Original British East India Company Named Pattern 1796 Naval Officer Saber by Osborn & Gunby – Circa 1810 Original Items

$ 5.995,00 $ 1.498,75

Original Item: One-of-a-kind. This is a stunning named example of a Presentation British Pattern 1796 Light Cavalry Officer’s Saber for a Naval Colonel in the East India Company, complete with its snake skin scabbard. The saber was manufactured by one of its originators, Henry Osborn, and is clearly marked on the blade:

OSBORN & GUNBY

SWORD CUTLERS

TO HIS MAJESTY

THE HONORABLE BOARD

OF ORDNANCE

& THE HONORABLE

EAST INDIA COMPANY

BIRMINGHAM

& PALL MALL LONDON

Henry Osborn was a Birmingham based manufacturer who produced a wide variety of military goods. Although best known for his swords, and the Pattern 1796 that he helped design, Osborn(e) was also listed as a Gun maker, silversmith, accouterment maker and hilt maker as well as a sword and dirk cutler. Osborn was born in 1756 and was apparently beginning to serve his apprenticeship to a master sword cutler by 1765, which he appears to have completed around 1784. In 1785, Osborn first appears in the Birmingham directories as a sword cutler, working in Brookhouse Lane, and by 1800 is also operating a manufactory on Bordesley Street, known as the Bordesley Street Mills. In 1802, Osborn opened a retail outlet in London at 82 Pall Mall Street. Around 1806, he partnered with John Gunby and from about 1806-1820 the business operated as Osborn & Gunby. In 1807, the London operation was renamed as well and by 1808 the Pall Mall retail outlet was also listed in the directories as Osborn & Gunby.

In 1819, the London retail shop moved to 48 Thames Street, where it would remain until its closure in 1838. The Osborn & Gunby partnership ended between 1820 and 1821 and by 1821 Osborn was again listed as the sole operator of his Birmingham and London establishments. In 1827, Henry Osborn died, and his son Thomas and widow Hannah took over the business, continuing to run it under the Henry Osborn name. In 1838, the London retail location was closed, and the Birmingham location was renamed for Thomas Osborn, under whose guidance it continued until 1849.

During his life Henry Osborn was appointed Sword Cutler & Accouterment Maker to His Majesty the King and His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales. He was also a founding member of the Loyal Birmingham Light Horse Volunteers, who served as a yeomanry home guard cavalry regiment during the darkest times of a potential French invasion of England, from 1797-1802. Among the other founders of the unit were several notable Birmingham arms makers of the period, including gunmakers & cutlers Thomas Ketland, James Wooley & William Sargant.

The scabbard throat is engraved with the retailer information in four lines:

OSBORN & GUNBY

SWORD CUTLERS

TO HIS MAJESTY

BIRMINGHAM

& PALL MALL LONDON

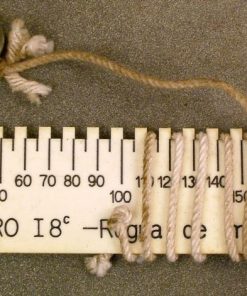

The blade of the saber measures 32 ¾”, which is in line with the “regulation” 32 ½”-33” length for the trooper’s saber. The overall length of the sword is 38”, including the 5” reverse-P guard hilt with a Lion’s Head pommel and wire bound ivory grip. The blade measures 1 5/8” wide at the ricasso and narrows then widens towards the tip. The blade is dramatically curved and is decorated with a 24″ etched panels with stands of arms, foliage, the arms of the East India company, Royal arms, mounted figures, the figure of Brittania, the East India Company Lion and the owners name COLONEL SENTTEGER.

The Lion’s Head hilt is of gilt brass with a grooved ivory grip applied on each side with a copper gilt plaque engraved with naval trophies and with nine turns of coiled wire. There are two languets each in the shape of a Heraldic Shield showing King George lll crown over a Fouled Anchor.

As noted, the saber remains in about VERY GOOD+ condition. The blade appears to be full-length with only some minor blunting to the tip noted. The metal has a medium pewter patina, with scattered light surface oxidation and discoloration. The blade retains most of the deep etching with some light wear and minor loss.

The original thick leather throat washer remains in place at the hilt to blade junction. The blade to hilt joint remains tight without any wobble or looseness noted. The scabbard, which may be a later replacement, is snake skin and remains in excellent condition.

Overall this is a fantastic example of a British East India company named office Pattern 1796 Saber, complete with scabbard. The saber was made by one of the most desirable British sword cutlers of the Napoleonic Era, Henry Osborn, the very man who helped to design it. The saber is well marked, as is the scabbard, and is very attractive.

Specifications:

Blade Length: 33″

Blade Style: Curved Single Edge

Overall length: 38“

Guard: 7″W x 4 3/4″L

Scabbard Length: 35 1/2″

In 1796, the British War Department adopted a newly designed saber for use by the Light Cavalry. This included the Hussars, the Light Dragoons and the Horse (Mounted) Artillery. John Gaspard Le Merchant, a British cavalry officer, designed the saber based upon his military experiences in the field. Le Merchant saw the inadequacies in the British Pattern 1788 cavalry saber design, as well as the failure of the accompanying tactics, while he was serving as a brigade major with the British Cavalry in Flanders, during the Low Countries campaign in the early years of the French Revolutionary Wars (1793-1795). Upon returning to England, he enlisted the aid of English cutler and sword maker Henry Osborn (some references spell the name with an “e” at the end, but Osborn blades are not so marked) and between them was born the Pattern 1796 Light Cavalry Saber. The saber had a curved blade with relatively short, slashing tip, referred to by some as a “hatchet” tip. The blade was typically between 32 ½” and 33” long and had a simple stirrup shaped iron guard with a pair of languets on either side of the guard to “trap” an enemy’s blade. The grip had a grooved wood core, which was wrapped with braided cord and then wrapped with leather, without an exterior wrap of wire as was typical of many sabers of the era. A pair of iron “ears” extended down from the backstrap on either side of the grip’s center, and a transverse pin reinforced the grip to backstrap attachment; strengthening it and keeping the grip from wobbling or working itself loose from the hilt. Le Merchant’s design was strictly for hacking and slashing, and not for thrusting, as the Pattern 1796 Heavy Cavalry saber was intended.

Le Merchant credited the sword designs of the Hungarians, Turks and Moors for his inspiration to create a heavily curved blade that actually got wider near the tip. As the saber was designed and balanced for hacking and slashing at an enemy, it was the last 10” or so of the blade, nearest the tip that saw the most use in combat, and that usually shows the most use on extant examples. This area was often sharpened to a near razor like edge, and period accounts have been known to compare the effect of the 1796 Light Cavalry saber upon its enemy to meat being assaulted by a giant slicer! Le Merchant not only designed the saber, but also the accompanying tactics, and taught that the saber should be used to strike at the head and arms of enemy cavalrymen, rather than to thrust at them.

British cavalryman George Farmer, who was serving with the 11thRegiment of Light Dragoons during the Peninsular Campaign against Napoleon, recalled one account of the effectiveness of the P1796 in combat. During a skirmish with French cavalry on the Guadiana River, Farmer remembered:

“Just then a French officer stooping over the body of one of his countrymen, who dropped the instant on his horse’s neck, delivered a thrust at poor Harry Wilson’s body; and delivered it effectually. I firmly believe that Wilson died on the instant yet, though he felt the sword in its progress, he, with characteristic self-command, kept his eye on the enemy in his front; and, raising himself in his stirrups, let fall upon the Frenchman’s head such a blow, that brass and skull parted before it, and the man’s head was cloven asunder to the chin. It was the most tremendous blow I ever beheld struck; and both he who gave, and his opponent who received it, dropped dead together. The brass helmet was afterwards examined by order of a French officer, who, as well as myself, was astonished at the exploit; and the cut was found to be as clean as if the sword had gone through a turnip, not so much as a dint being left on either side of it.”

The design was so successful and well received that the Prussian Pattern 1811 Blücher Saber was a nearly direct copy of Le Merchant’s design, and sabers based upon the P1796 would serve German cavalry well into the 20th century, and even during the First World War!

The saber was carried in a heavy iron scabbard that was supported by a pair of mounts with a pair of suspension rings. Often the sabers and scabbards that saw service with the British military were rack numbered, and today mixed numbered scabbards and sabers are quite common, as the swords were more likely to be lost on the field than the accompanying scabbards, and a similarly retrieved battlefield pick up usually replaced the lost sword. The Pattern 1796 Light Cavalry saber remained in use with the British cavalry for only a few years after the battle of Waterloo (June 18, 1815), and was officially replaced with the Pattern 1821 Light Cavalry saber, although the effectiveness and the popularity of the P1796 with the troopers resulted in the saber remaining in service for several decades after its official “replacement”, even seeing service as late as the Crimean War with some units, despite having been superseded by two different patterns (both the Pattern 1821 and Pattern 1853).

Not long after the development and adoption of the Pattern 1796 Light Cavalry Saber, Osborn modified the blade to create an officer’s pattern of the sword. This blade was more traditional at the end with less of a hatchet tip. It was tapered and pointed sufficiently to allow the saber to be used for thrusting as well. As British officers were required to provide their own uniforms and sidearms, an amazing amount of latitude was granted to officer’s sabers. As long as the sword conformed to the basic pattern, embellishments were allowed, with the imagination and the pocket book of the buyers being the only major constraints on the design. After the adoption of the Lion Pommel design for the Pattern 1803 Infantry Officer’s Sword, this motif became a popular one to incorporate into Pattern 1796 Light Cavalry Officer’s Sabers. Lion hilt P1796 sabers were not uncommon during the first quarter of the 19thcentury. The blades often were often of a variety of curvatures and lengths, again often at the whim of the officer himself. While the steel scabbards were appropriate and necessary in the saddle, often leather scabbards were acquired as well as the metal ones for wear when not mounted.

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Band of Brothers ORIGINAL GERMAN WWII Le. F.H. 18 10.5cm ARTILLERY PIECE Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Angolan Rebel 1970s era 60mm Inert Display Mortar from Angolan Civil War Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Australian WWII Owen MK1 Machine Carbine SMG Custom Fabricated Replica with Sling Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armored Burgonet Helmet & Polearm from Scottish Castle Leith Hall Circa 1700 Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized