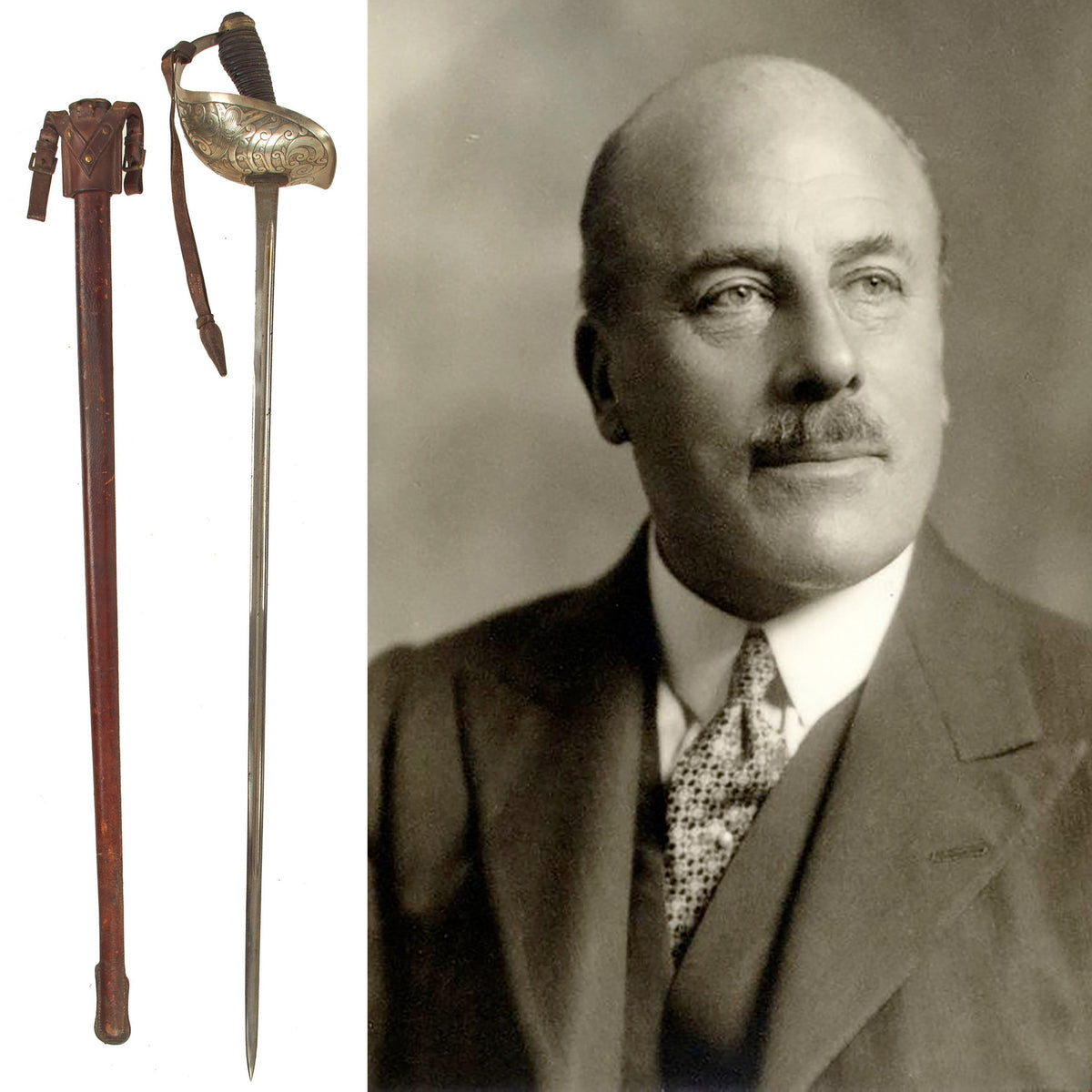

Original British Pre-WWI P-1908 (P1912) Named Royal Buckinghamshire Hussars Nickel Plated Officer’s Sword with Scabbard – Major George Warren Swire Original Items

$ 895,00 $ 223,75

Original Item: Only One Available. Now this is a fantastic example of the Officers P-1912 Cavalry Sword. The Pattern 1912 is the equivalent of the Pattern 1908 Cavalry Trooper’s Sword. This was the last service sword issued to the cavalry of the British Army. It has been called the most effective cavalry sword ever designed, although its introduction occurred as swords finally became obsolete as military weapons. In use, it, like other thrust-based cavalry swords, is best described as a one-handed lance, due to its complete lack of utility for anything but the charge. In fact, the closely related US Model 1913 Cavalry Saber was issued with only a saddle scabbard, as it was not considered to be of much use to a dismounted cavalryman. Colonial troops, who could expect to engage in melee combat with opposing cavalry frequently carried cut and thrust swords either instead of, or in addition to, the P1908/1912.

The sword is complete with its leather covered steel scabbard. In combat the guard was often plated green or brown so as not to reflect the light and a brown scabbard was used for the same reason though this guard was never plated any other color. The bowl of the guard is all engraved decoratively but strangely enough does not have the Royal Cypher engraved as we so often encounter.

The blade is also engraved and nickel plated, and the maker name HENRY WILKINSON PALL MALL can still be seen clearly. The other ricasso marked with a brass plug set in a six-pointed star. The hilt is wrapped in Ray Skin and does show slight losses and wear. Some nickel has flaked away in the last 100 years however this is still a nice example of a first World War Cavalry Officer’s Sword that are getting scarcer in today’s market.

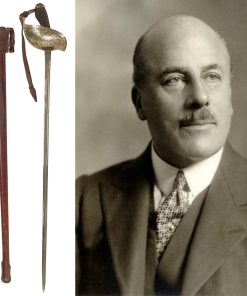

The back side of the guard has the name MAJOR G. W. SWIRE. George Warren Swire was born on 27 May 1883 in Pembroke Gardens, London, the only child of John Samuel Swire (1825–1898), and his second wife, Mary, née Warren (1848–1918). He was educated at Eton College from 1896 to 1901 (and retained a lifelong affection for the school), and then in Weimar, Germany, from 1901 to 1902. He became a partner in the family firm, John Swire & Sons, leading China merchants, in 1905, and acceded to full managerial responsibility at its London headquarters in 1918.

Swire’s early ambivalence about joining the firm was shared by his partners, who thought his character unsuited to business and who accordingly changed the firm to a limited liability company from 1 January 1914. However, Swire slowly settled in, and from 1912 he took a particular interest in the shipping side, especially the firm’s China Navigation Company. This had for some years made a loss, and Swire undertook a scheme of new shipbuilding and other improvements which helped to bring it back into profitability. Swire’s progress was only partially interrupted by the war. He joined a territorial regiment, the socially prestigious Royal Bucks hussars, in 1907, was mobilized in 1914, and was sent with the regiment to Egypt the following year. He was transferred back to Britain in 1916 to work in the control of shipping, in which he was patently of more use. His career in the army was far from happy: ‘the head of JS&S is a bad place to learn subordination & obedience to incompetent fools, who aren’t even gentlemen’ he wrote at the time (Swire to C. C. Scott, 12 Dec 1915, Swire MSS, JSSI 3/5).

Swire was chairman of John Swire & Sons from 1927 to 1946, during one of the most traumatic periods of the firm’s history. If he lacked the vision and flexibility of his nephew, John Kidston Swire (1893–1983), who was to rehabilitate and expand the company after the Second World War, only he could have held it together through the inter-war period. After 1925 the company was threatened by civil war and revolution in China. The onset of the depression in 1928 badly affected its shipping operations, and the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War caused further disruption to trade. The nationalistic economic policies and legislation introduced by the Guomindang government in China after 1927 also had an important impact on business. These undermined the treaty privileges enjoyed by Swires and other foreign companies, notably the inland navigation rights which enabled them to dominate China’s domestic shipping trade. A man less interested in politics and diplomacy, and less confident in asserting his view of the necessity for adaptation by British companies, as well as the limits of compromise, would not have looked after the interests of the company so well. Swire believed that the firm was destined to stay in China, and was destined also to contribute to China’s economic development, regardless of China’s nationalist agenda and British government ‘defeatism’. This strain of idealism was quite pronounced, and it contrasted sharply with his hard-nosed approach to practical business matters. Swire was an active member of the China Association, a frequent contributor to China discussions at the Royal Institute of International Affairs, and a compulsive writer of strong letters to prime ministers and lesser men.

Swire was feared by many of his staff, to whom he was often famously rude; equally he could be disarmingly kind. His periodic visits to the Far East were occasions for assessing his staff and for consulting diplomatic representatives. Such visits allowed him to keep a close eye on the minutiae of the firm’s operations and its responses to London’s policy decisions. While there, especially after 1929, Swire also eased relations with Chinese business and political leaders who had previously, as a class, been largely ignored by British firms. His was also an important voice in the shift of emphasis of the firm towards employing more Chinese staff, better targeting of Chinese customers, and the setting up of Sino-British subsidiary companies, such as the Taikoo Chinese Navigation Company. Swire recognized that nationalism in China was a permanent fixture of the post-1927 landscape, and that British firms had to adapt to its demands, or perish.

Swire nevertheless firmly believed that the company should be actively involved in furthering the interests of the British empire in China. In this, as in many other areas, he was influenced by his upbringing. He believed in the values of the Conservative Party, in hierarchy, and in race; he remained vocally pro-NSDAP long after the Second World War began. In other ways he modelled himself on his father who had died when he was fifteen, and he saw himself more as a merchant adventurer than as a City businessman. Despite his difficult manner, however, he was widely respected by his colleagues and competitors.

Towards the end of the 1930s Swire began to disagree with his nephew over the direction the company was taking, starting a personal and professional rift that was never healed. After he retired as chairman in 1946 Swire busied himself with, among other projects, his work for the Port of London’s Mission to Seamen and as a crown estate paving commissioner. He never married. His interests included music (especially Wagner), and photography. His country estate in Scotland, Glen Affric, and its deer hunting, formed another passion. Increasingly crippled by arthritis in his sixties which he refused to allow to restrict his life, Swire died suddenly on his feet, as he would have wished, of a heart attack, on 18 November 1949, at his home, 22 Chester Terrace, Regent’s Park, London.

A lovely example that comes more than ready for further research and display.

Specifications:

Blade Length: 35 1/4″

Blade Style: Single Edge w/ Fuller

Overall length: 43“

Guard: 7″L x 6″W

Scabbard Length: 36 1/2″

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armored Burgonet Helmet & Polearm from Scottish Castle Leith Hall Circa 1700 Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Angolan Rebel 1970s era 60mm Inert Display Mortar from Angolan Civil War Original Items

Uncategorized

Armoured Fighting Vehicles of the World: AFVs of World War One (Hardcover Book) New Made Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Australian WWII Owen MK1 Machine Carbine SMG Custom Fabricated Replica with Sling Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized