Original Chinese Qing Dynasty Panthay Rebellion Era Jian Short Sword With Tortoiseshell Wood Scabbard – “The Gentleman of Weapons” Original Items

$ 395,00 $ 118,50

Original Item: Only One Available. The jian is a double-edged straight sword used during the last 2,500 years in China. The first Chinese sources that mention the jian dates to the 7th century BCE, during the Spring and Autumn period; one of the earliest specimens being the Sword of Goujian. Historical one-handed versions have blades varying from 45 to 80 centimeters (18 to 31 inches) in length. The weight of an average sword of 70-centimeter (28-inch) blade-length would be in a range of approximately 700 to 900 grams (1.5 to 2 pounds). There are also larger two-handed versions used for training by many styles of Chinese martial arts.

Professional jian practitioners are referred to as jianke.

In Chinese folklore, it is known as “The Gentleman of Weapons” and is considered one of the four major weapons, along with the gun (staff), qiang (spear), and the dao (saber). These swords are also sometimes referred to as taijijian or “tai chi swords”, reflecting their current use as training weapons for taijiquan practitioners, though there were no historical jian types created specifically for taijiquan.

A guard or hilt protects the hand from an opposing blade. Guard shapes varied, but often had short wings or lobes pointing either forward or backward, the latter sometimes having an “ace of spades” appearance. This one appears as short wings pointing towards the pommel. Early jian often had very small, simple guards. From the Song and Ming periods onward guards could feature zoomorphic shapes, or have crossbars and quillons. A minority of jian featured the disc-shaped guards associated with dao. The guard is unfortunately loose and has a lot of movement present.

The jian’s hilt can accommodate the grip of both hands or one hand plus two or three fingers of the other hand. Two-handed jiàn of up to 1.6 meters (63 inches) in length, known as shuangshou jian, existed but were not as common as the one-handed version. The longer two-handed handle could be used as a lever to lock the opponent’s arm if necessary. Grips are usually of fluted wood or covered in rayskin, with a minority being wrapped with cord. This is a single handed example with fluted wood grip, which is unfortunately cracked on one side the length of the handle.

The end of the handle was finished with a pommel for balance, to prevent the handle from sliding through the hand if the hand’s grip should be loosened, and for striking or trapping the opponent as opportunity required—such as in “withdrawing” techniques. The pommel was historically peened onto the tang of the blade; thereby holding together as one solid unit the blade, guard, handle, and pommel. Most jian of the last century or so are assembled with a threaded tang onto which the pommel or pommel-nut is screwed. This example does not appear to be a threaded tang, however we do not see any signs of it being peened over, just an open hole which shows what appears to be wood.

Sometimes a tassel is attached to the hilt. During the Ming Dynasty these were usually passed through an openwork pommel, and in the Qing through a hole in the grip itself; modern swords usually attach the tassel to the end of the pommel. The hole is present in the grip, as standard with Qing era swords. Historically these were likely used as lanyards, allowing the wielder to retain the sword in combat. There are some sword forms which utilize the tassel as an integral part of their swordsmanship style (sometimes offensively), while other schools dispense with sword tassels entirely. The movement of the tassel may have served to distract opponents, and some schools further claim that metal wires or thin silk cords were once worked into the tassels for impairing vision and causing bleeding when swept across the face. The tassel’s use now is primarily decorative. There is no tassel present in this example.

The blade itself is customarily divided into three sections for leverage in different offensive and defensive techniques. The tip of the blade is the jiànfeng, meant for stabbing, slashing, and quick percussive cuts. The jiànfeng typically curves smoothly to a point, though in the Ming period sharply angled points were common. Some antiques have rounded points, though these are likely the result of wear. The middle section is the zhongren or middle edge, and is used for a variety of offensive and defensive actions: cleaving cuts, draw cuts, and deflections. The section of blade closest to the guard is called the jiàngen or root, and is mainly used for defensive actions; on some late period jian, the base of the blade was made into a ricasso. These sections are not necessarily of the same length, with the jiànfeng being only three or four inches long.

Jian blades generally feature subtle profile taper (decreasing width), but often have considerable distal taper (decreasing thickness), with blade thickness near the tip being only half the thickness of the root’s base. Jiàn may also feature differential sharpening, where the blade is made progressively sharper towards the tip, usually corresponding to the three sections of the blade. The cross-section of the blade is typically lenticular (eye-shaped) or a flattened diamond, with a visible central ridge; ancient bronze jian sometimes have a hexagonal cross-section.

This is such a wonderful example of a Mid Qing Dynasty Jian. The scabbard has fared quite nicely, however, the lower drag and throat pieces are completely missing, but is in overall great condition for its age.

Comes more than ready for display!

Specifications

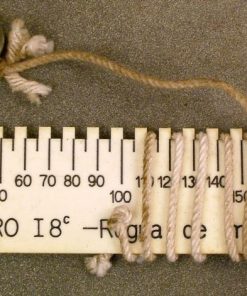

Blade Length: 16”

Hilt Length: 5 ½”

Scabbard Length: 17”

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Band of Brothers ORIGINAL GERMAN WWII Le. F.H. 18 10.5cm ARTILLERY PIECE Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Angolan Rebel 1970s era 60mm Inert Display Mortar from Angolan Civil War Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized