Original British Napoleonic Wars Royal Navy Shaving Mug – Glazed Earthenware Original Items

$ 295,00 $ 118,00

Original Item: Only One Available. This is a very lovely example of a British Royal Navy sailor’s shaving mug from the Napoleonic Wars. Earthenware is glazed or unglazed non vitreous pottery that has normally been fired below 1,200 °C (2,190 °F). Basic earthenware, often called terracotta, absorbs liquids such as water. However, earthenware can be made impervious to liquids by coating it with a ceramic glaze, like this example, which the great majority of modern domestic earthenware has. The main other important types of pottery are porcelain, bone china, and stoneware, all fired at high enough temperatures to vitrify.

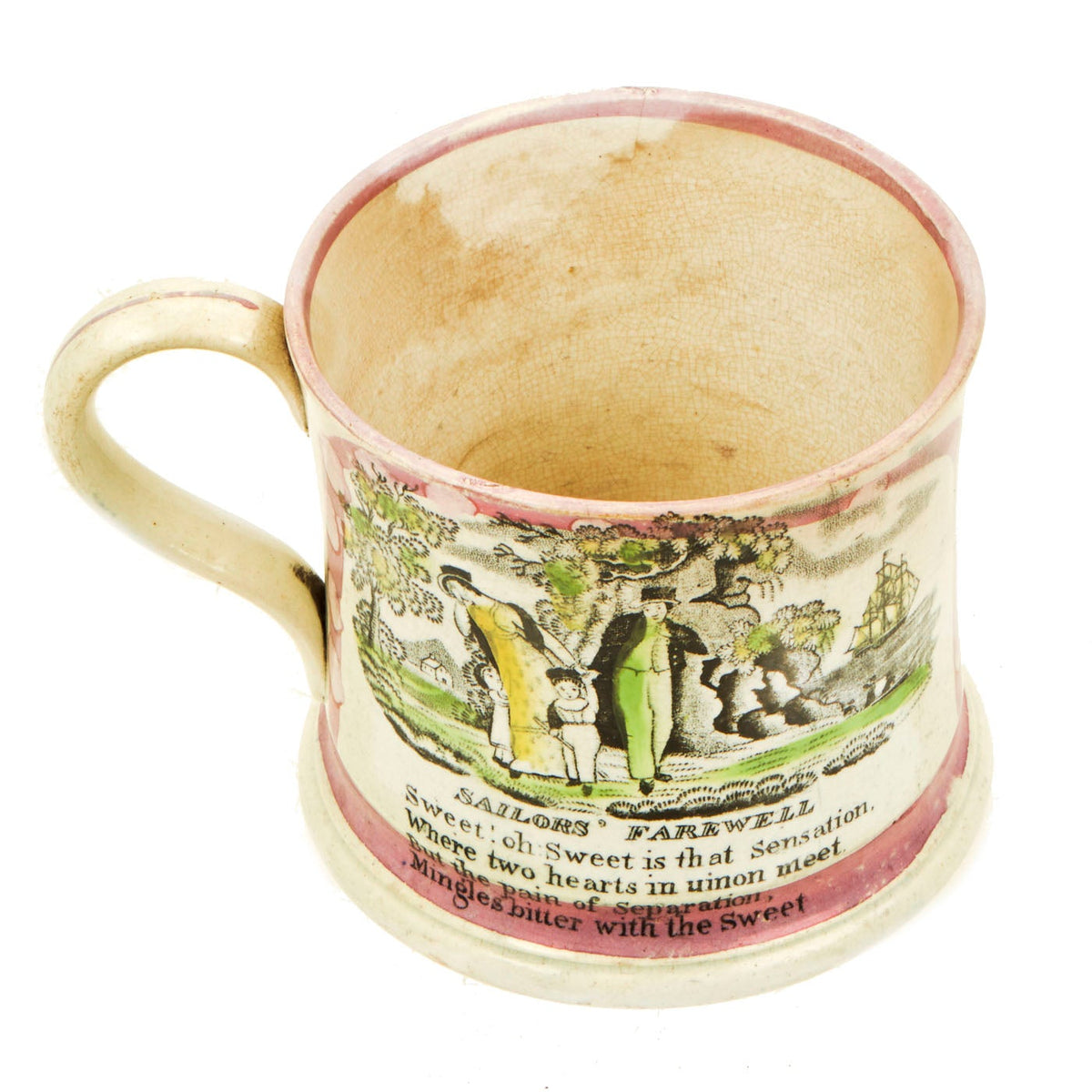

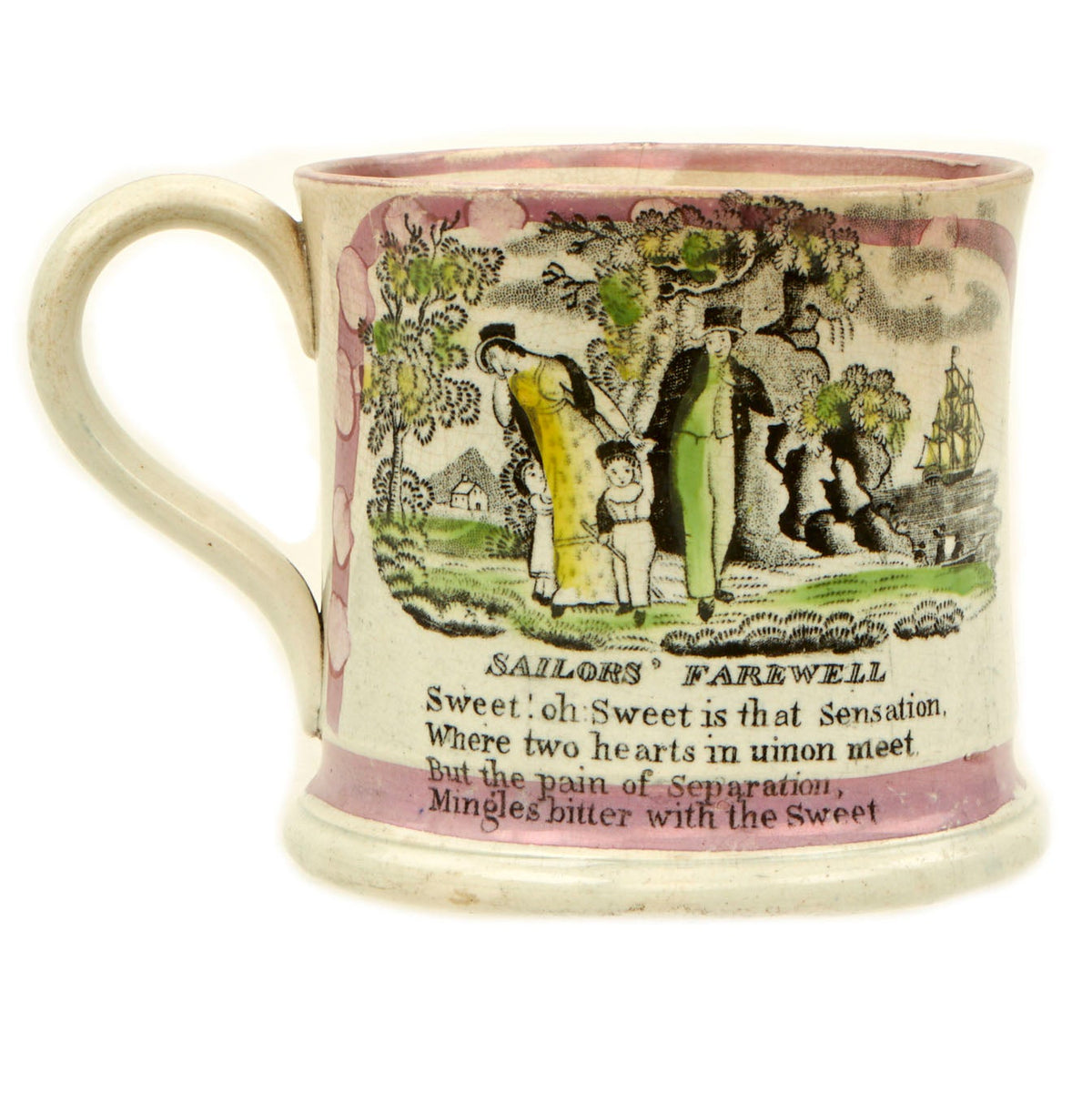

This example depicts images and poetic sentiments related to the Royal Navy. Both sides have sentiments as well as naval type images with a sailor saying goodbye to his family, ships and floral motifs.

The one side shows on image of a family consisting of a father, mother and two children standing on the coastline together with ships in the water. The woman looks upset hugging the children as the man appears to be walking away. The poem is titled “Sailors’ Farewell” and is as follows:

“Sweet! oh: Sweet is that Sensation,

Where two hearts in union meet,

‘But the pain of Separation,

Mingles bitter with the sweet”

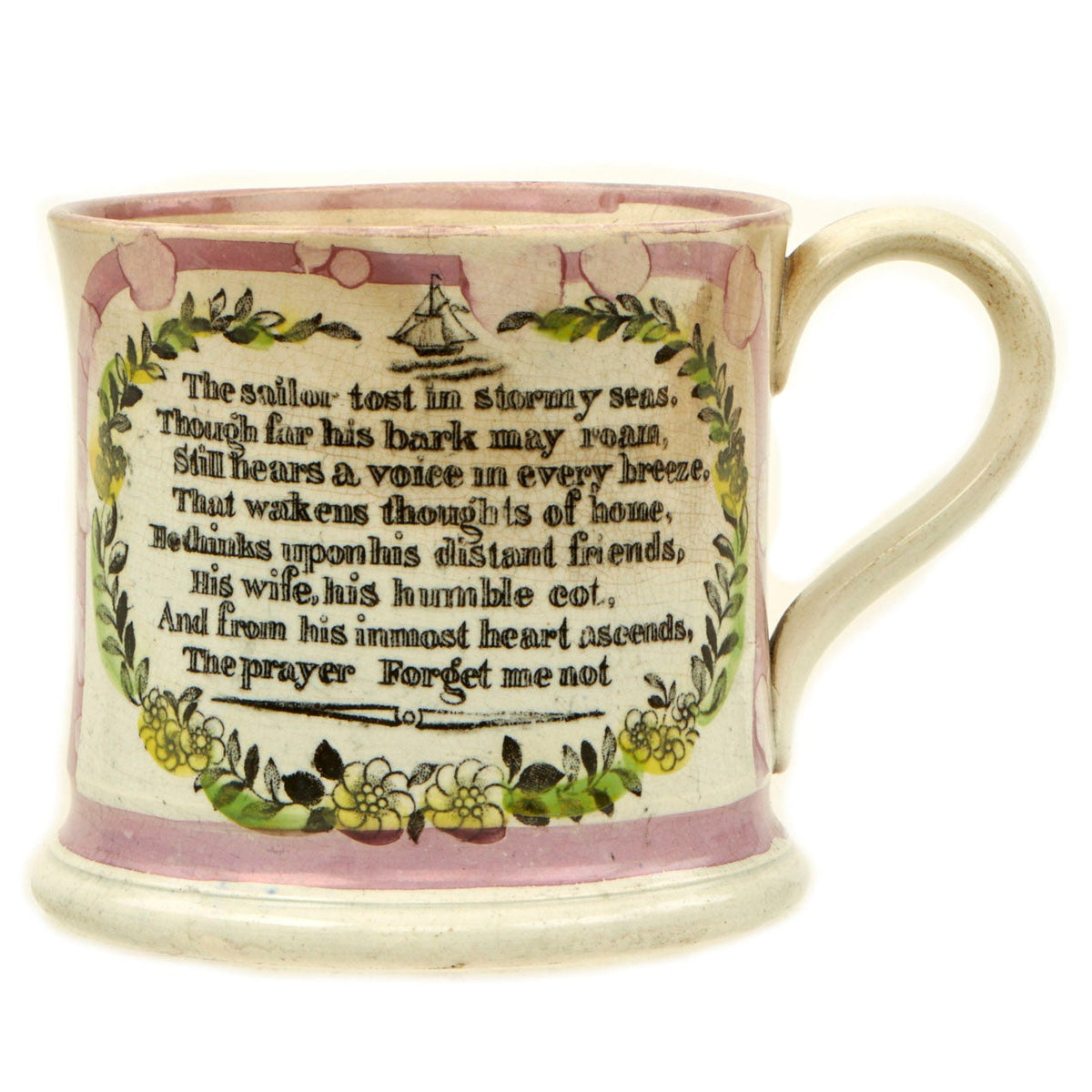

The other side has another poem which is untitled and is bordered by a laurels with a ship at the top. The poem, also Naval related, is as followed:

“The sailor tost in the stormy seas,

Though for his bark may roam,

Still hears a voice in every breeze,

That wakens thoughts of home,

He thinks upon his distant friends,

His wife, his humble cot,

And from his inmost heart ascends,

The prayer Forget me not”

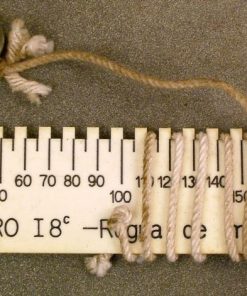

The mug has the expected cracks due to age and use but even after 200 years it’s still beautiful and would still be able to function as was intended originally. There are no chips, only the mentioned cracks which are superficial and appear to only be in the glaze.

Comes ready to be displayed in your Napoleonic Wars Royal Navy collections!

Between 1793 and 1815, Great Britain (later the United Kingdom) was the most constant of France’s enemies. Through its command of the sea, financial subsidies to allies on the European mainland, and active military intervention in the Peninsular War, Britain played the central role in Napoleon’s downfall even as all the other major powers switched back and forth.

With the execution of King Louis XVI in 1793, the French Revolution became a contest of ideologies between the conservative, royalist Kingdom of Great Britain and its allies and radical Republican France. Napoleon, who came to power in 1799, threatened invasion of Great Britain itself, and with it, a fate similar to the countries of continental Europe that his armies had overrun. The Napoleonic Wars were therefore ones in which the British invested all the money and energies it could raise. French ports were blockaded by the Royal Navy.

After a relatively quiet pause from 1801-1803, war resumed in Europe. Napoleon’s plans to invade Britain failed due to the inferiority of his navy, and in 1805, Lord Nelson’s fleet decisively defeated the French and Spanish at the Battle of Trafalgar, which was the last significant naval action of the Napoleonic Wars.

The series of naval and colonial conflicts, including a large number of minor naval actions, resembled those of the French Revolutionary Wars and the preceding centuries of European warfare. Conflicts in the Caribbean, and in particular the seizure of colonial bases and islands throughout the wars, could potentially have some effect upon the European conflict. The Napoleonic conflict had reached the point at which subsequent historians could talk of a “world war”. Only the Seven Years’ War offered a precedent for widespread conflict on such a scale.

Napoleon also attempted economic warfare against Britain, especially in the Berlin Decree of 1806. It forbade the import of British goods into European countries allied with or dependent upon France, and installed the Continental System in Europe. All connections were to be cut, even the mail. British merchants smuggled in many goods and the Continental System was not a powerful weapon of economic war. There was some damage to Britain, especially in 1808 and 1811, but its control of the oceans helped ameliorate the damage. Even more damage was done to the economies of France and its allies, which lost a useful trading partner. Angry governments gained an incentive to ignore the Continental System, which led to the weakening of Napoleon’s coalition.

The British army remained a minimal threat to France; the British standing army of just 220,000 at the height of the Napoleonic Wars hardly compared to France’s army of a million men—in addition to the armies of numerous allies and several hundred thousand national guardsmen that Napoleon could draft into the military if necessary. Although the Royal Navy effectively disrupted France’s extra-continental trade—both by seizing and threatening French shipping and by seizing French colonial possessions—it could do nothing about France’s trade with the major continental economies and posed little threat to French territory in Europe. In addition, France’s population and agricultural capacity far outstripped that of Britain.

Many in the French government believed that isolating Britain from the Continent would end its economic influence over Europe and isolate it. Though the French designed the Continental System to achieve this, it never succeeded in its objective. Britain possessed the greatest industrial capacity in Europe, and its mastery of the seas allowed it to build up considerable economic strength through trade to its possessions from its rapidly expanding new Empire. Britain’s command of the sea meant that France could never enjoy the peace necessary to consolidate its control over Europe, and it could threaten neither the home islands nor the main British colonies.

Sideshows like the Gunboat War against Denmark, the Walcheren Campaign against the Netherlands and the War of 1812 against the United States could not hurt Napoleon, but the Spanish uprising of 1808 at last permitted Britain to gain a foothold on the Continent. The Duke of Wellington and his army of British and Portuguese gradually pushed the French out of Spain and in early 1814, as Napoleon was being driven back in the east by the Prussians, Austrians, and Russians, Wellington invaded southern France. After Napoleon’s surrender and exile to the island of Elba, peace appeared to have returned, but when he escaped back into France in 1815, the British and their allies had to fight him again. The armies of Wellington and Von Blucher defeated Napoleon once and for all at the Battle of Waterloo.

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Australian WWII Owen MK1 Machine Carbine SMG Custom Fabricated Replica with Sling Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Angolan Rebel 1970s era 60mm Inert Display Mortar from Angolan Civil War Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized