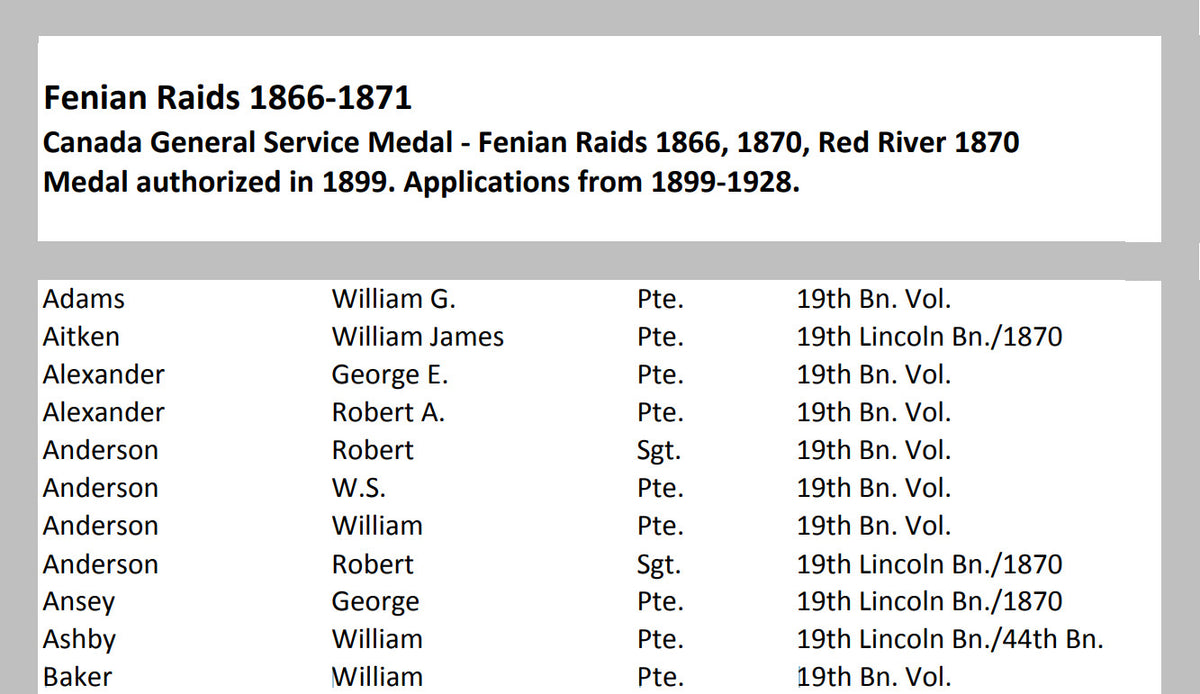

Original British North America Fenian Troubles Rim Engraved Canadian General Service Medal With 1866 Fenian Raid Clasp – Private William Baker, Stratford Volunteer Rifle Company Original Items

$ 595,00 $ 178,50

Original Item: Only One Available. The Fenian raids were a series of incursions carried out by the Fenian Brotherhood, an Irish republican organization based in the United States, on military fortifications, customs posts and other targets in Canada (then part of British North America) in 1866, and again from 1870 to 1871. A number of separate incursions by the Fenian Brotherhood into Canada were undertaken to bring pressure on the British government to withdraw from Ireland, although none of these raids achieved their aims.

This medal is a fine example of one of only 13,000 General Service Medals that were awarded with the Fenian Raid 1866 Clasp. The Canada General Service Medal was a campaign medal awarded by the Canadian Government to both Imperial and Canadian forces for duties related to the Fenian raids between 1866 and 1871. The medal was initially issued in 1899 and had to be applied for. The application period was later extended to 1907, then to 1928.

With late applications, 17,623 medals were awarded, including 15,300 to members of Canadian units.

The medal, 1.4 inches (36 mm) in diameter, is silver and has a plain straight swivel suspender. The obverse bears the head of Queen Victoria with the legend VICTORIA REGINA ET IMPERATRIX, while the reverse depicts the ensign of Canada surrounded by a wreath of maple leaves with the word CANADA above.

The recipient’s name, rank and unit appear on the rim of the medal. A number of different impressed and engraved styles were used, reflecting that the medal was awarded over a long period of time.

This one is engraved with:

PTE. W. BAKER. STRATFORD. R. CO.

The 1.25 inches (32 mm) wide ribbon consists of three equal stripes of red, white and red. In 1943 the same ribbon was adopted for the Canada Medal.

The overall condition is excellent with minor tarnishing and age toning present on the ribbon. There is no significant damage present.

Comes more than ready for further research and display.

In 1838, the Third Regiment of Huron was organized in the territory which is now the south part of Perth County, Ontario. This was a paper organization of the compulsory militia, to which every able-bodied male citizen in theory belonged. It did not have equipment, did not train, and while it continued to exist after the voluntary militia was formed, it was distinct from the volunteers.

The Stratford Volunteer Rifle Company was formed in 1856, elected its own officers, and carried on entirely at the expense of its members for two years, before it was officially recognized in 1858.

In response to the Fenian Raids, a temporary battalion-sized composite unit was formed in 1866 at Thorold, Ontario. It consisted of companies from Stratford, Chatham, Ingersoll, St. Thomas and Guelph.

A general order of the Militia Department of the Province of Canada, dated 14 September 1866 authorized a regimental headquarters. Robert Service of Stratford was promoted to Lt Col and appointed to command. The Stratford Volunteer Rifle Company became No. 1 Company of the regiment. Other companies were in Listowel and St. Marys

The principle of Militia units was voluntary service and year-round training while carrying on with civilian life. The Perth Regiment maintained this principle throughout its peacetime service.

Fenian Raids

Early raids (1866)

Dedham

The Dedham, Massachusetts chapter of the Fenian Brotherhood, which had offices in the Norfolk House, hosted a meeting at Temperance Hall in which a raid into Canada was organized. John R. Bullard, a recent Harvard Law School graduate, was elected moderator of the meeting and, having been swept up in his own sudden importance and fever of the meeting, ended his animated speech by asking “Who would be the first man to come forward and pledge himself to go to Canada and help free Ireland?” The first of the roughly dozen men to sign the “enlistment papers” were Patrick Donohoe and Thomas Golden. Thomas Brennan said he could not participate, but donated $50 to the cause. The meeting ended with the group singing “The Wearing of the Green.” The raid was a failure. Some of the men got as far as St. Albans, Vermont, but none made it to Canada. A few were arrested and some had to send home for money.

New Brunswick

Led by John O’Mahony, this Fenian raid occurred in April 1866, at Campobello Island, New Brunswick. A Fenian Brotherhood war party of over 700 members arrived at the Maine shore opposite the island intending to seize Campobello from the British. Royal Navy officer Charles Hastings Doyle, stationed at Halifax, Nova Scotia, responded decisively. On 17 April 1866, he left Halifax with several warships carrying over 700 British soldiers and proceeded to Passamaquoddy Bay, where the Fenian force was concentrated. This show of force by Doyle discouraged the Fenians, and they dispersed. The invasion reinforced the idea of protection for New Brunswick by joining with the British North American colonies of Nova Scotia, and the United Province of Canada, formerly Upper Canada (now Ontario) and Lower Canada (Quebec), to form the Dominion of Canada.

Canada West

After the Campobello raid, the “Presidential faction” led by Fenian founders James Stephens and John O’Mahony focused more on fundraising for rebels in Ireland. The more militant “Senate Faction” led by William R. Roberts believed that even a marginally successful invasion of the Province of Canada or other parts of British North America would provide them with leverage in their efforts. After the failure of the April attempt to raid New Brunswick, which had been blessed by O’Mahony, the Senate Faction implemented their own plan for invading Canada. Drafted by the senate “Secretary for War” General T. W. Sweeny, a distinguished former Union Army officer, the plan called for multiple invasions at points in Canada West (now southern Ontario) and Canada East (now southern Quebec) intended to cut Canada West off from Canada East and possible British reinforcements from there. Key to the plan was a diversionary attack at Fort Erie from Buffalo, New York, meant to draw troops away from Toronto in a feigned strike at the nearby Welland Canal system. This was the only Fenian attack, other than the Quebec raid several days later, that was launched in June 1866.

About 1000 to 1300 Fenians crossed the Niagara River in the first 14 hours of June 1 under Colonel John O’Neill. Sabotaged by Fenians in its crew, the U.S. Navy’s side-wheel gunboat USS Michigan did not begin intercepting Fenian reinforcements until 2:15 p.m.—14 hours after Owen Starr’s advance party had crossed the river ahead of O’Neill’s main force. Once the USS Michigan was deployed, O’Neill’s force in the Niagara Region was cut off from further supplies and reinforcements.

After assembling with other units from Canada and traveling all night, Canadian troops advanced into a well-laid ambush by approximately 600–700 Fenians the next morning north of Ridgeway, a small hamlet west of Fort Erie. (The Fenian strength at Ridgeway had been reduced by desertions and deployments of Fenians in other locations in the area overnight.)

Canadian Militia troops at the Battle of Ridgeway consisted of inexperienced volunteers with no more than basic drill training but armed with Enfield rifled muskets equal to the armaments of the Fenians. A single company of the Queen’s Own Rifles of Toronto had been armed the day before on their ferry crossing from Toronto with state-of-the-art seven-shot Spencer repeating rifles, but had not had an opportunity to practice with them and were issued with only 28 rounds per man. The Fenians were mostly battle-hardened American Civil War veterans, armed with weapons procured from leftover war supplies, either Enfield rifled muskets or the comparable Springfield.

Members of the Canadian Militia were ambushed by the Fenians at the Battle of Ridgeway in June 1866.

The opposing forces exchanged volleys for about two hours, before a series of command errors threw the Canadians into confusion. The Fenians took advantage of it by launching a bayonet charge that broke the inexperienced Canadian ranks. Seven Canadians were killed on the battlefield, two died shortly afterwards from wounds, and four later died of wounds or disease while on service; ninety-four more were wounded or disabled by disease. Ten Fenians were killed and sixteen wounded.

A funeral for soldiers killed during the Fenian attacks in Canada East, 30 June 1866.

After the battle, the Canadians retreated to Port Colborne, at the Lake Erie end of the Welland Canal. The Fenians rested briefly at Ridgeway, before returning to Fort Erie. Another encounter, the Battle of Fort Erie, followed that saw several Canadians severely wounded and the surrender of a large group of local Canadian Militia who had moved into the Fenian rear. After considering the inability of reinforcements to cross the river and the approach of large numbers of Canadian Militia and British soldiers, the remaining Fenians released the Canadian prisoners and returned to Buffalo early in the morning of June 3. They were intercepted by the gunboat Michigan and surrendered to the United States Navy.

The traditional historical narrative alleges that the turning point in the Battle of Ridgeway was when Fenian cavalry was erroneously reported and the Canadian Militia ordered to form squares, the standard tactic for infantry to repel cavalry. When the mistake was recognized, an attempt was made to reform in column; being too close to the Fenian lines, it failed. In his 2011 history of Ridgeway, however, historian Peter Vronsky argues the explanation was not as simple as that. Prior to the formation of the square, confusion had already broken out when a unit of the Queen’s Own Rifles mistook three arriving companies from the 13th Battalion of The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry for British troops. When the Queen’s Own Rifles began retiring to give the field to what they thought were British Army units, the 13th Battalion mistook this for a retreat, and began withdrawing themselves. At this moment that the infamous “form square” order was given, completing the debacle that was unfolding on the field.

A board of inquiry determined that allegations over the alleged misconduct of Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Booker (13th Battalion), on whom command of Canadian volunteers had devolved, had “not the slightest foundation for the unfavourable imputations cast upon him in the public prints”. Nevertheless, the charges dogged Booker for the rest of his life. A second board of inquiry into the battle at Fort Erie exonerated Lieutenant-Colonel J. Stoughton Dennis, Brigade Major of the Fifth Military District, although the President of the Board of Inquiry, Colonel George T. Denison, differed from his colleagues on several key points.

Five days after the start of the invasion, U. S. President Andrew Johnson issued a proclamation requiring enforcement of the neutrality laws, guaranteeing the Fenian invasion could not continue. Generals Ulysses S. Grant and General George Meade went to Buffalo, New York to inspect the situation. Following instructions from Grant, Meade issued strict orders to prevent anyone from violating the border. Grant then proceeded to St. Louis. Meade, finding that the battles were over and the Fenian army interned in Buffalo, went to Ogdensburg, New York, to oversee the situation in the St. Lawrence River area. The U.S. Army was then instructed to seize all Fenian weapons and ammunition and prevent more border crossings. Further instructions on 7 June 1866 were to arrest anyone who appeared to be a Fenian.

Fenian commander Brigadier-General Thomas William Sweeny was arrested by the United States government for violating American neutrality. Nevertheless, he was soon released and served in the United States Army until he retired in 1870.

Canada East

After the invasion of Canada West failed, the Fenians decided to concentrate their efforts on Canada East; however, the U.S. government had begun to impede Fenian activities, and arrested many Fenian leaders. The Fenians soon saw their plans begin to fade. General Samuel Spear of the Fenians managed to escape arrest, and, on June 7, Spear and his 1000 men marched into Canadian territory, achieving occupancy of Pigeon Hill, Frelighsburg, St. Armand and Stanbridge. At this point the Canadian government had done little to defend the border, but on June 8 Canadian forces arrived at Pigeon Hill and the Fenians, who were low on arms, ammunition and supplies, promptly surrendered, ending the raid on Canada East.

Timothy O’Hea was awarded the Victoria Cross for actions he took at Danville, Canada East, on June 9, 1866, at about the time of the Pigeon Hill Raid. Although only about 23 years old, O’Hea, a private in the 1st Battalion of the Rifle Brigade stationed in Canada, saw the threat posed by a burning railway car containing ammunition and fought the blaze single-handedly for an hour, saving the lives of many in the area.

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Band of Brothers ORIGINAL GERMAN WWII Le. F.H. 18 10.5cm ARTILLERY PIECE Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Australian WWII Owen MK1 Machine Carbine SMG Custom Fabricated Replica with Sling Original Items