Original Civil War Union Officer’s Slouch Hat with 11th Corps Badge and Officer’s Hat Cord Original Items

$ 1.895,00 $ 473,75

Original Item: One-Of-A-Kind. This is a stunning example of a Civil War Union Officer’s Hat worn by a member of the 11th Corps during the war. The Hat is a typical 1860’s produced hat, made of black fur felt with a 2 ½” wide brim. The hat no longer retains its sweatband. The original silk hat band is somewhat intact and the brim edging is missing.

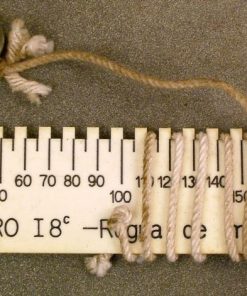

The hat features an original Civil War officer’s bullion hat cord, which appears to have been placed on the hat for a very, very, long time. The hat shows signs of wear from honest campaign use during the war. Hand-sewn on the front of the hat is a beautiful example of a 11th Corps Badge, which is made from red wool and gold bullion thread. The XI Corps (Eleventh Army Corps) was a corps of the U.S. Army during the American Civil War, best remembered for its involvement in the battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg in 1863. The corps was composed primarily of German-American regiments.

The overall condition is quite nice and there are a few areas of material loss and tearing. Finding honest examples such as this one is rare these days and you do not want to pass up on the chance for this one.

Comes ready for further research and display.

The XI Corps was an amalgamation of two separate commands. These were John Fremont’s Army of the Mountain Department and Louis Blenker’s division of German immigrants. Blenker had led a German brigade at First Bull Run, although it was held in reserve and saw no major fighting, and afterward became a division commander in the new Army of the Potomac. Intended to go to the Virginia Peninsula in the spring of 1862, Blenker’s troops were instead detached and sent out west to join Fremont. The division got lost and ran out of supplies, resulting in soldiers dropping out of the ranks from hunger, fatigue, and sickness. Many German soldiers angered locals in the Shenandoah Valley by indiscriminately looting homes and farms. They also did not have a good relationship with the native-born soldiers in Fremont’s command—eventually, Brig. Gen William Rosecrans found the lost division and brought them to Fremont’s headquarters at Petersburg, West Virginia.

At the Battle of McDowell on May 5, Robert Schneck’s division unsuccessfully attacked Stonewall Jackson’s army. On June 8, Fremont’s entire command engaged Jackson again at the Battle of Cross Keys, where Blenker’s German troops were routed from the field in their first battle. By the end of the month, Brig. Gen Carl Schurz wrote to President Lincoln that the German regiments suffered from hunger, lack of tents and shoes, and could barely fight. Of the 10,000 men Blenker had had with him in March, less than 7000 were still present for duty in late June.

On June 26, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln ordered that “the troops of the Mountain Department, heretofore under the command of General John C. Frémont, shall constitute the First Army Corps, under the command of General Frémont.” The corps thus formed was, for the most part, the same as the one afterward known as the XI Corps, and within a short time, it was officially designated as such. This order of President Lincoln was included in the one constituting John Pope’s Army of Virginia, which was formed from the three commands of Frémont, Nathaniel P. Banks, and Irvin McDowell.

Fremont was offended at serving under Pope, whom he outranked, and resigned his command. Major General Franz Sigel thus assumed command of the corps on June 29. Many of the German soldiers could speak little English beyond “I fights mit Sigel” (“I’ll fight with Sigel”), which was their proud slogan. President Lincoln chose Sigel less for his military skills than his influence on this crucial political constituency. In early August, Louis Blenker stepped down from command due to the lingering effects of an injury sustained during the spring; he died in October 1863. Sigel was in command at the Second Battle of Bull Run, where the corps was in the thick of the fighting, losing 295 killed, 1,361 wounded, and 431 missing; total, 2,087. At this time, the three divisions were commanded by Generals Robert C. Schenck, Adolph von Steinwehr, and Carl Schurz; there was also an independent brigade attached, under the command of Brig. Gen. Robert H. Milroy. During the first day of the battle, the corps performed a series of unsuccessful assaults on Stonewall Jackson’s center and left flank. On the second day, it was in the middle of the desperate fighting against James Longstreet’s Confederates on Chinn Ridge, where Sigel and Schneck were wounded and Col. John Koltes, one of the brigade commanders, was killed.

By General Orders No. 129, September 12, 1862, the corps’s designation was changed to that of the XI Army Corps, a necessary change, as McDowell’s command had resumed its original title of the I Corps. The corps had suffered severely at Second Bull Run and came close to being routed from the field, so it was left behind in Washington D.C. during the Maryland Campaign to rest and refit. Robert Milroy’s brigade was detached and sent off to West Virginia. Col. Nathaniel McLean was promoted to brigadier general and succeeded Robert Schneck as commander of the 1st Division. During the fall months, the XI Corps occupied various outposts along the Potomac River and Northern Virginia. In December, it marched to Fredericksburg but was not present at the battle, after which it went into winter quarters at Stafford, Virginia.

Battle of Chancellorsville

With the ascension of Joseph Hooker to command of the army in February 1863, Franz Sigel was the second most senior officer in the ranks. Because of this and because the XI Corps was the smallest in the Army of the Potomac, he felt that it deserved to be enlarged. His request denied, Sigel angrily resigned his command. Replacing him was Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard, who had lately been complaining that he deserved a corps command since General Daniel Sickles, his junior in rank, had gotten one. Howard quickly established a poor relationship with the troops due to his intense religious fervor, which especially alienated the anti-clerical Germans, and for bringing in two new, unpopular generals, Francis Barlow and Charles Devens. Devens, formerly a brigade commander in the IV and VI Corps, was given command of the 1st Division over Nathaniel McLean, who got demoted back to brigade command. The relationship between the two generals was touchy. Barlow, formerly of the II Corps, had a habit of being an aggressive martinet.

General Howard commanded the corps at Chancellorsville, May 1–3, 1863, at which time it numbered 12,169 effectives, and was composed of the divisions of Generals Charles Devens, von Steinwehr, and Schurz. It contained 27 regiments of infantry, of which 13 were German regiments. The men of the XI Corps were good soldiers, for the most part, tried and veteran troops, but their leadership let them down. On May 1, Robert E. Lee and his subordinate, “Stonewall” Jackson, came up with a risky, but daring, plan of attack. They would split their 40,000-man force at Chancellorsville, with Jackson taking his Second Corps of 28,000 men around to attack the U.S. right flank. On May 2, Jackson flawlessly executed his stealthy flanking march, whose target was the unlucky XI Corps. The right flank of the U.S. line was in the air; it was not anchored to any geographic barrier, such as a river or mountain. Although General Howard had been warned of Confederate movement across his front, he took no steps to prepare his command against Jackson’s attack; only two inoperative artillery pieces were pointed at the Wilderness.

When Jackson’s corps struck at about 6 p.m., the XI Corps was utterly unprepared, with many men eating supper. The attack was a complete success and the high point of Jackson’s military career, but it was an utter disaster for the XI Corps. Some of the brigades changed front to meet the attack, barely resisting, and were pushed back, hardly slowing the enemy down, but most of the corps fled to the east, running down the Orange Turnpike past the crossroads at Chancellorsville. The loss to the corps at Chancellorsville was 217 killed, 1,218 wounded, and 972 captured or missing, 2,407 in total.

Battle of Gettysburg

At Gettysburg, the corps was still under the command of Howard; the divisions were under Generals Francis C. Barlow, Steinwehr, and Schurz, and contained 26 regiments of infantry and 5 batteries of artillery. The corps’ men went into this battle with high anticipation and hoped to restore the reputation sullied at Chancellorsville. They arrived from south of town mid-day on July 1, 1863, aware that the I Corps was already heavily engaged just to the west of town. General Howard deployed one division (von Steinwehr’s) on the heights of Cemetery Hill as a reserve and the other two divisions north of town. Howard briefly commanded the entire battle until the arrival of Winfield S. Hancock.

The Confederate Second Corps under Richard S. Ewell arrived from the north with a devastating assault. Barlow’s division was deployed on the right, and he foolishly moved his force to a small hill (now known as Barlow’s Knoll), causing a salient in the line that could be attacked from multiple directions. The division of Jubal A. Early took advantage of this, and Barlow’s division reeled back. Barlow himself was wounded and captured. The collapse of the corps’ right flank had a domino effect on its left and the I Corps division to its left, resulting in a general retreat of U.S. forces through the town of Gettysburg to the safety of Cemetery Hill, losing many captured on the way. On the second day, the XI Corps participated in the gallant and successful defense of East Cemetery Hill against a second attack by Early. On the day before the battle of Gettysburg, the corps reported 10,576 officers and men for duty; its loss in that battle was 368 killed, 1,922 wounded, and 1,511 captured or missing; total, 3,801, out of less than 9,000 engaged.

Tennessee

After Gettysburg, George Meade decided to break up the XI Corps. Returning to Virginia after Gettysburg, on August 7, the 1st Division (Alexander Schimmelfennig’s and later George Henry Gordon’s) was permanently detached, having been ordered to Charleston Harbor. On September 24, the 2nd and 3rd divisions (Steinwehr’s and Schurz’s) were ordered to Tennessee, together with the XII Corps under the command of Former Army of the Potomac commander Joseph Hooker. These two corps, numbering over 20,000 men, were transported, within a week, over 1,200 miles, and placed on the banks of the Tennessee River, at Bridgeport, without an accident or detention.

During the following month, on October 29, Howard’s two divisions were ordered to support the XII Corps at the Battle of Wauhatchie, opening the supply lines to the besieged city of Chattanooga. Arriving there, Col. Orland Smith’s Brigade of von Steinwehr’s Division charged up a steep hill in the face of the enemy, receiving but not returning the fire, and drove James Longstreet’s veterans out of their entrenchments, using the bayonet alone. Some of the regiments in this affair suffered a severe loss. Still, their extraordinary gallantry won extravagant expressions of praise from various generals high in rank, including General Ulysses S. Grant. A part of the XI Corps was also actively engaged at Missionary Ridge, where it cooperated with William T. Sherman’s forces on the left. After this battle, it was ordered to East Tennessee for the relief of Knoxville, a campaign whose hardships and privations exceeded anything within the previous experience of the command.

In April 1864, the two divisions of the XI Corps were broken up and transferred to the newly formed XX Corps, which was put under Hooker’s Command. General Howard was assigned to the command of the IV Corps and was promoted to the command of the Army of the Tennessee when James B. McPherson was killed at the Battle of Atlanta. Hooker was enraged by Howard’s promotion (because he thought he deserved it himself and never forgave Howard for what happened at Chancellorsville) and resigned in protest. Hooker was replaced by Henry Slocum.

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Australian WWII Owen MK1 Machine Carbine SMG Custom Fabricated Replica with Sling Original Items

Uncategorized

Angolan Rebel 1970s era 60mm Inert Display Mortar from Angolan Civil War Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Band of Brothers ORIGINAL GERMAN WWII Le. F.H. 18 10.5cm ARTILLERY PIECE Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armoured Fighting Vehicles of the World: AFVs of World War One (Hardcover Book) New Made Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized