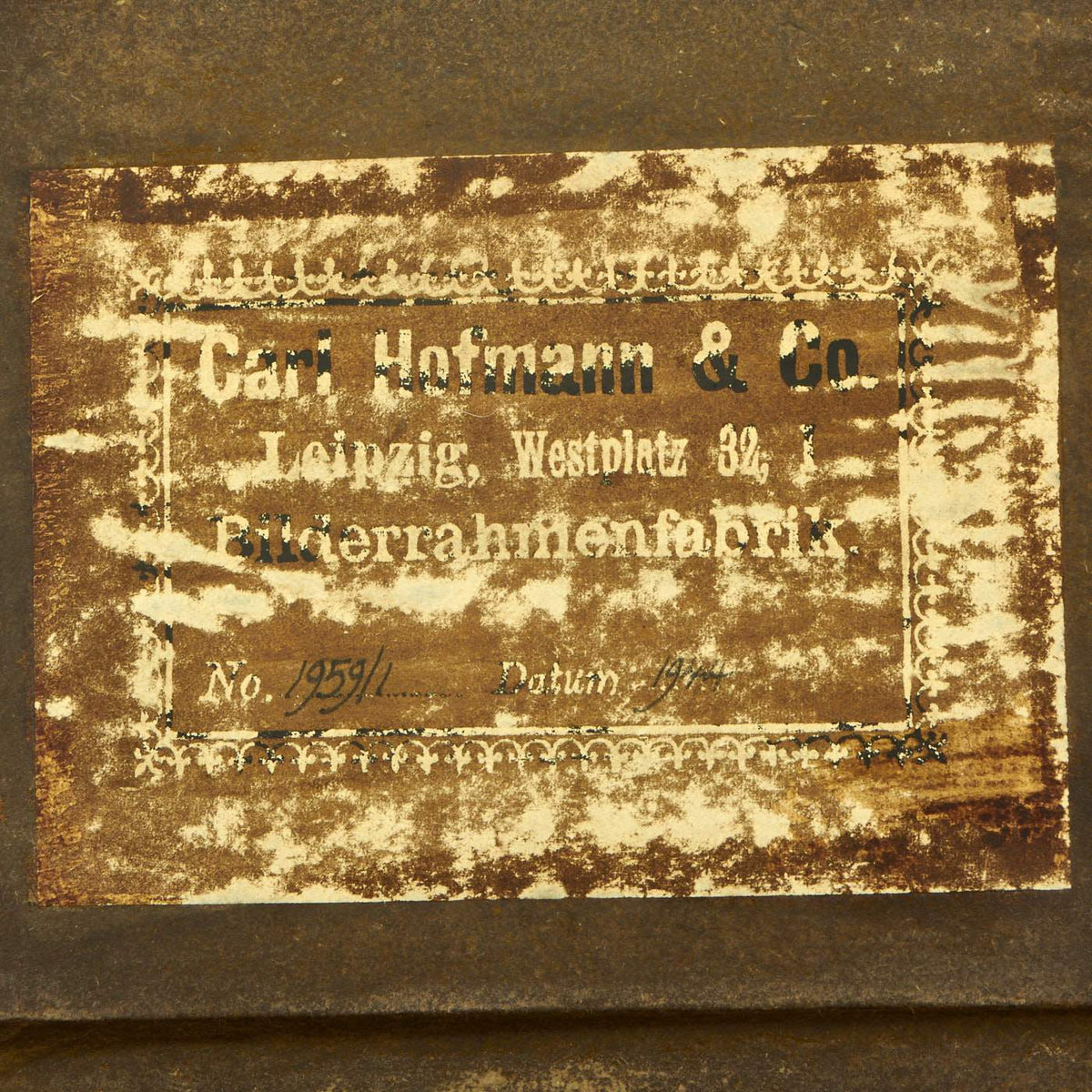

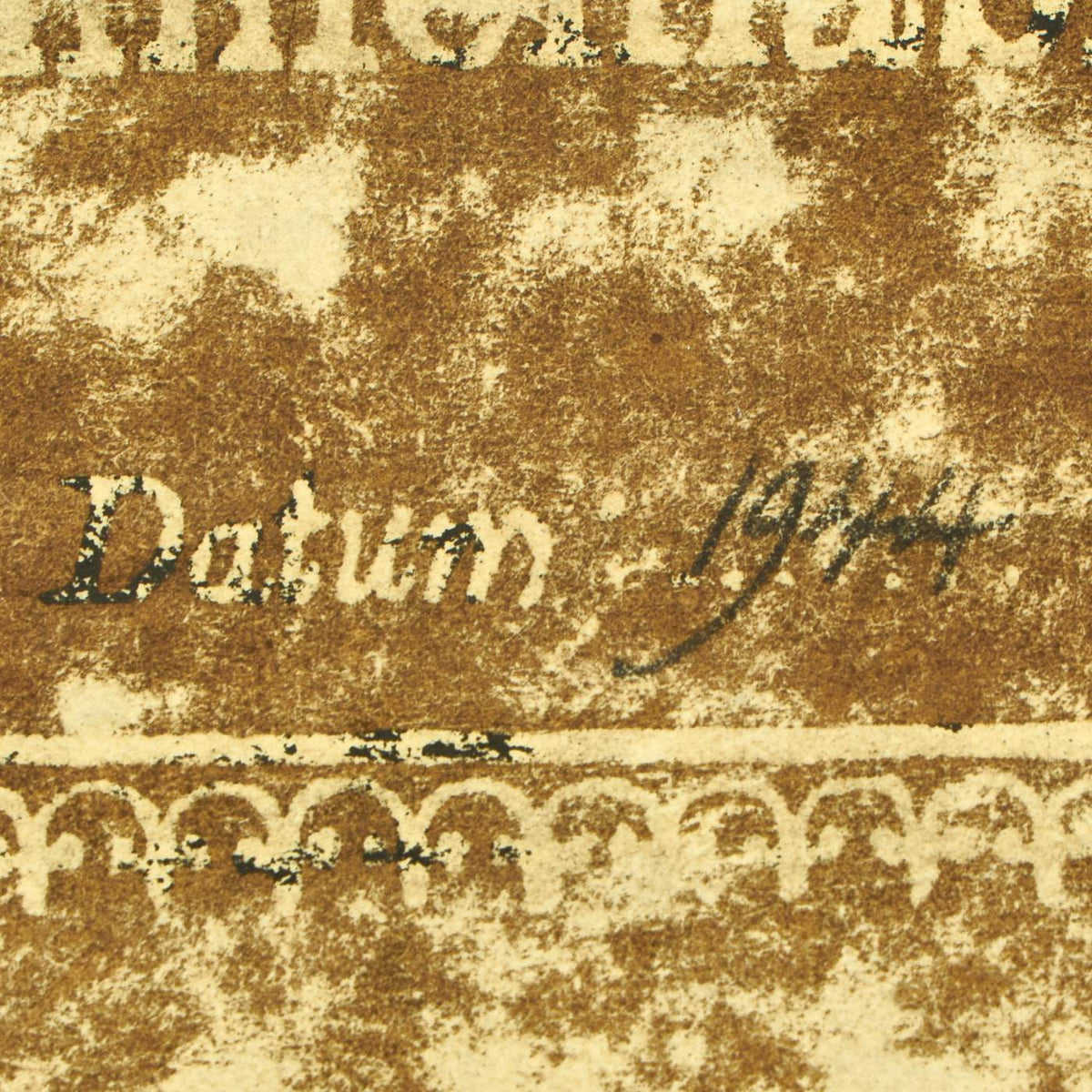

This would indicate that Capt. Fiesler was part of the 98th Regiment during the pre WWII period. The back of the frame still has the original label from the framer, which gives a date of 1944. The frame itself measures 11″H x 9″W x 1 1/4″, and is in very good condition.

Definitely some great research potential here!

The 1936 Olympic Games is a confusing study. The most hospitable and dramatic Games up to that point were hosted by one of the cruelest regimes in history. Awarded to Germany in 1931, the Games of the XI Olympiad became a propaganda spectacle for the NSDAP. With the full financial and organizing force of the NSDAP government behind the planning, the 1936 Games transformed the Olympics from an underfunded amateur competition into a spectacle that nations could look toward for both an economic and public relations boost.

German Olympic Committee officials Carl Diem and Theodor Lewald undertook the massive responsibility of planning Games that would outdo the 1932 Games in Los Angeles and meet the NSDAP standard for large, organized events. During the preparations, the NSDAP removed Lewald, who had Jewish ancestry, from his official post as Olympic Committee President and demoted him to advisor. Despite the change, the remaining members of the German Olympic Committee were determined to outdo all previous Olympic hosts in size, accommodations, and pageantry.

One of the most defining innovations of the 1936 Olympics was the Olympic Torch Relay. Never before in either the ancient or modern Olympics had a torch been lit in Athens and carried to the Games. With cooperation from Greece and every nation along the route, the first Olympic torch arrived in Berlin for the opening of the Games via a young male runner chosen by AH himself for embodying the Aryan ideal. The Games were also the first to be televised with closed circuit feeds present throughout the Olympic Village. Acclaimed filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl revolutionized sport documentaries with Olympia.

The Games are also famous for the accomplishments of American sprinter Jesse Owens. Owens, an African American, won four gold medals in the Track and Field events, prompting spectators around the world to declare that he disproved AH’s notions of Aryan superiority. Reporters at the time declared that AH had snubbed Owens by refusing to shake his hand. The previous day, AH had been warned about acknowledging athletes publicly. The president of the International Olympic Committee informed AH that he could not publicly congratulate only German winners. He must acknowledge all winners or none. AH, not wanting to cause a very visible international incident at the Games, decided to remain a spectator while in public view. Behind the scenes, however, he would congratulate all German medal winners.

Leading up to the Games, newspapers around the world had printed stories of the harsh treatment of Jews in Germany, and many attendees expected the worst. However, the picture of Germany seen by athletes and spectators was one of hospitality, order, and patriotism. In order to project the image a progressive, orderly nation, the NSDAP ordered the removal of all public anti-Semitic signs and publications. The open persecution of Jewish citizens was effectively put on hold in all areas that could be accessible to outsiders. Some reporters and Olympic officials hoped that this signaled a softer approach to racial issues in Germany, but it was short lived. Members of the International Olympic Committee were confident that hosting the Games had positively influenced Germany and would make them more cooperative in international affairs. After the Olympics ended, the NSDAP were even more emboldened and took further steps to marginalize and persecute Jews, political dissenters, and other “undesirables.” In fact, AH was planning to make the Olympics his own, permanently stage the Games in Nuremburg beginning in 1944.

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Angolan Rebel 1970s era 60mm Inert Display Mortar from Angolan Civil War Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Band of Brothers ORIGINAL GERMAN WWII Le. F.H. 18 10.5cm ARTILLERY PIECE Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized