Original Canadian WWII U.S. Aluminum Megaphone Belonging to Lt. Gen. James Gavin – 82nd Airborne Division Commander Original Items

$ 895,00 $ 223,75

Original Item: One-Of-A-Kind. This is an incredible piece of WWII Airborne history! While a megaphone usually isn’t a “one-of-a-kind” item, this one is. Just below the lip on the speaking portion is a metal tag reading “Donated By James M. Gavin”.

James Maurice Gavin, sometimes called “Jumpin’ Jim” and “the jumping general”, was a senior United States Army officer, with the rank of lieutenant general, who was the third Commanding General (CG) of the 82nd Airborne Division during World War II. During the war, he was often referred to as “The Jumping General” because of his practice of taking part in combat jumps with the paratroopers under his command; he was the only American general officer to make four combat jumps in the war.

Gavin was the youngest major general to command an American division in World War II, being only 37 upon promotion, and the youngest lieutenant general after the war, in March 1955. He was awarded two Distinguished Service Crosses and several other decorations for his service in the war. During combat, he was known for his habit of carrying an M1 rifle, typically carried by enlisted U.S. infantry soldiers, instead of the M1 carbine, which officers customarily carried.

Gavin also worked against segregation in the U.S. Army, which gained him some notability. After the war, Gavin served as United States Ambassador to France from 1961 to 1962.

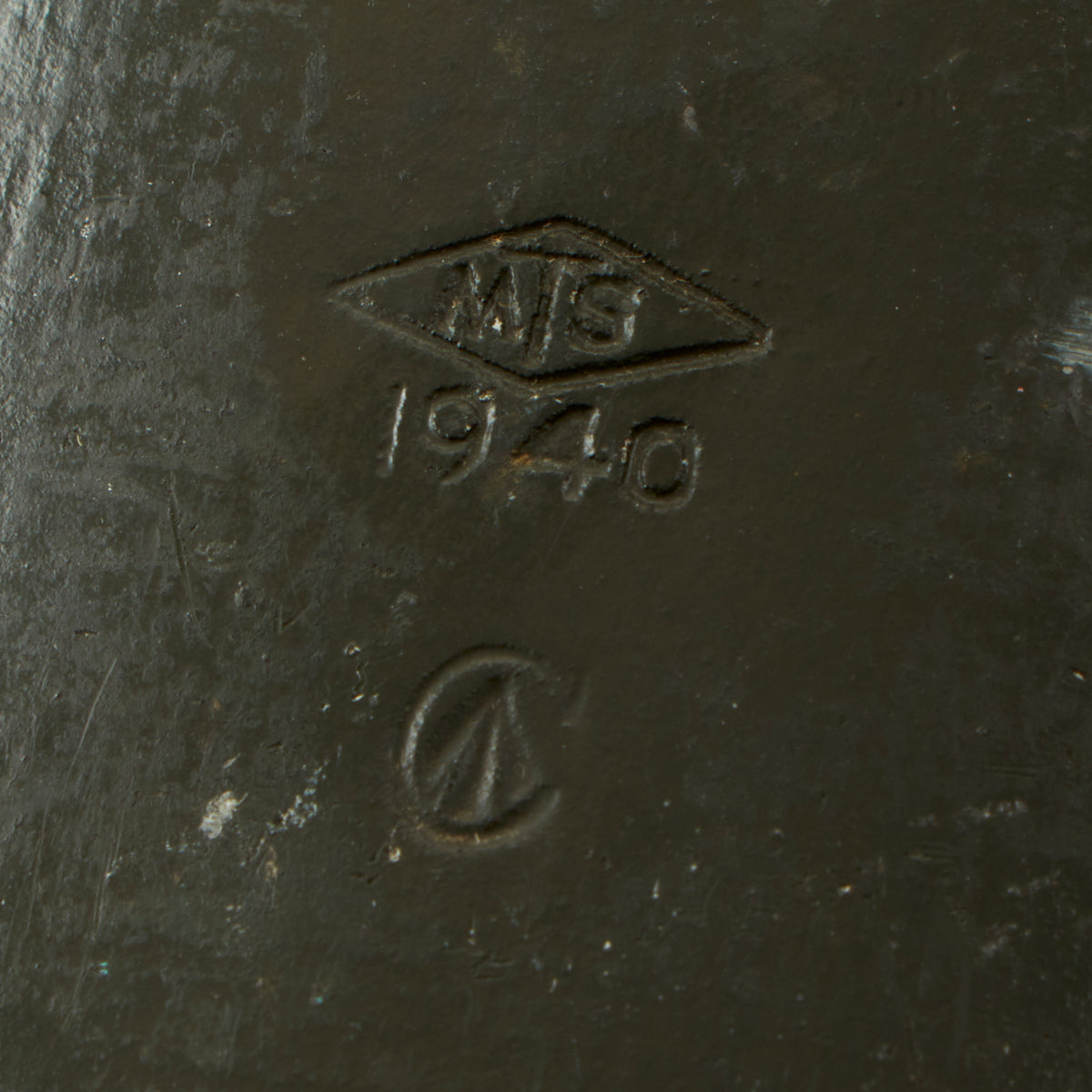

The megaphone is a Canadian broad arrow stamped with the date 1940 and was

manufactured by MTS. The megaphone is in solid working condition with no significant damage other than minor paint loss and chipping.

This is a beautiful and genuine example of a Canadian Army megaphone used by a famous American Airborne General during WWII. Comes ready to display!

General James Maurice Gavin: The “Jumping General”

Gavin was born in Brooklyn, New York, on March 22, 1907. His precise ancestry is unclear. His mother may have been an Irish immigrant, Katherine Ryan, and his father James Nally (also of Irish heritage), although official documentation lists Thomas Ryan as his father; possibly in order to make the birth legitimate. The birth certificate lists his name as James Nally Ryan, although Nally was crossed out. When he was about two years old, he was placed in the Convent of Mercy orphanage in Brooklyn, where he remained until he was adopted in 1909 by Martin and Mary Gavin from Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania, and given the name James Maurice Gavin.

Gavin took his first job as a newspaper delivery boy at the age of 10. By the age of 11, he had two routes and was an agent for three out-of-town papers. During this time, he enjoyed following articles about World War I. In the eighth grade, he moved on from the paper job and started working at a barbershop. There he listened to the stories of the old miners. This led him to realize he did not want to be a miner. In school, he learned about the Civil War. From that point on, he decided to study everything he could about the subject. He was amazed at what he discovered and decided if he wanted to learn this “magic” of controlling thousands of troops, from miles away, he would have to continue his education at the United States Military Academy at West Point.

His adoptive father was a hard-working coal miner, but the family still had trouble making ends meet. Gavin quit school after eighth grade and became a full-time clerk at a shoe store for $12.50 a week. His next stint was as a manager for Jewel Oil Company. A combination of restlessness and limited future opportunities in his hometown caused Gavin to run away from home. In March 1924, on his 17th birthday, he took the night train to New York. The first thing he did upon arriving was to send a telegram to his parents saying everything was all right to prevent them from reporting him missing to the police. After that, he started looking for a job.

At the end of March 1924, aged 17, Gavin spoke to a U.S. Army recruiting non commissioned officer. Since he was under 18, he needed parental consent to enlist. Knowing that his adoptive parents would not consent, Gavin told the recruiter he was an orphan. The recruiter took him and a couple of other underage boys, who were orphans, to a lawyer who declared himself their guardian and signed the parental consent paperwork. On April 1, 1924, Gavin was sworn into the U.S. Army, and was stationed in Panama. His basic training was performed on the job in his unit, the U.S. Coast Artillery at Fort Sherman. He served as a crewmember of a 155 mm gun, under the command of Sergeant McCarthy, who described him as fine. Another person he looked up to was his first sergeant, an American Indian named “Chief” Williams.

Gavin spent his spare time reading books from the library, notably Great Captains and a biography of Hannibal. He had been forced to quit school in seventh grade in order to help support his family, and acutely felt his lack of education. In addition, he made excursions in the region, trying to satisfy his boundless curiosity about everything. First Sergeant Williams recognized Gavin’s potential and made him his assistant; Gavin was promoted to corporal six months later.

He wished to advance in the army, and on Williams’s advice, applied to a local army school, from which the best graduates got the chance to attend the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York. Gavin passed the physical examinations and was assigned with a dozen other men to a school in Corozal, which was a small army depot in the Canal Zone. He started school on September 1, 1924. In order to prepare for the entrance exams into West Point, Gavin was tutored by another mentor, Lieutenant Percy Black, from 8 o’clock in the morning until noon on algebra, geometry, English, and history. He passed the exams and was allowed to apply to West Point.

Gavin arrived at West Point in the summer of 1925. On the application forms, he indicated his age as 21 (instead of 18) to hide the fact that he was not old enough to join the army when he did. Since Gavin missed the basic education which was needed to understand the lessons, he rose at 4:30 every morning and read his books in the bathroom, the only place with enough light to read. After four years of hard work, he graduated in June 1929. In the 1929 edition of the West Point yearbook, Howitzer, he was mentioned as a boxer and as the cadet who had already been a soldier. After his graduation and his commissioning as a second lieutenant, he married Irma Baulsir on September 5, 1929.

Gavin was posted to Camp Harry J. Jones near Douglas, Arizona, on the U.S.-Mexican border. This camp housed the 25th Infantry Regiment (one of the entirely African-American Buffalo Soldier regiments). He stayed in this posting for three years.

Afterwards, Gavin attended the United States Army Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia. This school was managed by Colonel George C. Marshall, who had brought Joseph Stilwell with him to lead the Tactics department. Marshall and Stillwell taught their students not to rely on lengthy written orders, but rather to give rough guidelines for the commanders in the field to execute as they saw fit, and to let the field commanders do the actual tactical thinking; this was contrary to all other education in the US Army thus far. Gavin himself had this to say about Stilwell and his methods: “He was a superb officer in that position, hard and tough worker, and he demanded much, always insisting that anything you ask the troops to do, you must be able to do yourself.”

The time spent at Fort Benning was a happy time for Gavin, but his marriage with Irma Baulsir was not going well. She had moved with him to Fort Benning, and lived in a town nearby. On December 23, 1932 they drove to Baulsir’s parents in Washington, D.C., to celebrate Christmas together. Irma decided she was happier there, and remained with her parents. In February 1933, Irma became pregnant. Their daughter, Gavin’s first child, Barbara, was born while Gavin was away from Fort Sill on a hunting trip. “She was very unhappy with me, as was her mother”, Gavin later wrote. Irma remained in Washington during most of their marriage, which ended in divorce upon his return from the war.

In 1933, Gavin, who had no desire to become an instructor for new recruits, was posted to the 28th and 29th Infantry Regiment at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, under the command of General Lesley J. McNair. He spent most of his free time in, as he called it, the “excellent library” of this fort, while the other soldiers spent most of their time partying, shooting, and playing polo. One author in particular impressed Gavin: J. F. C. Fuller. Gavin said about him: “[He] saw clearly the implications of machines, weapons, gasoline, oil, tanks and airplanes. I read with avidity all of his writings.”

In 1936, Gavin was posted to the Philippines. While there, he became very concerned about the US ability to counter possible Japanese plans for expansion. The 20,000 soldiers stationed there were badly equipped. In the book Paratrooper: The Life of Gen. James M. Gavin, he is quoted as saying, “Our weapons and equipment were no better than those used in World War I”. After a year and a half in the Philippines, he returned to Washington with his family and served with the 3rd Infantry Division in the Vancouver Barracks. Gavin was promoted to captain and held his first command position as commanding officer of K Company of the 7th Infantry Regiment.

While stationed at Fort Ord, California, he received an injury to his right eye during a sports match. Gavin feared that this would end his military career, and he visited a physician in Monterey, California. The physician diagnosed a retinal detachment, and recommended an eye patch for 90 days. Gavin decided to rely on his eye healing by itself to hide the injury.

Gavin began training at the new Parachute School at Fort Benning in August 1941. After graduating in August, he served in an experimental unit. His first command was as a captain and the commanding officer of C Company of the newly established 503rd Parachute Infantry Battalion.

Gavin’s friends William T. Ryder, commander of airborne training, and William P. Yarborough, communications officer of the Provisional Airborne Group, convinced Colonel William C. Lee to let Gavin develop the tactics and basic rules of airborne combat. Lee followed up on this recommendation, and made Gavin his operations and training officer (S-3). On October 16, 1941, Gavin was promoted to major.

One of Gavin’s first priorities was determining how airborne troops could be used most effectively. His first action was writing FM 31-30: Tactics and Technique of Air-Borne Troops. He used information about Soviet and German experiences with paratroopers and glider troops, and also used his own experience in tactics and warfare. The manual contained information about tactics, but also about the organization of the paratroopers, what kind of operations they could execute, and what they would need to execute their task effectively. Later, when Gavin was asked what made his career take off so fast, he would answer, “I wrote the book”.

In February 1942, shortly after the United States entered World War II, Gavin took a condensed course at the US Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, which qualified him to serve on the staff of a division. He returned to the Provisional Airborne Group and was tasked with building up an airborne division. In the spring of 1942, Gavin and Lee went to Army Headquarters in Washington, D.C., to discuss the order of battle for the first US airborne division. The 82nd Infantry Division, then stationed at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, and commanded by Major General Omar Bradley, was selected to be converted into the first American airborne division and subsequently became the 82nd Airborne Division. Command of the 82nd went to Major General Matthew Ridgway. Lieutenant General Lesley J. McNair’s influence led to the division’s initial composition of two glider infantry regiments and one parachute infantry regiment, with organic parachute and glider artillery and other support units.

In August 1942, Gavin became the commanding officer of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment (505th PIR) at Fort Benning which had been activated shortly before on July 6. He was, aged just 35, promoted to colonel shortly thereafter. Gavin built this regiment from the ground up. He led his troops on long marches and realistic training sessions, creating the training missions himself and leading the marches personally. He also placed great value on having his officers “the first out of the airplane door and the last in the chow line”. This practice has continued to and with present-day US airborne units. After months of training, Gavin had the regiment tested one last time:

“As we neared our time to leave, on the way to war, I had an exercise that required them to leave our barracks area at 7:00 P.M. and march all night to an area near the town of Cottonwood, Alabama, a march about 23 miles. There we maneuvered all day and in effect we seized and held an airhead. We broke up the exercise about 8:00 P.M. and started the troopers back by another route through dense pine forest, by way of backwoods roads. About 11:00 P.M., we went into bivouac. After about one hour’s sleep, the troopers were awakened to resume the march. […] In 36 hours the regiment had marched well over 50 miles, maneuvered and seized an airhead and defended it from counterattack while carrying full combat loads and living off reserve rations.”

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Angolan Rebel 1970s era 60mm Inert Display Mortar from Angolan Civil War Original Items

Uncategorized

Australian WWII Owen MK1 Machine Carbine SMG Custom Fabricated Replica with Sling Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Band of Brothers ORIGINAL GERMAN WWII Le. F.H. 18 10.5cm ARTILLERY PIECE Original Items

Uncategorized

Armoured Fighting Vehicles of the World: AFVs of World War One (Hardcover Book) New Made Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized