Original British WWI Lancaster Prisoner of War Camp German POW Art – Carved Beef Bone “Trench Art” Original Items

$ 275,00 $ 110,00

Original Items: Only One Available. Prisoners and surrender have been a central part of war since the dawn of time. Taking prisoners, at times for ransom, or as political punishment, has long been a concept that has come hand in hand with conflict.

While many see Prisoner of War (POW) camps as the perilous and nightmarish compounds of East Asia or Stalinist Russia, few are aware that a POW camp existed in Lancaster. The Prisoners Detention Camp was located in an old railway factory on Caton Road, Lancaster, England, which was put to use when the war began in 1914. It would eventually house more than 3,000 enemy ‘aliens’, prisoners and German POWs.

“Trench Art” is a genre of folk art comprised of items created in wartime, or from war materiel. It may be made by servicemen and women or by civilians, and is particularly associated with the First World War, which witnessed its greatest flowering.

Those who could not create had the opportunity to purchase. On every front, local civilians and prisoners of war (POWs) sought to turn the presence of souvenir-hungry soldiers to their own profit. For prisoners and internees held in camps, such creativity also mitigated the oppressive dreariness of their captivity.

Creating the bone carvings such as this example, was one of the ways in which the men passed their time at the camp and each bone, or carved pair of bones, are individual and unique.

Internees had to use whatever materials were readily available. Every week beef would have been sent to the camp to feed the 3,000 men. The remaining bones, left over from the cook houses, were one such material.

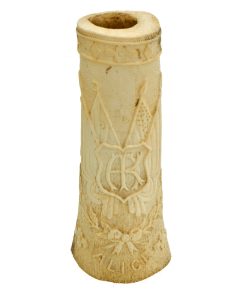

This example appears to have been made out of a beef bone, as mentioned before, every week beef was sent to the camp. The carvings feature images of 4 crossed flags over a shield, flags we believe to be from allied countries. Beneath the shield is the name Alice and was more than likely the name of a wife or girlfriend of a camp guard. Other carvings include what appears to be poppies, vines, diamonds and stars. On the back side of the bone is LANCASTER / CAMP / 1914-15. The carving stands as approximately 6 ¾” tall and is free of significant damage and cracks.

This unique one-of-a-kind piece of art comes ready to display!

Alien prisoners: The early days of the camp

As soon as the King’s Own Lancaster Regiment had left the city, plans were put in motion to turn the Lancaster Railway Carriage and Wagon Company into an internment camp.

Under the recent statutes of the 1907 Hague Convention, this was entirely legal when it came to international law, although the concept of internment appears a little sinister.

Internment is the imprisonment, commonly of people in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges.

While this may seem like the acts of a fascist government the term is used in relation to the imprisonment of enemy citizens during wartime as a preventative measure. Essentially, the camp was there to imprison German, Austrian and Ottoman nationals living in Britain, for fear that their national loyalties would lead to espionage or acts of terrorism against the British war effort.

A company of Royal Welsh Fusiliers arrived in Lancaster on August 20 and set about converting the factory into a camp. They were to take charge of the prisoners once they arrived.

The Lancaster Guardian reported on the changes to the building, stating that German prisoners would be in the city within days.

“A company of the 3rd Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers (Special Reserves) arrived to take charge of the prisoners,” the article reads.

“Barbed wire has been freely used around the walls of the building, and the railway enables trains to go straight to the works.”

Just four days after the Welsh Fusiliers set-up shop in Lancaster, a contingent of German prisoners arrived.

It was Monday, August 24, 1918, and the imprisoned had been transported by direct train to the factory, stopping at the sidings attached to the wagon works.

In the first week, 380 prisoners arrived, many of them German seamen whose boats had been in British ports when the war started.

In a further report entitled ‘Alien Prisoners in Lancaster’, the Lancaster Guardian paper claimed that: “The strictest precautions are taken to prevent escape or communication with the outside world.”

By mid-September the camp population had swelled alarmingly with more than 1,700 with prisoners arriving from Manchester, Newcastle and Carlisle.

Most prisoners were German or Austrian nationals, hosts of children and families were also detained in the camp, a stark contrast to the number of men who had originally arrived in the closing weeks of August.

By October the Royal Welsh Fusiliers had been replaced by men of the National Reserve.

Many of the new prison wardens were members of the King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment but too old for active service.

By this point the population of the Prisoners Detention Campo had shot up again.

“The population at the Prisoners Detention Camp has been increased latterly by the arrival of many Germans,” wrote the Lancaster Guardian.

“Many have been collected at Manchester. There are about 2,000 prisoners in the camp.”

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armoured Fighting Vehicles of the World: AFVs of World War One (Hardcover Book) New Made Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Angolan Rebel 1970s era 60mm Inert Display Mortar from Angolan Civil War Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Australian WWII Owen MK1 Machine Carbine SMG Custom Fabricated Replica with Sling Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized