Original 1960s Japanese Self-Defense Force Type 2 “Fangs” Pattern Camouflage Shirt Original Items

$ 225,00 $ 90,00

Original Item: Only One Available. This is a scarce Type 2 Japanese Defense Force Camouflage Shirt, which was used from 1965 to 1980. These are seldom found on the market, as the JSDF is rather small, and are generally used until worn out and unserviceable.

This 1960s example still shows excellent vibrant coloration. It is in good condition, showing signs of honest field use (a few field repairs here and there). The zipper still functions flawlessly. Inside there is a tag with the original owner’s name written on.

This would serve as an excellent example of Post WWII Japanese Camouflage to add to an international camouflage collection! Ready for Display!

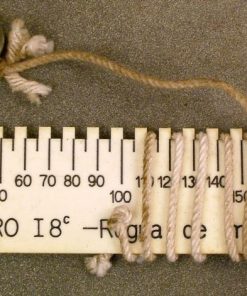

Approximate Measurements:

Collar to shoulder: 8″

Shoulder to sleeve: 20.5”

Shoulder to shoulder: 14.5”

Chest width: 18″

Waist width: 19″

Hip width: 19″

Front length: 28.5″

Japanese Defense Force Camouflage:

The first contemporary camouflage pattern of Japanese design was introduced circa 1965 on the “Type 1 Camouflage Uniform.” The design, having black, reddish-brown, and medium green woodland shapes on a pale green background, was initially issued to members of the 1st Airborne Brigade and is often associated with that unit. Some Japanese sources have referred to the design colloquially as “Hokkaido,” “Northern,” and “Kunai” camouflage, the latter of which may refer to a medieval trowel or hand-tool with a spike on one end. By 1980, a second version of the camouflage pattern had been printed. The early version of this camouflage design has earned the nickname “gapped” due to the appearance of gaps between some of the shapes in the design not present in the later version; however, close examination reveals that, in fact, there are distintive differences in the shapes found within the early (1st) and later (2nd) versions. By the early 1980s, the pattern would see use by conventional Japanese ground units. Within Western collecting circles, the pattern is sometimes referred to as “Fang” pattern. This design became outdated in 1992 with the introduction of the “dots” design.

The Japanese Self-Defense Force:

Japan surrendered to the Allied Powers on August 15, 1945, and officially exchanged instruments of surrender in Tokyo Bay on September 2, after which Japan underwent a U.S.-led military occupation for seven years, until April 28, 1952. The Occupation was commanded by American general Douglas MacArthur, whose office was designated the Supreme Command for the Allied Powers (SCAP). In the initial phase of the Occupation, from 1945 to 1946, SCAP had pursued an ambitious program of social and political reform, designed to ensure that Japan would never again be a threat to world peace.

Among other reforms, SCAP worked with Japanese leaders to completely disband the Japanese military. In addition, SCAP sought to unravel the wartime Japanese police state by breaking up the national police force into small American-style police forces controlled at the local level.SCAP also sought to empower previously marginalized groups that it believed would have a moderating effect on future militarism, legalizing the Communist and Socialist parties and encouraging the formation of labor unions.[15] The crowning achievement of the first phase of the Occupation was the promulgation at SCAP’s behest in 1947 of a new Constitution of Japan. Most famously Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution explicitly disavows war as an instrument of state policy and promises that Japan will never maintain a military.

By this time however, Cold War tensions were already ramping up in Europe, where the Sovietoccupation of Eastern European countries led Winston Churchill to give his 1946 “Iron Curtain” speech, as well as in Asia, where the tide was turning in favor of the Communists in the Chinese Civil War.[15] These shifts in the geo-political environment led to a profound shift in U.S. government and Allied Occupation thinking about Japan, and rather than focusing on punishing and weakening Japan for its wartime transgressions, the focus shifted to rebuilding and strengthening Japan as a potential ally in the emerging global Cold War, leading to a reversal of many earlier Occupation policies that has come to be known as the “Reverse Course.” As part of this shift, MacArthur and other U.S. leaders began to question the wisdom of Japan’s unilateral renunciation of all military capabilities, a renunciation that they themselves had so recently insisted upon. These sentiments were intensified in 1950 as Occupation troops began to be moved to the Korean War (1950–53) theater. This left Japan defenseless and vulnerable, and caused U.S. and Japanese conservative leaders alike to become increasingly aware of a pressing need to enter a mutual defense relationship with the United States in order to guarantee Japan’s external security in the absence of a Japanese military. Meanwhile, on the Japanese domestic front, rampant inflation, continuing hunger and poverty, and the rapid expansion of leftist parties and labor unions led Occupation authorities to fear that Japan was ripe for communist exploitation or even a communist revolution and to believe that conservative and anti-communist forces in Japan needed to be strengthened. Accordingly, in July 1950, Occupation authorities authorized the establishment of a National Police Reserve(警察予備隊, Keisatsu-yobitai), consisting of 75,000 men equipped with light infantry weapons.[16][17] In 1952, the Coastal Safety Force (海上警備隊, Kaijō Keibitai), the waterborne counterpart of NPR, was also founded.

The Security Treaty Between the United States and Japan was signed on 8 September 1951, and came into force on 28 April 1952. Perhaps surprisingly, while the treaty allowed the United States to maintain military bases in Japan, it did not obligate US forces to defend Japan should Japan come under attack.[21] However, as left-wing protests in Japan remained a major concern to both Japanese and American leaders alike, the treaty explicitly allowed US military forces based in Japan put down “internal riots and disturbances” in Japan. In addition, in mid-1952, the National Police Reserve was expanded to 110,000 men and named the “National Safety Forces.” Along with it, the Coastal Safety Force was moved to the National Safety Agency to start a de facto navy.

Meanwhile, the Japanese government began a long and ongoing process of gradually reinterpreting Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution to allow greater and greater military capabilities, under the interpretation that Article 9 disallowed offensive warmaking capabilities but did not necessarily deny the nation the inherent right to self-defense. These reinterpretations were avidly encouraged by the government of the United States, which hoped that by remilitarizing Japan would be able to take up more of the burden for its own self-defense. This reinterpretation of Article 9 cleared the way for the creation of a Defense Agency and the transformation of the National Security Force into a “Self-Defense Force” that would be a military in all but name.

On 1 July 1954, the National Security Board was reorganized as the Defense Agency, and the National Security Force was reorganized afterwards as the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (de facto post-war Japanese Army), the Coastal Safety Force was reorganized as the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (de facto post-war Japanese Navy),[18][19] and the Japan Air Self-Defense Force (de facto post-war Japanese Air Force) was established as a new branch of JSDF. General Keizō Hayashi was appointed the first Chairman of the Joint Staff Council—professional head of the three branches. The enabling legislation for this was the 1954 Self-Defense Forces Act [ja] (Act No. 165 of 1954).

The Far East Air Force, U.S. Air Force, announced on 6 January 1955 that 85 aircraft would be turned over to the fledgling Japanese air force on about 15 January, the first equipment of the new force.

On 19 January 1960, the United States and Japan signed a revised version of the US-Japan Security Treaty which corrected the unequal status of Japan in the 1951 treaty by adding mutual defense obligations and which remains in force today. The U.S. is required to give prior notice to Japan of any mobilization of US forces based in Japan. The US is also prohibited from exerting any power on domestic issues within Japan. The treaty obligates Japan and the United States to assist each other if there’s an armed attack in territories administered by Japan. Because it states that any attack against Japan or the United States in Japanese territory would be dangerous to each country’s peace and safety, the revised treaty requires Japan and the United States to maintain capacities to resist common armed attacks; thus, it explains the need for US military bases in Japan. This had the effect of establishing a military alliance between Japan and the United States. The revised treaty has never been amended since 1960, and thus has lasted longer in its original form than any other alliance between two great powers since the Peace of Westphalia treaties in 1648.

Although possession of nuclear weapons is not explicitly forbidden in the constitution, Japan does not own any. The Atomic Energy Basic Law of 1956 limits research, development, and use of nuclear power to peaceful uses only. Beginning in 1956, national policy embodied non-nuclear principles that forbade the nation from possessing or manufacturing nuclear weapons, or allowing them to be introduced into its territories. In 1976, Japan ratified the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (adopted by the United Nations Security Council in 1968) and reiterated its intention never to “develop, use, or allow the transportation of nuclear weapons through its territory”; nonetheless, because of its advanced technological capabilities and large number of operating nuclear power plants, Japan is considered “nuclear capable”, i.e., it could develop usable nuclear weapons within one year if the political situation changes significantly. Thus, many analysts consider Japan a de facto nuclear state. Japan is often said to be a “screwdriver’s turn” away from possessing nuclear weapons, or possessing a “bomb in the basement”.

Fast Shipping with Professional Packaging

Thanks to our longstanding association with UPS FedEx DHL, and other major international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff is expertly trained and will wrap your products according to our exact and precise specifications. Prior to shipping, your goods will be thoroughly examined and securely secured. We ship to thousands clients each day across multiple countries. This shows how we're dedicated to be the largest retailer on the internet. Warehouses and distribution centres can be located throughout Europe as well as the USA.

Note: Orders with more than one item will be assigned a processing date depending on the item.

Before shipping before shipping, we'll conduct a thorough inspection of the items you have ordered. Today, the majority of orders will be delivered within 48 hours. The delivery time will be between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is dynamic and we cannot completely manage it because multiple stakeholders are involved, including our factory and warehouse. So the actual stock may alter at any time. It's possible that you may not receive your order once the order has been made.

Our policy is valid for a period of 30 days. If you don't receive the product within 30 days, we are not able to issue a refund or an exchange.

You can only return an item if it is unused and in the same state as the day you received it. You must have the item in its original packaging.

Related products

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Angolan Rebel 1970s era 60mm Inert Display Mortar from Angolan Civil War Original Items

Uncategorized

Armored Burgonet Helmet & Polearm from Scottish Castle Leith Hall Circa 1700 Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Band of Brothers ORIGINAL GERMAN WWII Le. F.H. 18 10.5cm ARTILLERY PIECE Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Australian WWII Owen MK1 Machine Carbine SMG Custom Fabricated Replica with Sling Original Items

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Armoured Fighting Vehicles of the World: AFVs of World War One (Hardcover Book) New Made Items

Uncategorized