Original British WWI Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5a Left Upper Wing Partial Roundel Skin Original Items

$ 1.895,00 $ 473,75

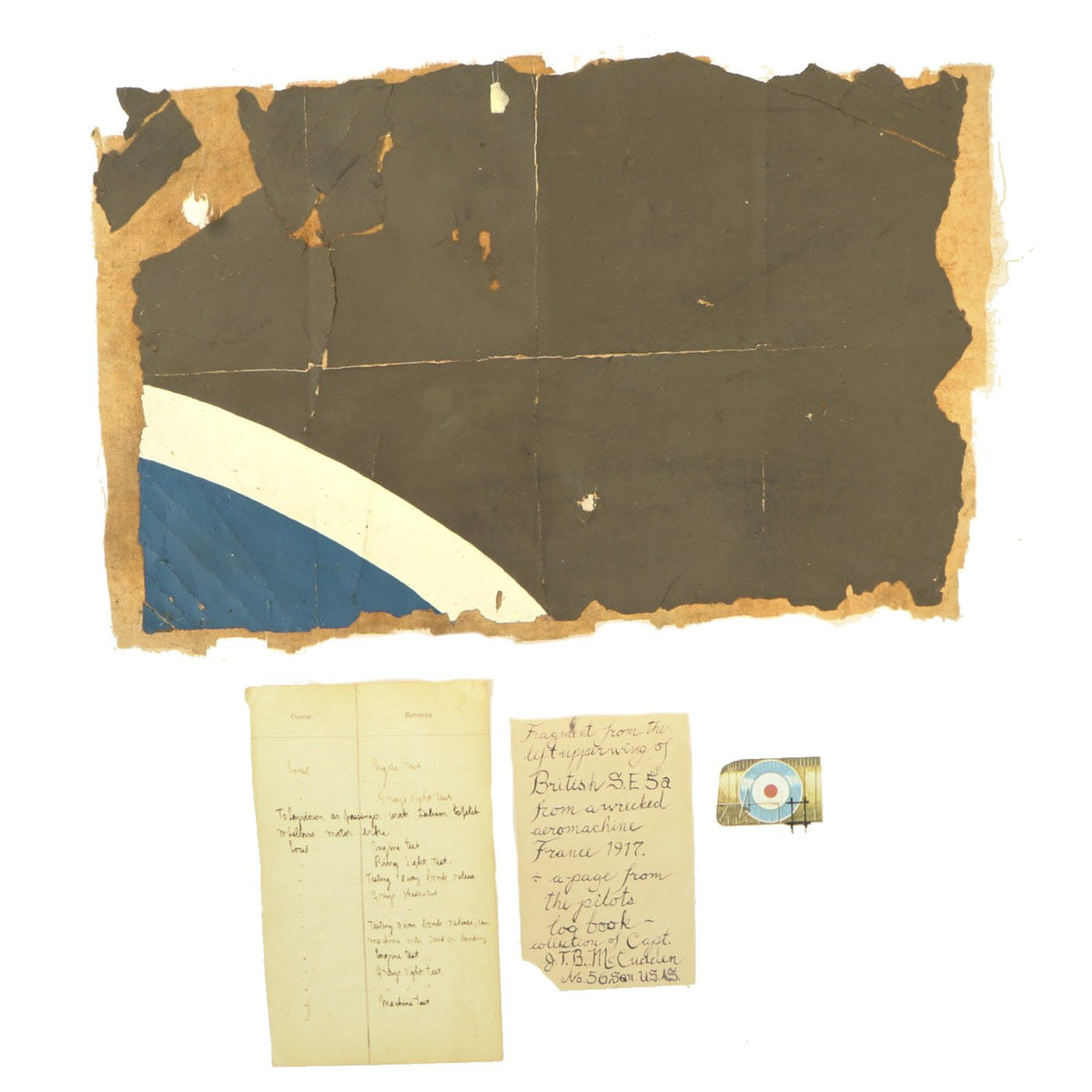

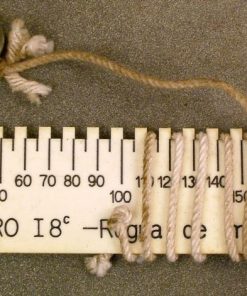

Original Item: One-of-a-kind. This is a 16″ x 10″ section of hand painted canvas airplane fuselage covering from a World War One British Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5A air craft. Along with the skin is a handwritten note that reads:

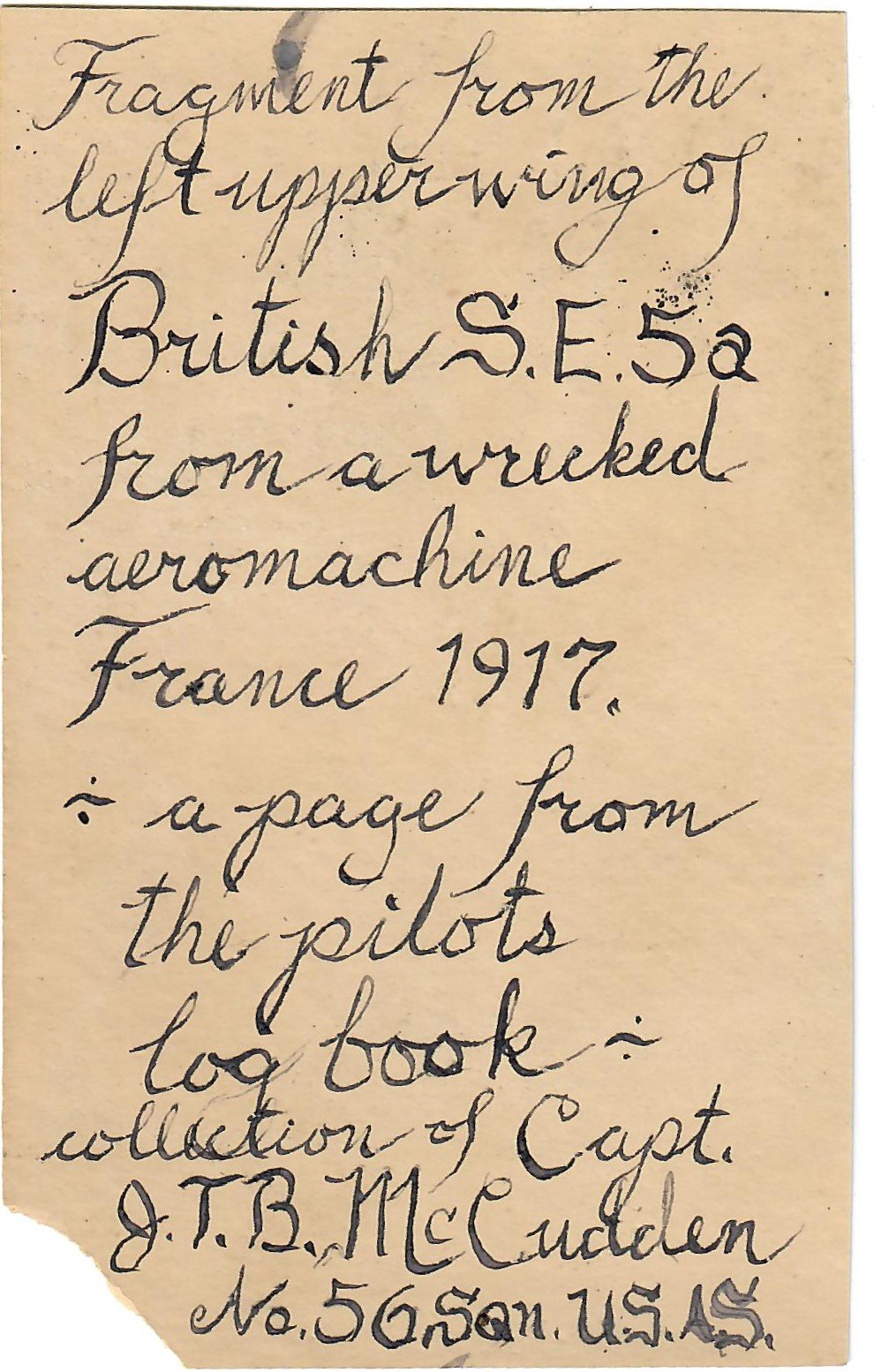

Fragment from left upper wing of British Royal Flying Corps (RFC) S.E. 5a from a wrecked aeromachine – France 1917 – and a page from he pilots log book -Collection of Capt. J.T.B. McCudden No. 56. Sqn. U.S.A.S.

