Original British Victorian Rare Four Panel Colonial Pattern Sun Helmet Original Items

$ 795,00 $ 238,50

Original Item: Only One Available. Authorized in June of 1877 the regulation Foreign Service Helmet, was made of cork and covered in white cloth with a standard six seams. The style was worn throughout the empire, and this pattern remained in use until replaced by the Wolseley pattern helmet.

What we have here is the rare “four panel” version of the helmet, which has 4 panels and seams as opposed to the usual 6. The sun – or “pith” – helmet originated in India around the time of the Mutiny, but was only officially adopted in 1877 for general use by the British Army for use by all ranks serving in tropical locations including India and Africa. Known as the British Pattern 1877 Foreign Service Helmet, the helmet was made of cork and covered in white cloth.

This wonderful example of the British Foreign Service helmet dates to the late Victorian era, which saw this type used in many of Victoria’s “Little wars”. However, this style of helmet was also used in notable conflicts including the Zulu War, and also used in some earlier conflicts including the Abyssinian campaign and the Ashanti War.

This example offered in very good condition would have been issued standard infantry. It does not have a puggaree, just a strap to cover the liner pins, and the interior has a simple sweatband liner. The helmet has been re-blanco’d since the last time it saw service, so it is still a quite vibrant white. There are chin strap hooks on the inside, as well as a hook behind the vent, but no chin strap or scales are present. Also, there definitely have been helmet plates used on this helmet, but it is currently without one, as the last owner probably kept it as a memento before selling the helmet.

This is a fantastic and very rare totally original example of a rare variation of an iconic helmet. Ready to display!

The following article is a wonderful article eon the original of the British Pith helmet by renowned expert Peter Suciu:

Often dubbed the “pith helmet” or “sun helmet” by collectors, the British Foreign Service Helmet is one of the most evocative pieces of militaria from the Victorian Age. The cloth-covered, lightweight style of headgear that was used for the last quarter of the 19th century is as iconic to the era as the German steel helmet is to World War II. Nevertheless, it is a piece that has eluded any significant study. In fact, much of the origins of the helmet are still somewhat shrouded in mystery. Still, it is hard to think of those British soldiers in red coats facing off against the forces of the Mahdi or standing tall against the Zulu without their Foreign Service Helmets.

Throughout the first half of the 19th century, the British Army, as well as the military forces within the British East India Company, continued to wear uniforms that were only slightly changed from the Napoleonic Wars. This included the use of the shako, which remained popular throughout the armies of Europe. In the course of 60 years, the British used several different versions of shakos until the Home Service Helmet became the standard type of headgear for the British Army in 1878. However, this helmet was only intended for wear by units serving in the British Isles.

Events half way around the world played a major role in the headgear used by the British Army throughout the Empire. In particular, it was the Indian Mutiny of 1857.

British forces had been using the 1855 Pattern Shako as well as forage caps as the primary types of cover, but during the Mutiny, many officers acquired locally made helmets. These were often pressed cork, felt or canvas on a wicker frame. The exact origin of the helmets is uncertain, but it is likely that these were based on the earliest sun helmets provided for civilian use in the region.

When the helmets were first used by British Army or Company troops remains a question for speculation. It is worth noting that at least one painting from the era shows an officer of the 22nd Madras Native Infantry in 1856 wearing a high crested helmet that closely resembles the later style of the Foreign Service Helmets.

According to Indian Army Uniforms by W.Y. Carman, “The Indian Mutiny caused a great upheaval in accepted traditions and many changes towards a realistic uniform took place. Special headgear and warm weather garments were at last considered and officially approved.” Carman adds that this included the adoption of a tropical helmet for parade and ceremony use when the undress cap could not be worn.

The new permanent style of headgear was a cork helmet that was ordered for European officers in native regiments. Messrs. Hawkes and Co. of London, a company that may have had the original sole patent for making such headgear, was commissioned with the task of producing these first helmets.

Carman also writes that the helmet “was to be covered in white cloth with a regimental pugri (puggaree) and a gilt curb chin-chain.” From 1860, a cork helmet with an air vent at the top was issued to all regiments serving in India. It was this style of helmet that was used during the Abyssinian campaign in 1868 and in the following Ashanti War of 1874 in West Africa. In June 1877, a white helmet of similar design was officially authorized for wear by all ranks throughout the Empire.

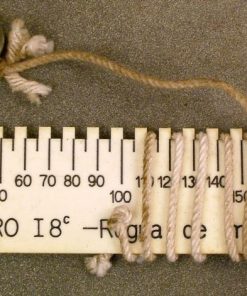

Labeled the “Foreign Service Helmet,” it was made of cork covered in white cloth with six seams. Peaks and sides were bound in white cloth, with a one-inch wide piece of cloth sewn around the headband above the peaks. This was covered by a puggaree in certain stations such as Hong Kong, Bermuda and Malta. The back peak measured 12″ from the crown to the edge. The front peak measured 10?”, but as these were handmade, variations are certainly encountered. A zinc button covered in white cloth was fitted to the top of the helmet.

KHAKI FEATURES

In addition to the helmets, the British forces in India also began to experiment with a new color of uniform. The famous “Red Coat” had seen widespread use since the days of Queen Anne nearly 150 years earlier. While the Victorian Age had been one of strict pomp and circumstance, the British Army was learning many costly lessons of war. Among these was that the bright white helmets may look good on parade, but they didn’t offer much in the way of camouflage.

The word “khaki” is Persian for “dust.” While serving in India, it was common for officers to attempt to break up the white color of helmets, as well as other white garments with the use of mud, tea, coffee, tobacco juice and curry powder. The results varied greatly, and by 1884 a patented dyestuff produced a fast “khaki” dye. It wasn’t until the second Afghan War in 1885 that a full khaki uniform replaced the red uniforms and white helmets. But because the helmet was often a private purchase item, many continued to be produced in white. Many officers purchased a white helmet and relied on a khaki cover, rather than having to purchase both a white and a khaki helmet. For this reason, it isn’t uncommon to find Foreign Service Helmets from much later than 1885 that are white in appearance.

In 1877, helmets were authorized to have a puggaree, the cloth wrap around the outer headband of the helmet, for station in Malta, India, Ceylon, Hong Kong, the Straits Settlements, the West Indies and Bermuda, St. Helena, Canada, West Africa and the Cape. The purpose of this cotton cloth wrapping was to help keep the helmet cool. Exactly how well this worked is left to debate. Based on period photos and surviving examples, it seems that considerable license was exercised by troops on overseas service, especially in South Africa, the Sudan and Egypt. There are many surviving examples of helmets with and without puggarees, but the 1900 Dress Regulations authorized the use of puggarees for all stations after the Army Order 83 of 1896.

Depending on the location where the helmet was used, a helmet curtain may have been made available to provide shade to the neck. This wrapped around the helmet and was tied from the front. Because the helmet curtain was not permanently attached, few examples have survived. An original helmet curtain must be considered extremely rare.

HELMET BADGES AND FITTINGS

One major misconception of the Foreign Service Helmet is that these all had the unit plates on the front. No doubt, this is due to movies such as “Zulu,” starring Michael Caine and Stanley Baker. But in fact, most of the Foreign Service Helmets never were fitted with helmet plates or any form of badges while being used by the British Army, and almost certainly not on campaign.

Part of the confusion is that colonial units, including the Natal Mounted Police, Natal Carbineers, Durban Mounted Rifles and Transvaal Range rs did wear plates, and more often spikes. The spike, when fitted into an acanthus leaf base, screwed into the same threads as the zinc button. Both the plates and spikes were typically issued in white metal or brass, and examples of each are encountered.

The chin strap used in the field is another interest that has continued to spark debate among collectors. “I am lead to believe that brass chin scales and a brass spike were only worn on parade,” says British helmet collector Steve Vernon. There are numerous photos that do suggest that for parade, British officers, especially in the years immediately following the introduction of the helmet, may have adopted the tendency to wear a spike and chin scales. This would be in keeping with the style that the officers grew accustomed to, considering that the newly adopted Home Service Helmet featured a brass spike and chin scales. But outside of the parade grounds, the spike certainly wasn’t business as usual for most officers. “In the field the chin scales were switched for a leather chin strap and the brass spike replaced with a covered zinc button which screwed into the spike’s base.

And while the British Army did not typically wear spikes or plates, the same rules did not seem to apply to the British Marines units, who wore a spike–or a ball for Marine Artillery units–with the regimental-pattern helmet plate. It was more common for units of the British Army, especially in the later decades of the 19th century, to adorn the unit insignia on the left hand side of the helmet. This was typically a unit’s cloth patch that was removed from the shoulder strap and either tucked into the puggaree or sewn to it.

By the end of the 19th century, the Foreign Service Helmet was in use throughout the Empire. By most reports it was, on average, liked by the troops. Enlisted men and NCOs were supplied with a helmet and often, a cover, while officers had to purchase their own helmets.

As with the Home Service Helmets, several manufacturers produced the Foreign Service Helmets. Thus, the collector may encounter subtle–and even not so subtle–differences in design. The primary manufacturers of these helmets are believed to be the same makers of the Home Service Helmet and included Hawkes & Company of Piccadilly, London; Humphreys & Crook of Haymarket, London; J.B. Johnstone of Saville St., London, and Dawson St., Dublin; H. Lehmann of Aldershot; and Samuel Gardner & Co of Clifford St., London. It is curious that a helmet in the collection of one of the authors was made by the aforementioned Hawkes & Co., but the label touts the firm as the “sole manufacturer”!

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armored Burgonet Helmet & Polearm from Scottish Castle Leith Hall Circa 1700 Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Angolan Rebel 1970s era 60mm Inert Display Mortar from Angolan Civil War Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized