Original British Pattern 1796 Light Cavalry Saber with Scabbard Original Items

$ 895,00 $ 223,75

Original Item: Only One Available: The Pattern 1796 Light Cavalry Sabre is a sword that was used primarily by British Light Dragoons and hussars, and King’s German Legion light cavalry during the Napoleonic Wars. It was adopted by the Prussians (as the 1811 pattern or “Blücher sabre”) and used by Portuguese and Spanish cavalry.

This example is offered in as found condition, the blade shows weathered acceptance markings and is rust stained. The grip is grooved wood in good condition and is supported by the correct iron single bar stirrup guard. Still carried in the original very large iron scabbard with two hanging rings, the surface covered in old pitting. Being of such large proportions it is most certainly entirely correct for the period of 1796-1815.

Background

During the early part of the French Revolutionary War, the British Army launched an expeditionary force into Flanders. With the invading army was a young captain of the 2nd Dragoon Guards, serving as a brigade major, John Gaspard Le Marchant. Le Marchant noted the lack of professional skill displayed by the horsemen and the clumsy design of the heavy, over-long swords then in use and decided to do something about it. Among many other things Le Marchant did to improve the cavalry, he designed, in collaboration with the Birmingham sword cutler Henry Osborn, a new sabre. This was adopted by the British Army as the Pattern 1796 Light Cavalry Sabre.

Design

An eastern influence can be detected in the blade form, and Le Marchant is recorded as saying that the “blades of the Turks, Mamalukes, Moors and Hungarians [were] preferable to any other”. The blade profile is similar to some examples of the Indian tulwar, and expert opinion has commented upon this. This similarity prompted some Indian armourers to re-hilt old 1796 pattern blades as tulwars later in the 19th century.

Trooper pattern sabre

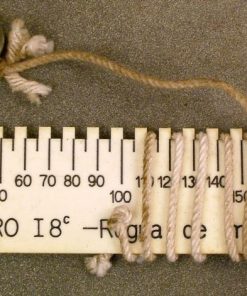

The 1796 sabre had a pronounced curve, making the kind of slashing attacks used in cavalry actions decidedly easier. Even cavalrymen trained to use the thrust, as the French were, in the confusion of a melee often reverted to instinctive hacking, which the 1796 accommodated. Its blade, unlike other European sabres of the period, widened near the point. This affected balance, but made slashes far more brutal; its action in the cut has been compared to a modern bacon slicer. It is said that this vicious design prompted unofficial complaints from French officers, but this is unconfirmed. The blade of the light cavalry sabre was from 32.5 to 33 inches in length and had a single broad fuller on each side. The sabre was lighter and easier to use than its heavy cavalry counterpart, the pattern 1796 Heavy Cavalry Sword, which had a less ‘scientific’ design. The hilt was of the simple ‘stirrup’ form with a single iron knucklebow and quillon, so as to be free of unnecessary weight; the intention of this was to make the sabre usable by all cavalrymen, not solely the largest and strongest. In common with the contemporary heavy cavalry sword, the iron back piece of the grip had ears which were riveted through the tang of the blade to give the hilt and blade a very secure connection. The grip was of ridged wood covered in leather. It was carried in an iron scabbard, with wooden liners, and hung from the waist via sword-belt slings attached to two loose suspension rings.

Officer’s sabers

Officers carried fighting swords very similar in form to those of the trooper version, though they tended to be lighter in weight and show evidence of higher levels of finish and workmanship. Officers stationed in India sometimes had the hilts and scabbards of their swords silvered as a protection against the high humidity of the Monsoon season. Unlike the officers of the heavy cavalry, light cavalry officers did not have a pattern dress sword. As a result of this there were many swords made which copied elements of the 1796 pattern design but incorporated a high degree of decoration, such as blue and gilt or frost-etched blades, and gilt-bronze hilts. At their most showy, sabres with ivory grips and lion’s-head pommels are not unknown. These swords were obviously primarily intended for dress rather than battle.

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armored Burgonet Helmet & Polearm from Scottish Castle Leith Hall Circa 1700 Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized