Original French Nine Years’ War Era 17th Century Sergeant’s Partisan-Spontoon Polearm Head Original Items

$ 895,00 $ 223,75

Original Item: Only One Available. A partisan is a type of polearm that was used in Europe during the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. It consisted of a spearhead mounted on a long wooden shaft, with protrusions on the sides which aided in parrying sword thrusts. The partisan was often used by infantry soldiers, who would use the weapon to fend off cavalry charges. The protrusions on the sides of the spearhead were also useful for catching and trapping an opponent’s sword, allowing the user to disarm them. In profile, the head of a partisan may look similar to other types of polearm, such as the halberd, pike, ranseur, spontoon, ox tongue, or spetum.

The arrival of practical firearms led to the obsolescence of the partisan and other polearms. Despite this, the weapon continued to be used for many years as a ceremonial weapon. Ceremonial partisans can still be seen in the hands of guards at important buildings or events.

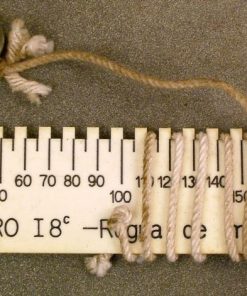

This polearm head is a hybrid of the Partisan and Spontoon and is simply referred to as “Partisa-Spontoon” to keep it simple. The design and distinct shape aided in identifying it as a French example and dating to the Mid to Late 17th Century, around the time France was involved in multiple ongoing conflicts. The condition is excellent with the etched designs still clear and stunning in appearance. It measures approximately 11 inches in length with the widest point measuring 4 inches.

A wonderful example ready for display.

Nine Years War

The Nine Years’ War (1688–1697), often called the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg, was a conflict between France and a European coalition which mainly included the Holy Roman Empire (led by the Habsburg monarchy), the Dutch Republic, England, Spain, Savoy, Sweden and Portugal. Although not the first European war to spill over to Europe’s overseas colonies, the events of the war spread to such far away places as the Americas, India, and West Africa. It is for this reason that it is sometimes considered the first world war. The conflict encompassed the Glorious Revolution in England, where William of Orange deposed the unpopular James VII and II and subsequently struggled against him for control of Scotland and Ireland, and a campaign in colonial North America between French and English settlers and their respective Native American allies.

Louis XIV of France had emerged from the Franco-Dutch War in 1678 as the most powerful monarch in Europe, an absolute ruler whose armies had won numerous military victories. Using a combination of aggression, annexation, and quasi-legal means, Louis XIV set about extending his gains to stabilize and strengthen France’s frontiers, culminating in the brief War of the Reunions (1683–1684). The Truce of Ratisbon guaranteed France’s new borders for twenty years, but Louis XIV’s subsequent actions—notably his Edict of Fontainebleau (the revocation of the Edict of Nantes) in 1685—led to the deterioration of his political preeminence and raised concerns among European Protestant states.

Louis XIV’s decision to cross the Rhine in September 1688 was designed to extend his influence and pressure the Holy Roman Empire into accepting his territorial and dynastic claims. However, Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor and German princes resolved to resist. The States General of the Netherlands and William III brought the Dutch and English into the conflict against France and were soon joined by other states, which now meant the French king faced a powerful coalition aimed at curtailing his ambitions.

The main fighting took place around France’s borders in the Spanish Netherlands, the Rhineland, the Duchy of Savoy, and Catalonia. The fighting generally favored Louis XIV’s armies, but by 1696 his country was in the grip of an economic crisis. The Maritime Powers (England and the Dutch Republic) were also financially exhausted, and when Savoy defected from the Alliance, all parties were keen to negotiate a settlement. By the terms of the Peace of Ryswick, Louis XIV retained the whole of Alsace but in exchange had to return Lorraine to its ruler and give up any gains on the right bank of the Rhine. Louis XIV also recognized William III as the rightful king of England, while the Dutch acquired a barrier fortress system in the Spanish Netherlands to help secure their borders.

The peace would be short-lived. With the ailing and childless Charles II of Spain’s death approaching, a new dispute over the inheritance of the Spanish Empire was soon to embroil Louis XIV and the Grand Alliance in the War of the Spanish Succession.

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Band of Brothers ORIGINAL GERMAN WWII Le. F.H. 18 10.5cm ARTILLERY PIECE Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armoured Fighting Vehicles of the World: AFVs of World War One (Hardcover Book) New Made Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armored Burgonet Helmet & Polearm from Scottish Castle Leith Hall Circa 1700 Original Items

Uncategorized