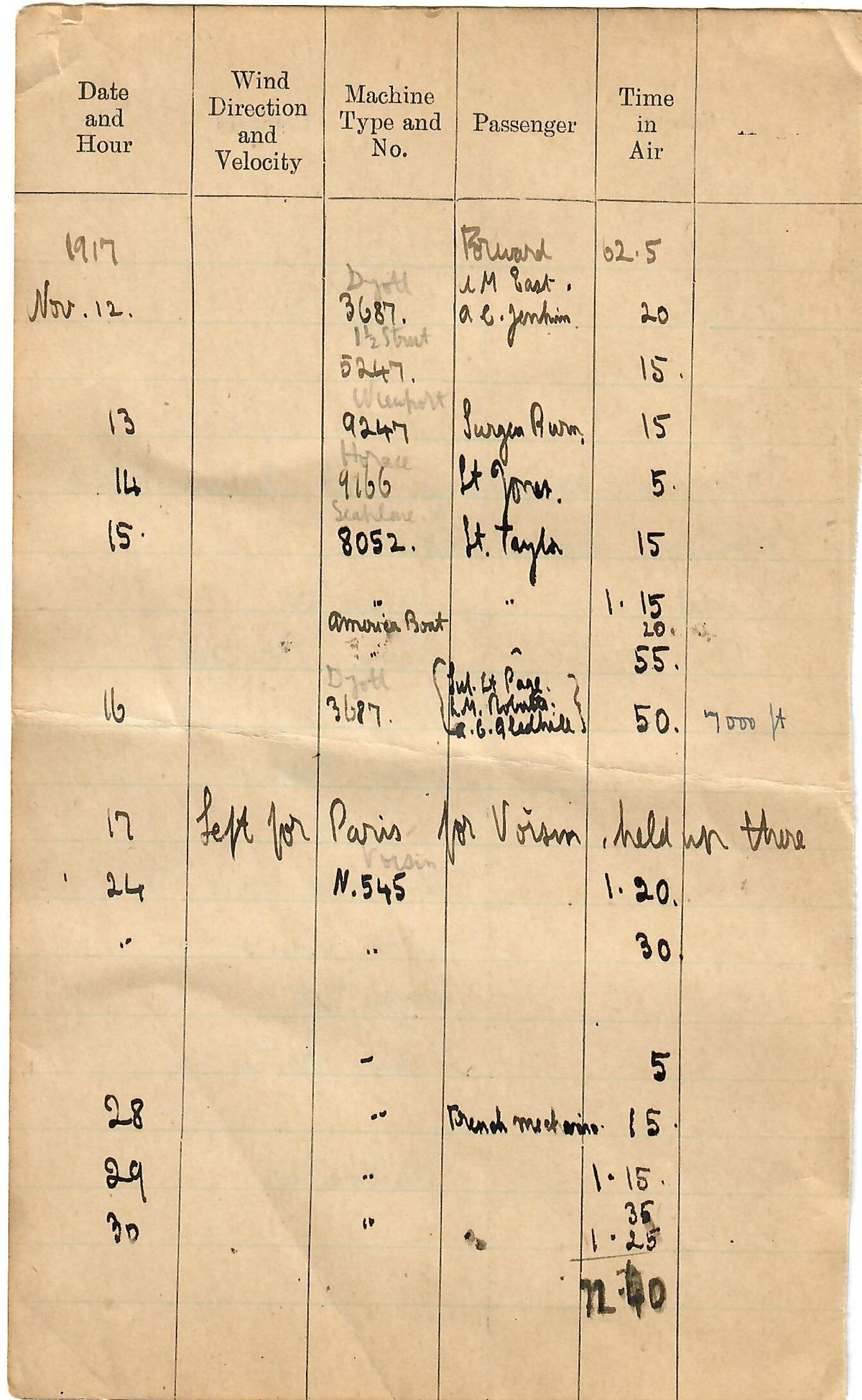

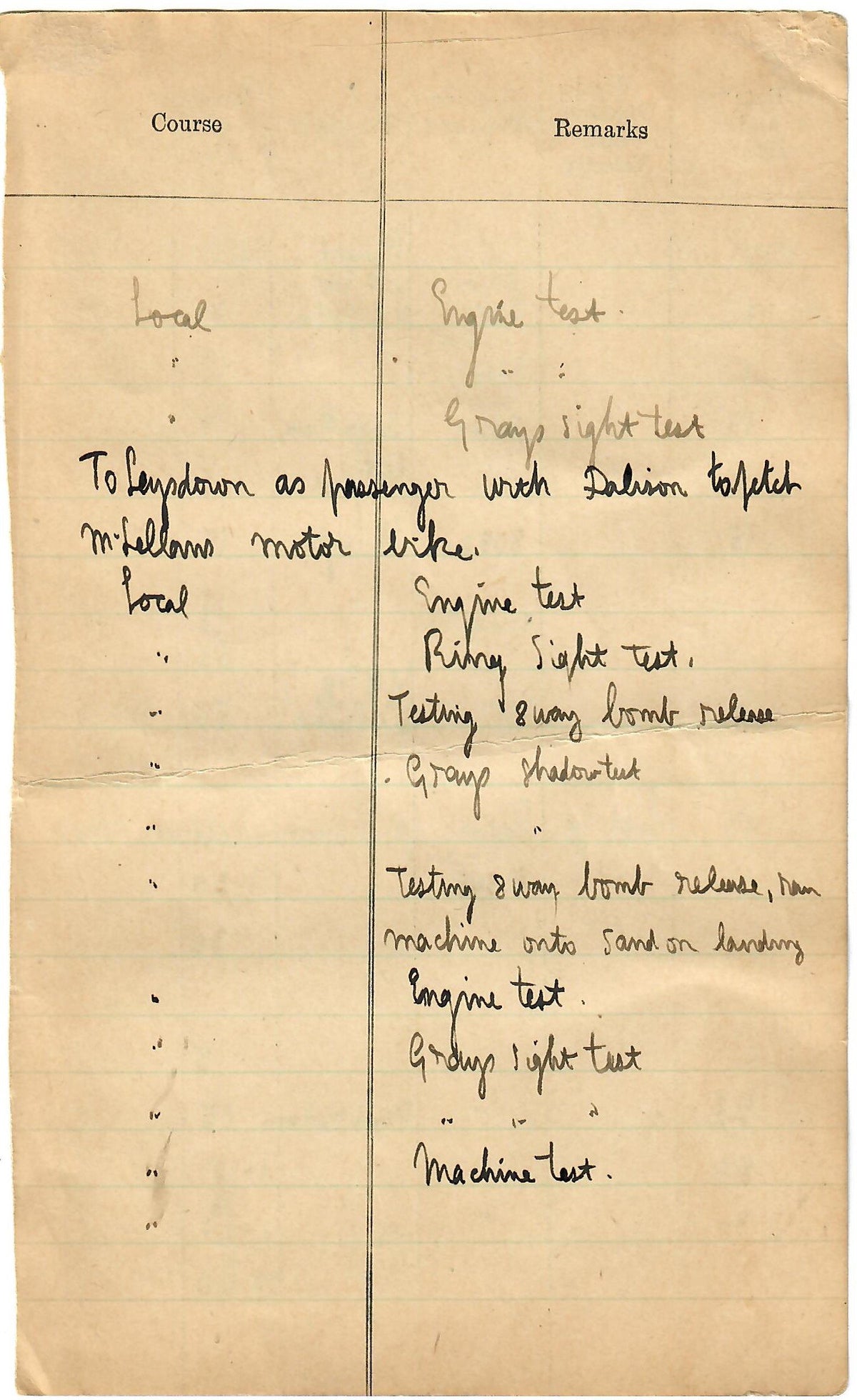

Also included is a page from a pilots log book dated November 1917. We do not know if this piece was from McCudden’s plane or just part of his personal collection. We offer it as we receive it, but there is no doubt that the skin, piolts log page are original to WW1.

James Thomas Byford McCudden, VC, DSO & Bar, MC & Bar, MM (28 March 1895 – 9 July 1918) was a British flying ace of the First World War and among the most highly decorated airmen in British military history.

Born in 1895 to a middle class family with military traditions, McCudden joined the Royal Engineers in 1910. Having an interest in mechanics he transferred to the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) in 1913 at which time he first came into regular contact with aircraft. At the outbreak of war in 1914 he flew as an observer before training as a fighter pilot in 1916.

McCudden claimed his first victory in September 1916. He claimed his fifth victory—making him an ace—on 15 February 1917. For the next six months he served as an instructor and flew defensive patrols over London. He returned to the frontline in summer 1917. That same year he dispatched a further 31 enemy aircraft while claiming multiple victories in one day on 11 occasions.

With his six British medals and one French, McCudden received more awards for gallantry than any other airman of British nationality serving in the First World War. He was also one of the longest serving. By 1918, in part due to a campaign by the Daily Mail newspaper, McCudden became one of the most famous airmen in the British Isles.

At his death he had achieved 57 aerial victories, placing him seventh on the list of the war’s most successful aces. Just under two-thirds of his victims can be identified by name. This is possible since, unlike other Allied aces, a substantial proportion of McCudden’s claims were made over Allied-held territory. The majority of his successes were achieved with 56 Squadron RFC and all but five fell while McCudden was flying the S.E.5a.

On 9 July 1918, McCudden was killed in a flying accident when his aircraft crashed following possible engine failure. His rank at the time of his death was major, a significant achievement for a man who had begun his career in the RFC as an air mechanic. McCudden is buried at the British war cemetery at Beauvoir-Wavans.

The Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5 was a British biplane fighter aircraft of the First World War. It was developed at the Royal Aircraft Factory by a team consisting of Henry Folland, John Kenworthy and Major Frank Goodden. It was one of the fastest aircraft of the war, while being both stable and relatively manoeuvrable. According to aviation author Robert Jackson, the S.E.5 was: “the nimble fighter that has since been described as the ‘Spitfire of World War One'”.

In most respects the S.E.5 had superior performance to the rival Sopwith Camel, although it was less immediately responsive to the controls. Problems with its Hispano-Suiza engine, particularly the geared-output H-S 8B-powered early versions, meant that there was a chronic shortage of the type until well into 1918. Thus, while the first examples had reached the Western Front before the Camel, there were fewer squadrons equipped with the S.E.5 than with the Sopwith fighter.

Together with the Camel, the S.E.5 was instrumental in regaining allied air superiority in mid-1917 and maintaining it for the rest of the war, ensuring there was no repetition of “Bloody April” 1917 when losses in the Royal Flying Corps were much heavier than in the Luftstreitkräfte. The S.E.5s remained in RAF service for some time following the Armistice that ended the conflict; some were transferred to various overseas military operators, while a number were also adopted by civilian operators.

Only 77 original S.E.5 aircraft had been completed prior to production settling upon an improved model, designated as the S.E.5a. The initial models of the S.E.5a differed from late production examples of the S.E.5 only in the type of engine installed – a geared 200 hp Hispano-Suiza 8ba, often turning a large “left-handed” clockwise-rotation four-bladed propeller (likely requiring the “lower” 0.585:1 reduction ratio of the H.S.8ba subtype), replacing the 150 hp H.S. 8A model. In total 5,265 S.E.5s were constructed by six manufacturers: Austin Motors (1,650), Air Navigation and Engineering Company (560), Curtiss (1), Martinsyde (258), the Royal Aircraft Factory (200), Vickers (2,164) and Wolseley Motors Limited (431).

Shortly following the American entry into World War I, plans were mooted for several American aircraft manufacturers to commence mass production of aircraft already in service with the Allied powers, one such fighter being the S.E.5. In addition to an order of “only” 38 Austin-built S.E.5a aircraft which were produced in Britain and assigned to the American Expeditionary Force to equip already-deployed USAAS squadrons serving with the AEF – despite evidence that some 200 S.E. 5a airframes were meant to be set-aside (inclusive of the 38 mentioned examples) for American use – the US Government issued multiple orders to the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company for the manufacture and delivery of around 1,000 S.E.5s to be produced in the United States. However, only one Curtiss-built aircraft would be completed prior to the end of the conflict, after which demand for the S.E.5 had effectively evaporated, production being quickly halted after a further 56 aircraft were assembled using already-delivered components.

At first, airframe construction outstripped the very limited supply of French-built Hispano-Suiza engines and squadrons earmarked to receive the new fighter had to soldier on with Airco DH 5s and Nieuport 24s until early 1918. The troublesome geared “-8b” model was prone to have serious gear reduction system problems, sometimes with the propeller (and even the entire gearbox on a very few occasions) separating from the engine and airframe in flight, a problem shared with the similarly-powered Sopwith Dolphin. The introduction of the 200 hp (149 kW) Wolseley Viper, a high-compression, direct-drive version of the Hispano-Suiza 8a made under licence by Wolseley Motors Limited, solved the S.E.5a’s engine problems and was promptly adopted as the type’s standard powerplant. A number of aircraft were subsequently converted to a two-seat configuration in order to serve as trainer aircraft.

The RAF underwent rapid expansion prior to and during the Second World War. Under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan of December 1939, the air forces of British Commonwealth countries trained and formed “Article XV squadrons” for service with RAF formations. Many individual personnel from these countries, and exiles from occupied Europe, also served with RAF squadrons. By the end of the war the Royal Canadian Air Force had contributed more than 30 squadrons to serve in RAF formations, similarly, approximately a quarter of Bomber Command’s personnel were Canadian. Additionally, the Royal Australian Air Force represented around nine percent of all RAF personnel who served in the European and Mediterranean theatres.

In the Battle of Britain in 1940, the RAF defended the skies over Britain against the numerically superior German Luftwaffe. In what is perhaps the most prolonged and complicated air campaign in history, the Battle of Britain contributed significantly to the delay and subsequent

The largest RAF effort during the war was the strategic bombing campaign against Germany by Bomber Command. While RAF bombing of Germany began almost immediately upon the outbreak of war, under the leadership of Air Chief Marshal Harris, these attacks became increasingly devastating from 1942 onward as new technology and greater numbers of superior aircraft became available. The RAF adopted night-time area bombing on German cities such as Hamburg and Dresden, and developed precision bombing techniques for specific operations, such as the “Dambusters” raid by No. 617 Squadron,[18] or the Amiens prison raid known as Operation Jericho.

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Australian WWII Owen MK1 Machine Carbine SMG Custom Fabricated Replica with Sling Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Band of Brothers ORIGINAL GERMAN WWII Le. F.H. 18 10.5cm ARTILLERY PIECE Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Angolan Rebel 1970s era 60mm Inert Display Mortar from Angolan Civil War Original Items

Uncategorized

Armoured Fighting Vehicles of the World: AFVs of World War One (Hardcover Book) New Made Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized